Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

I’m a newcomer to the fiction of Kate Atkinson, whose novels I’ve just discovered. Among the pleasures I get from reading this author of period pieces and unconventional crime novels is her use of literary allusions. There’s a certain satisfaction in being able to identify the passages she sprinkles liberally through her books.

She does something special with these allusions in A God in Ruins, a sequel of sorts to Life after Life. In both novels she follows the fortunes of the Todd family, including favorite child Teddy. Teddy grows up to become a revered bomber pilot during World War II, miraculously surviving when his plane is shot down over Berlin. He is interned in a German prisoner-of-war camp, then returns to live a quiet life as nature writer and reporter for a rural newspaper. In the end, he relives his harrowing war experiences as he is expiring of old age in a nursing home.

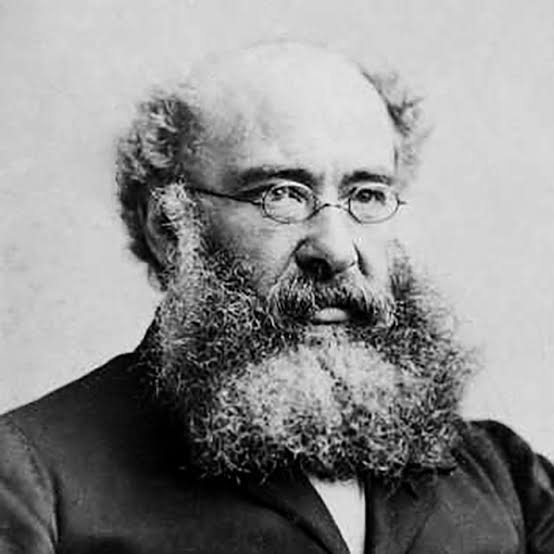

What I find special in God in Ruins is how Atkinson uses past literature to capture Teddy’s death. There is, first of all, her call out to Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope, which first Teddy and then his granddaughter turn to in his last days and hours. Then she begins citing fragments from many poems, using them as T.S. Eliot uses scraps of literature to make sense of a senseless world (and what seems more senseless to us than our death?). “These fragments I have shored against my ruins,” Eliot writes in Waste Land.

First to Trollope, which Teddy’s beloved granddaughter Bertie reads to him in his final hours. Julia and I did the same with my mother. While we didn’t read Trollope, we perhaps should have given that he was my mother’s favorite novelist.

If Atkinson gives prominence to Trollope in God in Ruins, it’s perhaps because his depictions of multigenerational families in rural England, who are sometimes described lovingly and sometimes satirized, provide a model for her own writing. The first reference to Trollope occurs when Teddy learns that he is being interviewed by “the warden” of a nursing home he doesn’t want to retire to, which prompts him to think of The Warden, the first of the Chronicles of Barsetshire series. While warden Septimus Harding, a lovely character, bears no resemblance to the warden in the nursing home, his decency and kindness have a lot in common with Teddy.

Later in God in Ruins, we find Teddy turning to Trollope after a bout of pneumonia. His daughter Viola discovers “that he’d been reading the first chapter of Barchester Towers [the second book in the series] over and over again, looping round and coming to it fresh each time.”

Is it sad or is it wonderful that the book is constantly refreshed?

Then, in the final hours of Teddy’s life, we learn that granddaughter Bertie

had brought a copy of the Last Chronicle of Barset with her and sat by Teddy’s bedside reading to him. She knew it was one of his favorite books and she supposed it didn’t matter much whether or not he could understand the words because it might be soothing for him to read the familiar rhythms of Trollope’s prose.

Could Atkinson be thinking of the passage in Last Chronicle when Harding’s daughters are sitting by his own deathbed:

During the whole of the morning Mrs. Arabin and Mrs. Grantly were with their father, and during the greater part of the day there was absolute silence in the room. He seemed to sleep; and they, though they knew that in truth he was not sleeping, feared to disturb him by a word.

And a little later:

“It is so sweet to have you both here,” he said, when he had been lying silent for nearly an hour after the child had gone. Then they got up, and came and stood close to him. “There is nothing left for me to wish, my dears;—nothing”…

There was no violence of sorrow in the house that night; but there were aching hearts, and one heart so sore that it seemed that no cure for its anguish could ever reach it. “He has always been with me,” Mrs. Arabin said to her husband, as he strove to console her. “It was not that I loved him better than Susan, but I have felt so much more of his loving tenderness. The sweetness of his voice has been in my ears almost daily since I was born.”

When my mother was dying, she didn’t share any last words, but I found myself thinking about all that she was, all that she had done, and all she had meant to those who loved her. And I thought of her deep love of literature, which gave her special resonance in how she saw the world and interacted with it.

I’ll have more on how Atkinson uses literature to negotiate the byways of death in tomorrow’s post.