Thursday

Listening to Dickens’s handling of the orphan boy Jo in Bleak House during our trip to Maine, I can’t help but apply it to the way that we treat immigrants at our borders or the homeless at home. We want them “out of sight, out of mind” and deputize law enforcement to make this happen.

It’s a centuries-old problem, as I learned when I took a Tudor England history class in college and learned about “the wandering poor.” We’re going to see much more wandering in the decades to come as extreme climate events disrupt whole populations while autocrats indulge in ruinous foreign wars and domestic crackdowns. Dickens gives us a close-up picture of one such person affected.

Jo is a poor and illiterate boy who sweeps the street every day for whatever pennies people will give him and then goes home to a wretched crawlspace in Tom-All-Alone’s, the poorest part of London. Though his actions hurt no one, those responsible for “public decency” insist that he “move on”:

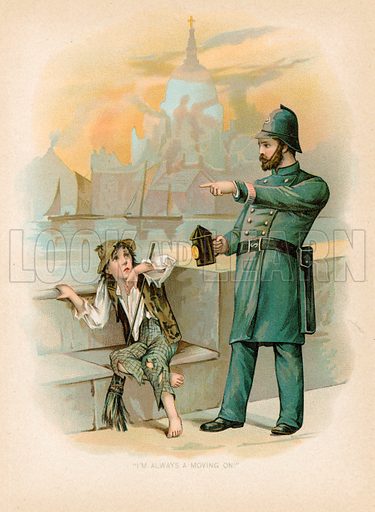

Mr. Snagsby descends and finds the two ‘prentices intently contemplating a police constable, who holds a ragged boy by the arm.

“Why, bless my heart,” says Mr. Snagsby, “what’s the matter!”

“This boy,” says the constable, “although he’s repeatedly told to, won’t move on—”

“I’m always a-moving on, sar,” cries the boy, wiping away his grimy tears with his arm. “I’ve always been a-moving and a-moving on, ever since I was born. Where can I possibly move to, sir, more nor I do move!”

“He won’t move on,” says the constable calmly, with a slight professional hitch of his neck involving its better settlement in his stiff stock, “although he has been repeatedly cautioned, and therefore I am obliged to take him into custody. He’s as obstinate a young gonoph [pickpocket or thief] as I know. He WON’T move on.”

“Oh, my eye! Where can I move to!” cries the boy, clutching quite desperately at his hair and beating his bare feet upon the floor of Mr. Snagsby’s passage.

“Don’t you come none of that or I shall make blessed short work of you!” says the constable, giving him a passionless shake. “My instructions are that you are to move on. I have told you so five hundred times.”

“But where?” cries the boy.

“Well! Really, constable, you know,” says Mr. Snagsby wistfully, and coughing behind his hand his cough of great perplexity and doubt, “really, that does seem a question. Where, you know?”

“My instructions don’t go to that,” replies the constable. “My instructions are that this boy is to move on.”

Dickens at this point intervenes to deliver one of his characteristic lectures, lambasting Parliament for its failure to devise social solutions:

Do you hear, Jo? It is nothing to you or to anyone else that the great lights of the parliamentary sky have failed for some few years in this business to set you the example of moving on. The one grand recipe remains for you—the profound philosophical prescription—the be-all and the end-all of your strange existence upon earth. Move on!

Then Dickens makes a contrast between “move on” and “move off.” I think (but am not sure) that “moving off” would require some kind of policy prescription—as in “move off to ____.” As Dickens notes,

You are by no means to move off, Jo, for the great lights can’t at all agree about that. Move on!

From this perspective, I suppose it is to his credit that Donald Trump yesterday proposed a concrete solution, even though one that calls for forcible removal—which is to say, a crime against humanity. As Yahoo News reports, his own phrase is “move out”:

Donald Trump said homeless people should be forcibly removed from urban centers and moved to purpose-built camps on the outskirts of major United States cities during a speech at the America First Policy Institute’s summit in Washington this week.

“You have to move people out,” Mr Trump told an audience during his keynote address at Tuesday’s summit.

As Trump sees it, the homeless should be moved out—or off—to “large parcels of inexpensive land in the outer reaches of the city.” And then, to make his idea slightly more palatable, he recommends housing them in “thousands and thousands of high-quality tents.”

Given GOP parsimony when it comes to the poor, I wouldn’t bet on high quality anything. The idea of cleansing our cities by forcibly relocating undesirables to internal refugee or concentration camps, however, is perfectly consistent with authoritarian thinking.

Towards the end of the novel, the constant moving on finally ends in Jo’s death, leading to a Dickensian denunciation, complete with savage sarcasm:

Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, right reverends and wrong reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with heavenly compassion in your hearts. And dying thus around us every day.

But at least in the grave where Jo asks to be buried—next to a poor scrivener who was kind to him—he will be out of sight, out of mind.