Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Tuesday

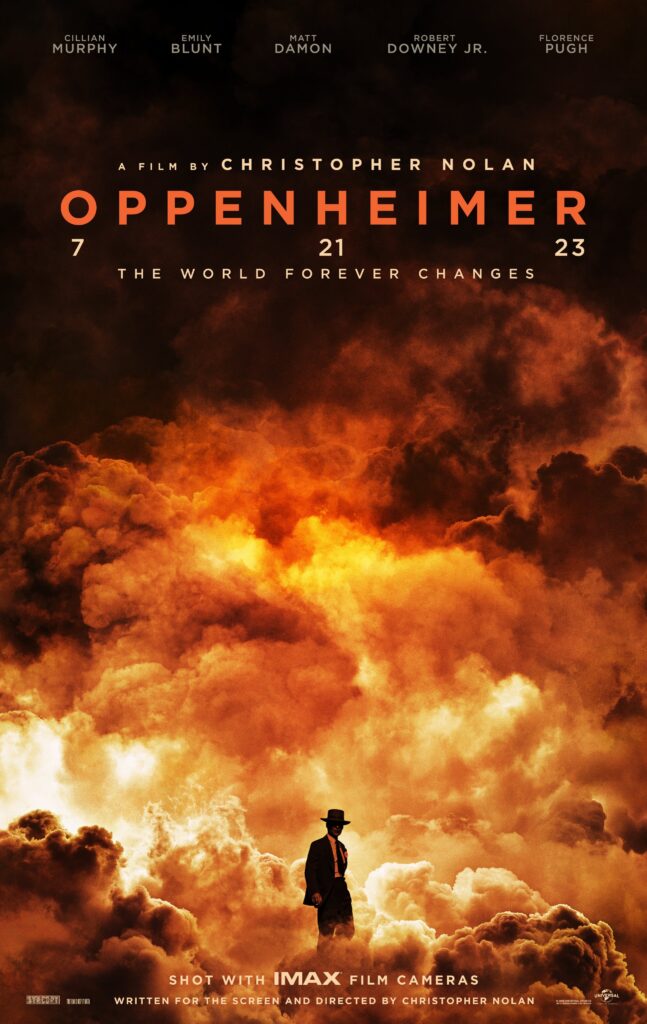

Back in 2010 I blogged on how Robert Oppenheimer was a fan of the devotional poet George Herbert. I had just read a biography co-written by my Carleton classmate Kai Bird, who turned up this fascinating fact. Now that Kai’s book has been turned into a Christopher Nolan biopic, I’ve learned about another 17th century poet that Oppenheimer liked. Apparently, in settling upon “Trinity” as the code name for the detonation of the first atom bomb, the director of the Manhattan Project was alluding to the John Donne sonnet “Batter My Heart, Three-Person’d God.”

[Side note about Kai Bird: When I was news editor of Carleton’s student newspaper, he would send us dispatches about unrest in Pakistan, where he was studying. Running his articles on atrocities directed against what was then East Pakistan, we billed Kai as our “correspondent in Pakistan,” as though we had multiple foreign correspondents.]

In American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Kai and Martin Sherwin relate a story about a dinner party involving Oppenheimer, theologian Reinhold Neibuhr, and diplomat George Kennan, the architect of the Soviet containment doctrine. Discovering that Kennan did not know Herbert’s poetry, Oppenheimer apparently introduced him to “The Pulley.” Here’s the poem:

The Pulley

By George Herbert

When God at first made man,

Having a glass of blessings standing by;

Let us (said he) pour on him all we can:

Let the world’s riches, which dispersed lie,

Contract into a span.

So strength first made a way;

Then beauty flowed, then wisdom, honor, pleasure:

When almost all was out, God made a stay,

Perceiving that alone, of all his treasure,

Rest in the bottom lay.

For if I should (said he)

Bestow this jewel also on my creature,

He would adore my gifts instead of me,

And rest in Nature, not the God of Nature:

So both should losers be.

Yet let him keep the rest,

But keep them with repining restlessness:

Let him be rich and weary, that at least,

If goodness lead him not, yet weariness

May toss him to my breast.

As both biography and film make clear, Oppenheimer was a brilliant and conflicted individual. Along with being one of the world’s leading scientists, he was also a Renaissance man, at one point learning Sanskrit and reading the Bhagavad Gita in the original. (This enabled him, after witnessing the first atomic explosion, to quote Krishna, “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”) He had a restless intellect that never stopped.

That’s why he was drawn to the restless Herbert. “The Pulley” is a poem about what it takes to “pull” us to God, the nature of a pulley being that we must descend to rise. While Herbert appreciates God’s generous gifts to humans, he can’t understand why he has difficulty opening his heart to God. He even seems to blame God for making him this way. Why has God given him a restless mind that obstructs his desire to surrender to the divine? Intellectually he knows what he should do, but he can’t love God with all his heart, soul, strength and mind, as Jesus counseled. I sense that he feels like a bird beating itself against a mental cage.

Herbert laments his restlessness in other poems as well. In “The Collar,” for instance, he describes himself as raving and growing fierce and wild. One can see such restlessness in the Nolan film, which finds powerful images for conveying Oppenheimer’s inner state. While sometimes we see him gazing with wonder at the pulsating universe, at others we see him driven almost mad by the power he sees in exploding stars, where the gravitational pull is so strong that it can swallow light. Sometimes he fears that the chain reaction he is seeking will ignite the atmosphere and end all life on earth.

In Herbert’s case, “The Pulley” ends with consolation. Maybe, the poet figures, he will wear himself out so much that he will fall at last, exhausted, into God’s arms. Maybe then he will find “the peace that passeth all understanding,” to quote from the Anglican liturgy. If he can’t find peace through his strength, beauty, wisdom, and honor, perhaps he will arrive there through fatigue.

The gifted Oppenheimer understood Herbert’s struggle, even if, as a secular Jew, he didn’t embrace the poet’s vision of atonement with God. Fully aware that his own brilliance was not leading him to inner peace, he appreciated Herbert for voicing his condition. Perhaps he was soothed by the poet’s vision of final rest.

One encounters similar restlessness in the poem that led to his “Trinity” designation. In “Sonnet XIV” Donne, an intellectual poet if there ever was one, is despairing that his Reason can’t save his heart from being taken over by irrational dark forces:

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

I, like an usurp’d town to another due,

Labor to admit you, but oh, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend,

But is captiv’d, and proves weak or untrue.

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov’d fain,

But am betroth’d unto your enemy;

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

Oppenheimer may not believe that it is Satan who has captured the citadel of his heart (Donne writes that he is “betroth’d” unto God’s enemy). But the scientist does know that “Reason” is not saving him, meaning that he needs tough love to batter the enemy that is swarming over his defenses. He knows that, to borrow from Bacall’s line to Bogart in the movie The Big Sleep, “Sugar won’t work. It’s been tried.”

One can see the connection he draws between a three-person’d Trinity that batters and the most powerful human-caused explosion the world has ever seen. Did Oppenheimer really desire for the bomb would batter the world with god-like force? Was there some part of him that thrilled when he quoted Krishna’s “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”? Perhaps, momentarily, the answer to both questions is yes. After all, he saw that it would take supreme force, not rational negotiation, to stop the Nazi slaughter of his people. But scientific Reason, of which he was a master and upon which he relied to guide his life, failed to quell his inner turmoil.

I’m not convinced that Oppenheimer is a great film—the director often gets lost in the weeds—but Nolan’s depiction of this turmoil explains why Oppenheimer would have been drawn to 17th century metaphysical poetry. At few times in literary history has Reason been more at war with itself.