Monday

We’re packing up our house to move and I’m feeling overwhelmed by all the stuff we have accumulated over the years. We are disposing of boxes and boxes of bric-a-brac, a word I first encountered when reading Ozma of Oz as a child. L. Frank Baun’s third book in the Oz series captures how we become entrapped by “small articles commonly of ornamental or sentimental value” (Webster’s Dictionary).

In the novel, Oz’s new queen sets off to rescue the princess of Ev and her ten children, who have been sold to the Nome King by Ev’s king in exchange for a long life. The underground monarch turns them all into bric-a-brac and gives Ozma a choice: with eleven guesses she can either identify them or become bric-a-brac herself.

Ozma and her followers proceed to be added to the Nome king’s collection. Fortunately, Billina the hen overhears the king’s color coding system (purple for the Ev family, green for the Oz characters, etc.) and is able to free everyone.

Thematically, Baum may be criticizing early 20th century materialism. The Nome King runs an industrial empire that produces immense wealth, and the end result is rooms filled with bric-a-brac:

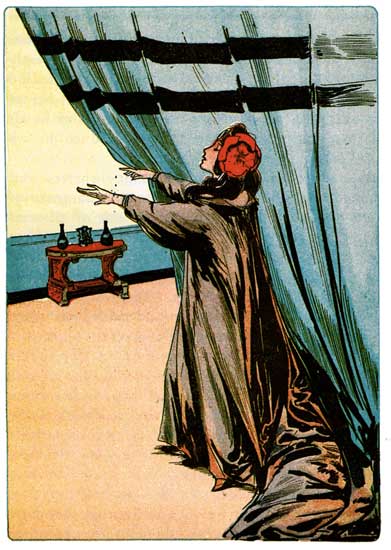

[Ozma] found herself in a splendid hall that was more beautiful and grand than anything she had ever beheld. The ceilings were composed of great arches that rose far above her head, and all the walls and floors were of polished marble exquisitely tinted in many colors. Thick velvet carpets were on the floor and heavy silken draperies covered the arches leading to the various rooms of the palace. The furniture was made of rare old woods richly carved and covered with delicate satins, and the entire palace was lighted by a mysterious rosy glow that seemed to come from no particular place but flooded each apartment with its soft and pleasing radiance.

Ozma passed from one room to another, greatly delighted by all she saw. The lovely palace had no other occupant, for the Nome King had left her at the entrance, which closed behind her, and in all the magnificent rooms there appeared to be no other person.

Upon the mantels, and on many shelves and brackets and tables, were clustered ornaments of every description, seemingly made out of all sorts of metals, glass, china, stones and marbles. There were vases, and figures of men and animals, and graven platters and bowls, and mosaics of precious gems, and many other things. Pictures, too, were on the walls, and the underground palace was quite a museum of rare and curious and costly objects.

For all his magnificence, the Nome King lacks taste. In their 1897 book The Decoration of Houses, which appeared ten years before Ozma of Oz, Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, Jr. discussed the need to limit one’s bric-a-brac for fear that it will cover up the elegant lines of a house. Questioning whether beauty can be achieved by “the indiscriminate amassing of “ornaments,’” the authors go on to conclude,

Decorators know how much the simplicity and dignity of a good room are diminished by crowding it with useless trifles. Their absence improves even bad rooms, or makes them at least less multitudinously bad. It is surprising to note how the removal of an accumulation of knick-knacks will free the architectural lines and restore the furniture to its rightful relation with the walls.

I am here to testify that removing bric-a-brac from a house does indeed restore architectural lines. Not that the architectural lines in our cookie cutter house are all that interesting. Nevertheless, I’m realizing the degree to which bric-a-brac, even bric-a-brac that has personal meaning, clutter up our spaces.

In Wharton’s and Codman’s eyes, accumulating bric-a-brac indicates vulgarity. Especially bad is when the bric-a-brac is expensive:

The one-dollar china pug is less harmful than an expensive onyx lamp-stand with moulded bronze mountings dipped in liquid gilding. It is one of the misfortunes of the present time that the most preposterously bad things often possess the powerful allurement of being expensive. One might think it an advantage that they are not within every one’s reach; but, as a matter of fact, it is their very unattainableness which, by making them more desirable, leads to the production of that worst curse of modern civilization—cheap copies of costly horrors.

Wharton wrote her book at the same time that Thorstein Veblen was writing The Theory of the Leisure Class, in which he coined the phrase “conspicuous consumption.” America was well on its way to becoming a modern consumer society, and people used bric-a-brac to persuade themselves they had achieved middle class status.

As I sort through our worldly possession, I am reminded how enmeshed I am in consumer society. How much more money would Julia and I have had for, say, travel or charity had we not spent it on all this stuff?

Recall that, in Ozma of Oz, Ev’s royal family becomes bric-a-brac because the king fails to value what is most important. Ultimately, he experiences remorse and leaps into the sea. Ozma, by contrast, prioritizes people over things. It’s a lesson we must keep teaching ourselves.