Friday

I love retirement but regret how it has separated me from the literary insights of students. Over half of what I know about literature I have either learned directly from them or have arrived at through class preparation. Fortunately, Sewanee College has asked me to teach a “Composition and Literature” class and, as expected, I’m learning new things.

I recently taught Mary Oliver’s American Primitive and finally understood three poems that have always eluded me. I now have new insights into how an introvert experiences life.

Oliver was a private person but could feel trapped inside herself. She understood that, frightening though it can be to venture outside one’s comfort zone, great rewards await those who do so. In a number of her poems one sees a tug of war between wanting to hunker down and wanting to venture out.

My student Alexander Knight alerted me to this particular dynamic in his essay on her poem “Flying.” Alexander is a self-described extrovert but he has several very introverted friends. He used the poem to understand them better.

In “Flying” the speaker is so struck by the beauty of a stranger on an airplane that she feels compelled to get up and lightly bump against him:

Sometimes,

on a plane,

you see a stranger.

He is so beautiful!

His nose

Going down in the

old Greek way,

or his smile

a wild Mexican fiesta.

You want to say:

do you know how beautiful you are?

You leap up

into the aisle,

you can’t let him go

until he has touched you

shyly, until you have rubbed him,

oh, lightly,

like a coin

you find on the earth somewhere

shining and unexpected and,

without thinking,

reach for. You stand there

shaken

by the strangeness,

the splash of his touch.

When he’s gone

you stare like an animal into

the blinding clouds

with the snapped chain of your life,

the life you know:

the deeply affectionate earth,

the familiar landscapes

slowly turning

thousands of feet below.

If he had been Oliver, Alexander said, he would have introduced himself. Yet he realized his friends, like Oliver, wouldn’t do so in a thousand years. Although this means they lose out on certain experiences, it also means what experiences they do have are particularly intense.

In this poem, a mere “splash of his touch” sends the speaker spiraling away from earth. The chain that holds her to life as been snapped and she feels as though she is flying.

Once Alexander pointed out this dynamic, I found it in poem after poem. In “Lightning,” for instance, Oliver describes a back and forth between fearfully remaining isolated and excitedly rushing out like blazing lightning:

…it was hard to tell

fear from excitement:

how sensual

the lightning’s

poured stroke! and still,

what a fire and a risk!

As always the body

wants to hide,

wants to flow toward it - strives

to balance while

fear shouts,

excitement shouts, back

and forth - each

bolt a burning river

tearing like escape through the dark

field of the other.

This other—other people—feels risky, but the passionate fire makes it worthwhile.

In “Bobcat,” one finds the same dynamic. The poet is driving through dark roads at night when suddenly a bobcat leaps into view, causing hearts to thud and stop:

What should we say

is the truth of the world?

The miles alone

in

the pinched dark?

or

the push of the promise?

or the wound of delight?

“Wound of delight,” like the tearing lightning, captures the experience for an introvert: the contact with the external world hurts but is exhilarating.

The poem “John Chapman” shows what can happen with an introvert is wounded too much. Johnny Appleseed, once deceived by a woman, seems most comfortable in the company of animals. Oliver notes that he

thought little,

on a rainy night,

of sharing the shelter of a hollow long touching

flesh with any creatures there: snakes,

racoon possibly, or some great slab of bear.

Yet the hermit finds another way of sharing himself with the world: he gives it apple trees, “lovely/ as young girls,” and to this day “you can still find sign of him”:

In spring, in Ohio,

in the forests that are left you can still find

sign of him: patches

of cold white fire.

Even when introverts have their worst fears realized, Oliver says they still have a decision to make:

to die,

or to live, to go on

caring about something.

In other words, even wounded introverts can find their own way of sharing themselves with us. In the introverted Oliver’s case, her patches of cold white fire were her poems.

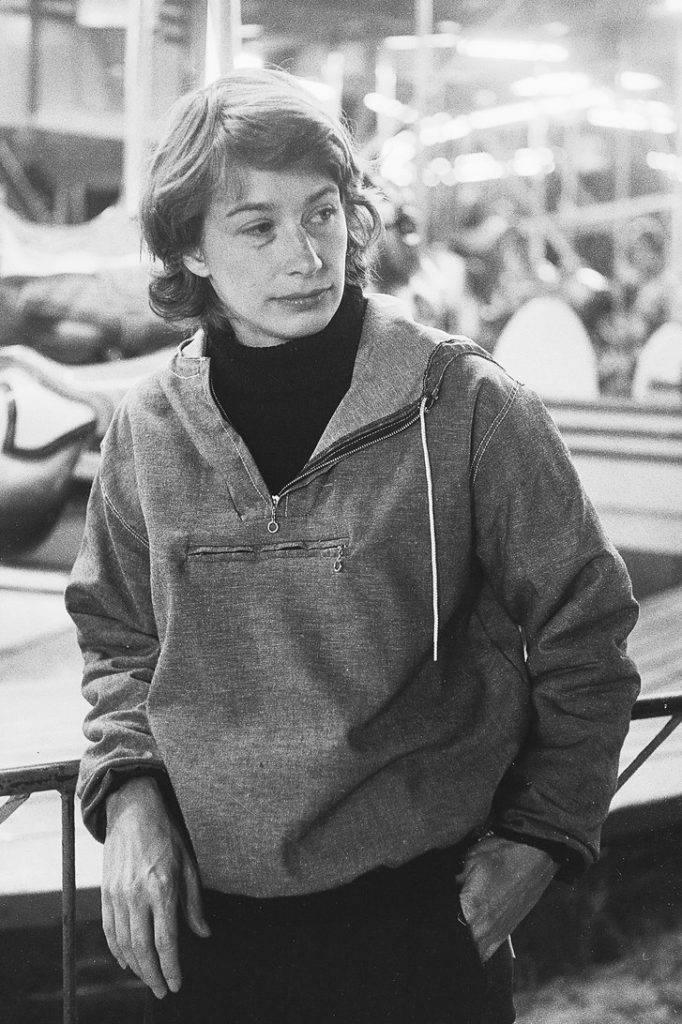

Personal memory: I had the honor of dining with Oliver when she made a rare campus visit, in this case to visit her friend Lucille Clifton. Although she was quiet and withdrawn, I was able to share with her an Oscar Wilde passage that she appreciated: “Ignorance is like a rare fruit. Touch it and the bloom is gone.”