Good Friday

John Masefield, best known for his poem beginning “I must to down to the sea again,” first came to the public’s attention with The Everlasting Mercy (1911), a long narrative poem about a problematic rural character who has a religious awakening. In observance of Good Friday, I cite several passages from the ending of the poem.

According to blogger Arthur Kay, Everlasting Mercy

shocked many with its frankness of language and subject, with its use of the vernacular and a depiction of English country life that sometimes strayed far from the charming scenes we associate with, say, the paintings of Arnold Constable. The poem begins with a grueling boxing bout, a grudge match that fits its rural background and setting quite realistically.

Saul Kane’s redemption begins when a barmaid speaks to him about Christ:

“Saul Kane,” she said, “when next you drink,

Do me the gentleness to think

That every drop of drink accursed

Makes Christ within you die of thirst,

That every dirty word you say

Is one more flint upon his way,

Another thorn about His head,

Another mock by where He tread,

Another nail, another cross.

All that you are is that Christ’s loss.”

The clock run down and struck a chime

And Mrs. Si said, “Closing time.”

The closing of the tavern door brings to Saul’s mind the image of Christ knocking at our door—think of William Holman Hunt’s famous painting “The Light of the World”–and he suddenly feels the urge to open his heart:

The wet was pelting on the pane

And something broke inside my brain,

I heard the rain drip from the gutters

And Silas putting up the shutters,

While one by one the drinkers went;

I got a glimpse of what it meant,

How she and I had stood before

In some old town by some old door

Waiting intent while someone knocked

Before the door for ever locked…

And:

I did not think, I did not strive,

The deep peace burnt my me alive;

The bolted door had broken in,

I knew that I had done with sin.

I knew that Christ had given me birth

To brother all the souls on earth,

And every bird and every beast

Should share the crumbs broke at the feast.

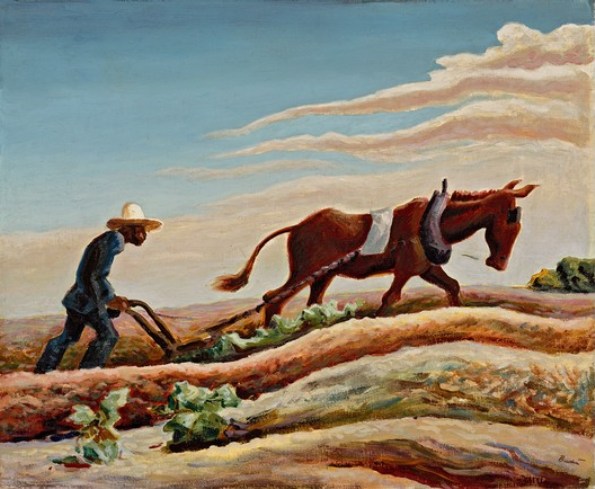

The next day, when Saul is out plowing, he kneel down to God and offers up a magnificent prayer. The fertility imagery reminds me of other writers writing at the time, such as Thomas Hardy and D. H. Lawrence:

I kneeled there in the muddy fallow,

I knew that Christ was there with Callow,

That Christ was standing there with me,

That Christ had taught me what to be,

That I should plough, and as I ploughed

My Savior Christ would sing aloud,

And as I drove the clods apart

Christ would be ploughing in my heart,

Through rest-harrow and bitter roots,

Through all my bad life’s rotten fruits.

O Christ who holds the open gate,

O Christ who drives the furrow straight,

O Christ, the plough, O Christ, the laughter

Of holy white birds flying after,

Lo, all my heart’s field red and torn,

And Thou wilt bring the young green corn,

The young green corn divinely springing,

The young green corn forever singing;

And when the field is fresh and fair

Thy blessèd feet shall glitter there,

And we will walk the weeded field,

And tell the holden harvests’s yield,

The corn that makes the holy bread

By which the soul of man is fed,

The holy bread, the food unpriced,

Thy everlasting mercy, Christ.

May Christ plough our hearts so that young green corn springs forth.