Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

Today is the birthday of conservative satirist Hilaire Belloc, which gives me an excuse for sharing one of his Cautionary Verses for Children. When I was a child, I loved and memorized many of Belloc’s darkly comic poems, which mocked the didactic verse intended to instruct people my age. Belloc writes about what can happen to children who stray from their nannies (get eaten by lions), tell lies (are burned in house fires), slam doors (die), eat pieces of string (again, die) or play with loaded guns (get scolded by their parents).

Belloc wrote in the spirit of Lewis Carroll, who also mocked heavy-handed didactic poetry. “How Doth the Little Crocodile,” for instance, is a send up of Isaac Watts’s “How Doth the Little Busy Bee,” which has such passages as the following:

In works of labor or of skill,

I would be busy too;

For Satan finds some mischief still

For idle hands to do.

Lewis writes:

How doth the little crocodile

Improve his shining tail

And pour the waters of the Nile

On every golden scale!

How cheerfully he seems to grin,

How neatly spreads his claws,

And welcomes little fishes in

With gently smiling jaws!

Alice is often an inadvertent rebel against the adult world, one who tries to follow—but in the process accidentally mocks or subverts—its rules. Sometimes these rules are capricious, at other times so self-evident that they shouldn’t need explaining. For instance, when Alice encounters a bottle that says, “Drink me,” she hesitates:

It was all very well to say “Drink me,” but the wise little Alice was not going to do that in a hurry. “No, I’ll look first,” she said, “and see whether it’s marked ‘poison’ or not”; for she had read several nice little histories about children who had got burnt, and eaten up by wild beasts and other unpleasant things, all because they would not remember the simple rules their friends had taught them: such as, that a red-hot poker will burn you if you hold it too long; and that if you cut your finger very deeply with a knife, it usually bleeds; and she had never forgotten that, if you drink much from a bottle marked “poison,” it is almost certain to disagree with you, sooner or later.

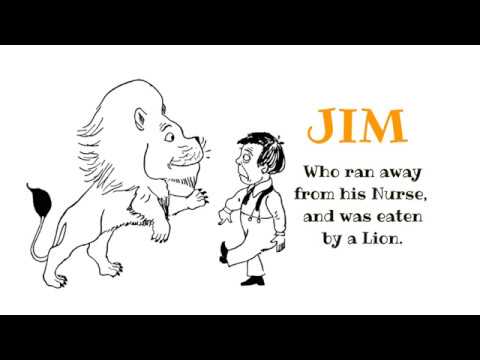

In Cautionary Verses, Belloc comes up with his own “nice little histories.” One of my favorites is “Jim, Who ran away from his Nurse, and was eaten by a Lion”:

There was a Boy whose name was Jim;

His Friends were very good to him.

They gave him Tea, and Cakes, and Jam,

And slices of delicious Ham,

And Chocolate with pink inside

And little Tricycles to ride,

And read him Stories through and through,

And even took him to the Zoo—

But there it was the dreadful Fate

Befell him, which I now relate.

You know—or at least you ought to know,

For I have often told you so—

That Children never are allowed

To leave their Nurses in a Crowd;

Now this was Jim’s especial Foible,

He ran away when he was able,

And on this inauspicious day

He slipped his hand and ran away!

He hadn’t gone a yard when—Bang!

With open Jaws, a lion sprang,

And hungrily began to eat

The Boy: beginning at his feet.

Now, just imagine how it feels

When first your toes and then your heels,

And then by gradual degrees,

Your shins and ankles, calves and knees,

Are slowly eaten, bit by bit.

No wonder Jim detested it!

No wonder that he shouted “Hi!”

The Honest Keeper heard his cry,

Though very fat he almost ran

To help the little gentleman.

“Ponto!” he ordered as he came

(For Ponto was the Lion’s name),

“Ponto!” he cried, with angry Frown,

“Let go, Sir! Down, Sir! Put it down!”

The Lion made a sudden stop,

He let the Dainty Morsel drop,

And slunk reluctant to his Cage,

Snarling with Disappointed Rage.

But when he bent him over Jim,

The Honest Keeper’s Eyes were dim.

The Lion having reached his Head,

The Miserable Boy was dead!

When Nurse informed his Parents, they

Were more Concerned than I can say:—

His Mother, as She dried her eyes,

Said, “Well—it gives me no surprise,

He would not do as he was told!”

His Father, who was self-controlled,

Bade all the children round attend

To James’s miserable end,

And always keep a-hold of Nurse

For fear of finding something worse.

I love how the “self-controlled” father instantly finds a way to turn the tragedy into a moral lesson.

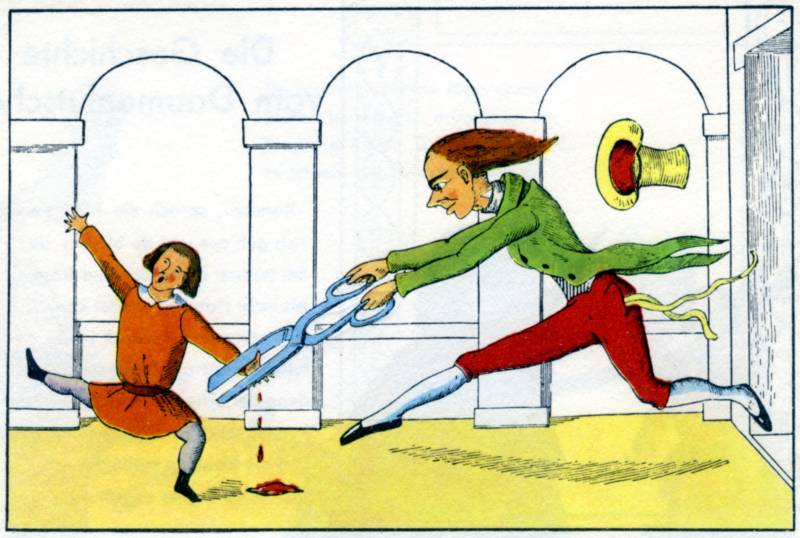

Although I’ve associated Belloc with Lewis, there’s another influence that may be more direct. The 1845 children’s classid Der Struwwelpeter (“Shock-Headed Peter”), written by German author Heinrich Hoffmann, terrified me as a child when its images of a scissor man who cuts off the thumbs of children who continuous sucked them or a girl who burns herself up while playing with matches. (Only her cat is upset.) Although his stories are over the top, Hoffman appears to be serious, writing with the design of terrifying children into submission.

It may be that the poem about thumb sucking is actually a warning against masturbation. Whatever the case, the images of the scissor man chasing the little boy haunted my childhood dreams.

And it’s worth reflecting on the presence of sadism, not only in Der Struwwelpeter and Cautionary Verses, but also in Lewis Carroll and in one of Belloc’s most famous successors, Roald Dahl. Terrible things happen to characters in all of these supposedly comic works for children. In Alice, cats eat mice and birds (so Alice informs a collection of mice and birds), a queen orders beheadings, and the walrus and the carpenter devour a group of oysters they have invited to the beach for a friendly walk and talk. In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, one child blows up like giant blueberry while another falls into a river of chocolate. And of course there’s headmistress Miss Trunchbull in Matilda, who imprisons children in “the chokey” and throws them out of windows.

Rather than turn away in horror, however, children—or at any rate, children who are like I was—are fascinated. They understand such stories and poets are comically satiric, which is one way to handle the conflicting emotions they are starting to have as they learn about violence and death in the world.

In fact, the sadistic thrill they get from bad things happening to literary kids is a way of inoculating themselves. As Hobbes famously theorized, we laugh to proclaim our superiority over those who have some defect or weakness, the weakness in this case being child vulnerability. Children are (in part) Hobbesian creatures, driven by self-interest, and in Belloc they get to relish the demise of children who are both them and not them. If others suffer, maybe we’ll escape.

Of course, when children encounter non-comic versions of child victims, they often sober up. Melodrama tugs at the heart and helps develop empathy. But one must go turn to other kinds of children’s lit to get that. One won’t find it in Belloc.