Thursday

Stephen Greenblatt, the world’s preeminent Shakespearean, has weighed in on the Shakespeare-in-the-Park production of Julius Caesar and basically called the complainers wimps. After all, Queen Elizabeth I once faced a similar situation–only in her case someone tried to use a Shakespeare play to actually overthrow her–and shrugged it off.

I posted about the complainers yesterday, but here’s a reminder of what happened. The production has a Donald Trump lookalike playing the role of Caesar and, of course, getting graphically stabbed. The usual suspects raised a hue and cry, and Delta Airlines and Bank of America withdrew their sponsorship. Yesterday, after members of the Congressional Republican baseball team were fired upon, the always classy Donald Trump, Jr. retweeted the message,

Events like today are EXACTLY why we took issue with NY elites glorifying the assassination of our President.

Like others, Greenblatt first points out that the play doesn’t glorify assassination:

And then there is the fact that Julius Caesar is a powerful, sustained demonstration of the risks and consequences of attempting to protect the republic through violence. Brutus and his fellow conspirators assassinate the vulgar, swaggering would-be tyrant to save their country’s freedom, but they wind up paving the way for the tyranny of the cool, uncharismatic, methodical politician Octavius.

Then Greenblatt offers some very useful historical context:

Robust cultures, including corporate cultures, do not panic in the face of theatrical free expression but welcome it. Shakespeare’s contemporaries were wise enough to take heed. Even in a time of intense anxiety and repression, they generally left the theater alone. After all, they understood, the stage is a place where leaders and the public can think through their political conflicts and the ramifications of risky impulses to take action, heroic or otherwise. When one eliminates that space, it isn’t as though the conflicts and impulses disappear — there is simply less opportunity to consider them together in a serious, considered way.

The Elizabethans let plays go on even even though there was a law on the books declaring it high treason, punishable by being drawn and quartered, “to compass or imagine” the ruler’s death. (Think how Trump might make use of that law.) And even though, as Greenblatt points out,

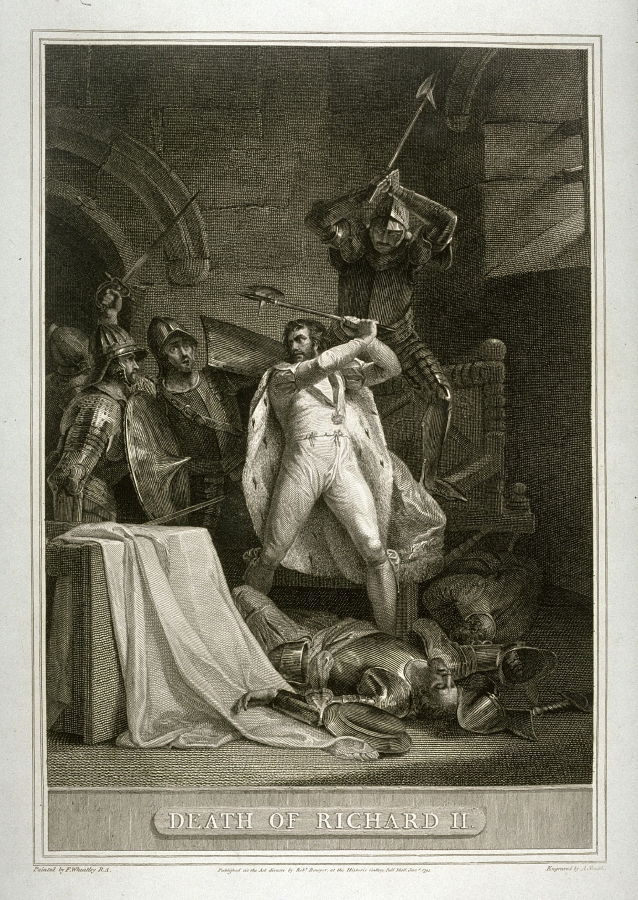

almost all of the tragedies by Shakespeare are precisely about imagining the ruler’s death. “For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground/And tell sad stories of the death of kings,” says his Richard II, shortly before he is himself murdered; “How some have been deposed; some slain in war, …/Some poisoned by their wives; some sleeping killed;/All murdered.”

Greenblatt cites Richard II because the play was in fact used in an attempt to overthrow the monarch (!). On the afternoon before his attempted coup against Elizabeth, the Earl of Essex paid for a special production of Richard II in order to sway potential supporters. Elizabeth even knew that the play was being used for this purpose:

“I am Richard II; know ye not?” asked the exasperated Elizabeth. “This tragedy,” she added hyperbolically, “was forty times played in open streets and houses.”

But here’s the amazing thing. While Elizabeth executed Essex and several of his supporters, she

did nothing to punish Shakespeare or his company. On the contrary, she continued her key support for the theater — more substantial than anything that Delta Air Lines or the Bank of America provide to the Public.

Greenblatt’s advice to our modern day complainers is wise:

Perhaps Elizabeth actually listened to Shakespeare’s play and understood that it was not an incitement to violence but a deeply thoughtful exploration of the tragic dilemmas of political life. And perhaps she understood that the theater is one of those places where it is far more dangerous to police the imagination than to allow it to flourish.

Literature will make you smarter if you truly listen to it. First, however, you have to want to be smart.