A couple of weeks ago there was a dust-up between Donald Trump and Pope Francis when the pope labeled “not Christian” those who talk about building walls but not bridges. (The comment was in response to a question about the wall proposed by Trump.) I’ve written several blog posts about immigrants in the past (see the links at the end of the article) and today delve into what Robinson Crusoe has to contribute to the discussion. Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel, I believe, helps us understand why such “not Christian” behavior is nevertheless attracting rightwing Christians to Trump and also to Ted Cruz, who is equally vociferous on the subject.

First of all, an observation on the pope’s comments. I don’t think he was intervening in American politics but making rather a theological comment. Jesus is unequivocal about what happens to those with stony hearts:

I promise you that any of the sinful things you say or do can be forgiven, no matter how terrible those things are. But if you speak against the Holy Spirit, you can never be forgiven. That sin will be held against you forever.” (Mark 3:28-29)

I see this statement less as a judgment and more as a psychological description. If we turn away from the divine love that is within us, we create a hell for ourselves. Being a Christian means following Christ’s example and opening oneself to God, so the pope is merely stating what is in his mind a theological fact.

To bring Robinson Crusoe into the conversation requires some background explaining so bear with me. The key works here are Max Weber’s Protestantism and the Spirit of Capitalism and R. H. Tawney’s Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. Both argue that Calvinist fears of damnation spurred capitalist achievement since Puritans felt they had to prove to themselves that they were amongst the elect—which is to say, that they were predestined for heaven rather than for hell. They came to think that worldly success was evidence that they were heading for the good place and therefore had extra incentive to attain that success. This isn’t logical since Calvinists don’t believe that you can increase your chances of being amongst the elect. It makes psychological sense, however, since you desperately want reassurance and therefore are apt to tilt what you see as the indicators.

One sees a fear of damnation driving Robinson Crusoe. Crusoe has disobeyed his father by running off to sea and he is haunted by guilt. To prove to this internal father that he is a good son, he works incessantly, trying to make every minute count. No matter how much Crusoe builds, however, it is never enough. He must always create more to quiet his internal doubts.

Our current Protestant work ethic is not as overt as the Calvinism of the 18th and 19th centuries—one doesn’t hear a lot of talk about predestination—but the sense that one is somehow deficient if one is a “loser” still resides. Prosperity theology argues that those who are right with God prosper economically, while those who are poor are somehow offensive to God. Thus you can have ardent capitalists like Trump and Cruz strutting their Christian credentials while advocating the building of various walls to shut out the less fortunate.

Walls are also Crusoe’s specialty. Building them, even when they don’t seem necessary, is a way to quiet his doubts. Rather than provide reassurance, however, the fences increase his sense of vulnerability. Here’s a passage from the earlier post, written in July, 2014:

There is a psychological price paid by those who insist upon absolute borders: the thicker the barrier, the thicker the fear and paranoia. This helps explain why the hysteria of American nativists is swamping the efforts of moderate Republicans to work with Democrats to enact comprehensive immigration reform.

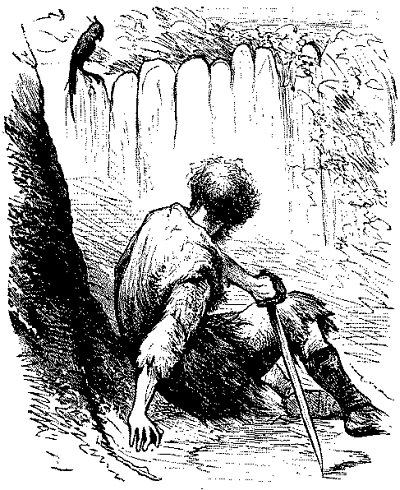

Crusoe engages in incessant labor to build an impregnable fortress for himself—but in an ironic twist that I think shows how walling out the world actually increases feelings of vulnerability, his own security becomes trap.

The trap is symbolized by a cave-in, caused by an earthquake and storm that strike within 24 hours of Crusoe completing his fortress. Crusoe actually has to breach his barrier so that he will not be drowned by a torrential downpour.

Back to rightwing Christian support for Trump and Cruz. These are two politicians who are raising walls between Christians and others, telling their followers that they are victims of immigrant Muslims or repressive secularists and that the wealth that should be theirs is going to undeserving poor and minorities. The thicker the walls they propose, the more the paranoia grows.

It appears not to matter to Trump and Cruz supporters that Deuteronomy 10:18 insists that orphans and widows should receive justice and that we should “show[ ] love to the foreigners living among you and give[ ] them food and clothing,”

Robinson Crusoe is not only about walls, however, and there is an instance where he builds a bridge. Or rather, where he shares a ladder. Again I quote from my earlier post, which includes two contrasting passages from the novel. In the first, Crusoe is fearful of Friday and walls him out. In the second, he realizes he can drop the barriers:

The next day, after I came home to my hutch with him, I began to consider where I should lodge him: and that I might do well for him and yet be perfectly easy myself, I made a little tent for him in the vacant place between my two fortifications, in the inside of the last, and in the outside of the first. As there was a door or entrance there into my cave, I made a formal framed door-case, and a door to it, of boards, and set it up in the passage, a little within the entrance; and, causing the door to open in the inside, I barred it up in the night, taking in my ladders, too; so that Friday could no way come at me in the inside of my innermost wall, without making so much noise in getting over that it must needs awaken me; for my first wall had now a complete roof over it of long poles, covering all my tent, and leaning up to the side of the hill; which was again laid across with smaller sticks, instead of laths, and then thatched over a great thickness with the rice-straw, which was strong, like reeds; and at the hole or place which was left to go in or out by the ladder I had placed a kind of trap-door, which, if it had been attempted on the outside, would not have opened at all, but would have fallen down and made a great noise—as to weapons, I took them all into my side every night.

Eventually he learns that his fears are groundless and he has nothing to worry about—which America might conclude as well if it were to stop obsessing over dark-skinned people:

But I needed none of all this precaution; for never man had a more faithful, loving, sincere servant than Friday was to me: without passions, sullenness, or designs, perfectly obliged and engaged; his very affections were tied to me, like those of a child to a father; and I daresay he would have sacrificed his life to save mine upon any occasion whatsoever—the many testimonies he gave me of this put it out of doubt, and soon convinced me that I needed to use no precautions for my safety on his account.

I concluded the earlier post as follows:

Okay, so this is paternalistic and I’m not holding it up as a model for white-non-white friendships. But I do find it interesting how Crusoe periodically has his cultural assumptions upended. At one point he discovers that Europeans—I have in mind the mutineers who find their way to the island—can be no less savage than the cannibals.

The bigger point is that, when we insist on fences, we become defined by our fears, which threaten to bury us like Crusoe’s earthquake. Whereas when we open ourselves up to the Other, we may find a friend. May all Americans be open to this truth as we deal with the latest Latin American immigrants.

I believe this is what the pope was trying to say.

Previous posts on immigrants

Robinson Crusoe: Walls Entrap Rather Than Protect

Adrienne Rich: The Immigrants Choice

Robert Frost: Fences, Good Neighbors, and Immigration

William Carlos Williams: Caution, Don’t Stereotype Immigrants

A Tolstoy Story about Radical Empathy

Ralph Ellison: Invisible Men (and Women) No Longer

Steinbeck Described Anti-Migrant Protests

Inauguration Poet, Classic Immigrant Story

Grapes of Wrath Fermenting in Alabama