Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951 at gmail dot com and I will send it/them to you. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

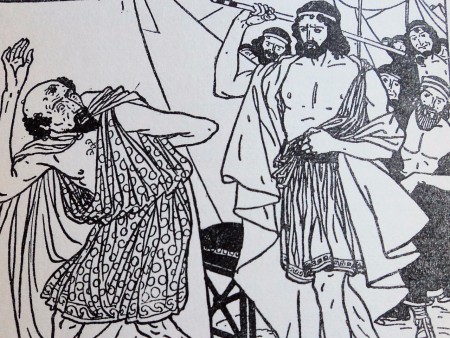

Yesterday I wrote about how, in the first book of The Iliad, Homer delivers a masterclass in leadership. Today I explore a more chilling topic raised by author: how those in power use a combination of mockery, threats, and actual violence to maintain control. It involves an incident that troubled me as a child and that I still find deeply disturbing.

Yesterday, I mentioned how Odysseus salvages a situation that supreme commander Agamemnon has botched. Thinking that he can use reverse psychology on the troops, Agamemnon has suggested they shamefully abandon the war effort and sail for home. Instead of feeling ashamed, however, they leap at the chance and head for their ships. It takes everything Odysseus can do to round them up and bring them back to a council of war.

In that council we encounter Thersites, a man infamous for both his looks (he is bandy-legged, lame in one foot, and “the ugliest man who came beneath Ilion”) and his abusive tongue. Homer describes him as one

who knew within his head many words, but disorderly;

vain, and without decency, to quarrel with the princes

with any word he thought might be amusing to the Argives.

(trans. Richmond Lattimore)

Thersites does not only speak for himself in his subsequent words, however, but voices the resentment that has been building up amongst the troops against Agamemnon and that has been given voice by Achilles. In doing so, he repeats some of the same accusations that we have just heard from that warrior. Achilles has called Agamemnon “the greediest of all men” and one who, while leaving the fighting to others, reserves the greatest part of the booty for himself. Thersites repeats the charge as he makes the case for returning home:

Son of Atreus, what thing further do you want, or find fault with

now? Your shelters are filled with bronze, there are plenty of the choicest

women for you within your shelter, whom we Achaians

give to you first of all whenever we capture some stronghold.

Or is it still more gold you will be wanting, that some son

of the Trojans, breakers of horses, brings as ransom out of Ilion,

one that I, or some other Achaian, capture and bring in?

Is it some young woman to lie with in love and keep her

all to yourself apart from the others? It is not right for

you, their leader, to lead in sorrow the sons of the Achaians.

My good fools, poor abuses, you women, not men, of Achaia,

let us go back home in our ships, and leave this man here

by himself in Troy to mull his prizes of honor

that he may find out whether or not we others are helping him.

At this point in the story, the future of the Greek expedition hangs in the balance. Odysseus saves the day by astutely combining scornful rhetoric with strategic violence. Tactics that could not be used against Achilles can be used against Thersites, who becomes a proxy for the Greek hero. Grabbing Agamemnon’s scepter, symbol of authority, Odysseus begins by diminishing Thersites with his words:

Fluent orator though you be, Thersites, your words are

ill-considered. Stop, nor stand up alone against princes.

Out of all those who came beneath Ilion with Atreides

I assert there is no worse man than you are. Therefore

you shall not lift up your mouth to argue with princes,

cast reproaches into their teeth, nor sustain the homegoing.

We do not even know clearly how these things will be accomplished,

whether we sons of the Achaians shall win home well or badly;

yet you sit here throwing abuse at Agamemnon,

Atreus’ son, the shepherd of the people, because the Danaan

fighters give him much. You argue nothing but scandal.

Then come the threats:

And this also will tell you, and it will be a thing accomplished.

If once more I find you playing the fool, as you are now,

nevermore let the head of Odysseus sit on his shoulders,

let me nevermore be called Telemachos’ father,

if I do not take you and strip away your personal clothing,

your mantle and your tunic that cover over your nakedness,

and send you thus bare and howling back to the fast ships,

whipping you out of the assembly place with the strokes of indignity.

Finally Odysseus backs up the threats with action, turning the scepter—meant to peacefully convey authority—into a weapon. In doing so, he reveals the hard power that always lurks behind soft power:

So he spoke and dashed the scepter against his back and

shoulders, and he doubled over, and a round tear dropped from him,

and a bloody welt stood up between his shoulders under

the golden sceptre’s stroke, and he sat down again, frightened,

in pain, and looking helplessly about wiped off the tear-drops.

This show of force impresses the troops. While their own lives would be better if they listened to Thersites—they would return home without further fighting–Odysseus has turned the man into a pathetic object of derision, something he could not have done with Achilles. Thersites here functions as a scapegoat: when the troops proceed to laugh at him, they are imagining themselves as princes, not as common soldiers. Odysseus’s move is right out of the authoritarian playbook:

Sorry though the men were they laughed over him happily,

and thus they would speak to each other, each looking at the man next him:

‘Come now: Odysseus has done excellent things by thousands,

bringing forward good counsels and ordering armed encounters;

but now this is far the best thing he ever has accomplished

among the Argives, to keep this thrower of words, this braggart

out of assembly. Never again will his proud heart stir him

up, to wrangle with the princes in words of revilement.’

Their laughter is of the sort described by Thomas Hobbes in his classic work Leviathan. As the 17th century political philosopher sees it, laughter is a means of asserting your authority in a world defined by the struggle for power. We laugh at others because it makes us feel superior to them (“sudden glory”) while hiding our own imperfections:

Sudden glory, is the passion which maketh those Grimaces called LAUGHTER; and is caused either by some sudden act of their own, that pleaseth them; or by the apprehension of some deformed thing in another, by comparison whereof they suddenly applaud themselves. And it is incident most to them, that are conscious of the fewest abilities in themselves; who are forced to keep themselves in their own favor, by observing the imperfections of other men. And therefore much Laughter at the defects of others is a sign of Pusillanimity.

Through bullying Thersites, who is in fact a “deformed thing,” Odysseus rallies the troops to his side. Although they were fleeing for their ships only moments before, now they are prepared to charge into battle:

So he spoke, and the Argives shouted aloud, and about them

the ships echoed terribly to the roaring Achaians

as they cried out applause to the word of godlike Odysseus.

Agamemnon, this time effectively, follows up Odysseus’s call, eliciting a response that is compared to waves crashing against a cliff:

So he spoke, and the Argives shouted aloud, as surf crashing

Against a sheerness, driven by the south wind descending,

some cliff out-jutting, left never alone by the waves from

all the winds that blow, as they rise one place and another.

So how does an authoritarian rally the troops? By scapegoating marginalized persons through the use of insults, threats of violence, or even actual violence. If you do it well, your audience will ignore their own concerns and follow you anywhere.

Further thought: Political scientist John Stoehr, whose columns I follow on The Editorial Board, notes that the tactics used by Odysseus are not limited to demagogues but can be seen at work in society as a whole. Whites retain control in an increasingly diverse society by appearing moderate while relying on a police force that functions like an occupying army. (Whites don’t see the police this way, of course, but others do.) As Stoehr puts it in a recent column:

Occupying armies—in order to keep the peace, uphold the law and preserve the order—periodically send a message to the local population that disorder will not be tolerated. To that end, they will seek out and destroy someone, usually the weak, with a spectacular display of violence.

That’s what happened last week in Huntington, California. The city’s occupying army made an example of a Black man with no legs. (They said he was armed with a knife.) They shot to death Anthony Lowe, Jr., as he ran from them in terror on his tumps. Who’s in charge. The occupying army.

White power elites and police departments have also countenanced, if not outwardly endorsed, extralegal violence, such as lynchings in the Jim Crow south and routine police violence today. Certain members of the GOP won’t even allow the gun violence of current White terrorists to be labeled terrorism and look for ways to minimize their actions. Their main problem with the recorded killings of George Floyd and Tyre Nichols is that they threaten to expose the workings of the system.

That system can be seen clearly in Odysseus’s handling of Thersites.

In Stoehr’s view, America’s best hope lies in “reasonable White people” rejecting the constituent elements of that system–White supremacy, White fear, White privilege and sense of entitlement–and instead making common cause with people of color.