Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Tuesday

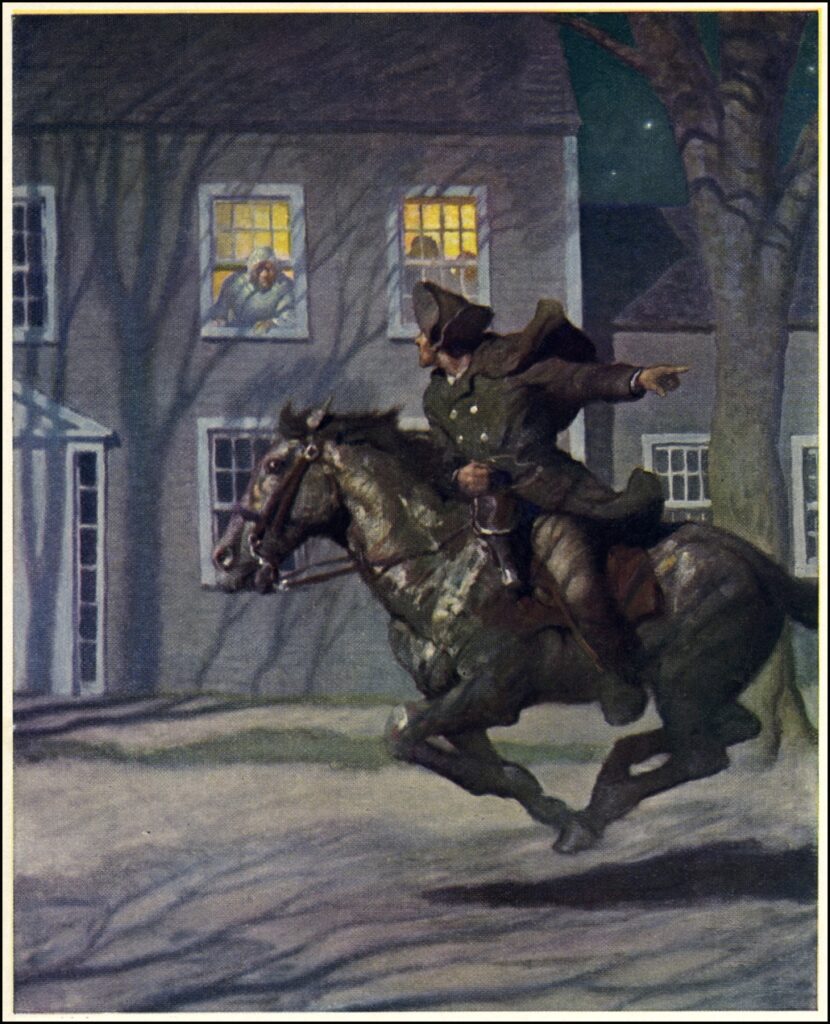

With Donald Trump fantasizing himself as a king, it’s time (as I noted yesterday) to revisit some of our classic poems about the American Revolution. Longellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride” has passages in it that, in light of recent developments, chill the blood.

Take, for instance, the spy work undertaken by Revere’s “friend” (probably Christ Church sexton Robert Newman). Instructed to figure out whether the British troops will come by land or by sea, he detects them heading for “their boats on the shore.” The “muster of men” he witnesses has me thinking of Trump’s plans for the military once he strips it of responsible leadership and of military lawyers who would throw up legal “roadblocks” (Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s term) to marching on American civilians:

Meanwhile, his friend, through alley and street

Wanders and watches with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers

Marching down to their boats on the shore.

We no longer need daring midnight rides to alert us to the threats that are coming. But we do need intrepid reporting, which we have not been getting from a mainstream media that failed to label Trump as the fascist threat he is proving to be. Our current versions of Newman, Revere, Samuel Dawes, and William Prescott (the latter two rode with Revere that night) are increasingly proving to be those independent outlets not in thrall to billionaire owners.

In the poem, Longfellow talks about how “the fate of a nation was riding that night” and how the sparks struck out by the galloping horse “kindled the land into flame with its heat.”

It appears that, thanks to such organizations as Meidas+ and various substack newsletters, the kindling is beginning. Angry voices, many in deeply red Congressional districts, have been besieging their members of Congress in town meetings. We are increasingly seeing large demonstrations, and lawyers have been attacking Trump and Elon Musk’s executive orders every chance they get. It remains to be seen how effective this all proves to be but Americans are beginning to rally.

The lesson that Longfellow draws from Revere’s ride is that the need for such a wake-up call is not confined to the past. “Throughout all our history,” he declares, we will require the night rider’s “cry of defiance, and not of fear.” “Eternal vigilance,” various activists have stated throughout our history, “is the price of liberty”:

A cry of defiance, and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

It so happens that Longfellow wrote “Paul Revere’s Ride” in 1860 to awaken America to the danger of civil war, the poem being composed less than a year before confederate soldiers fired upon Fort Sumpter. We are in our “hour of darkness and peril and need.” The poem, which I used to regard as one of those sing-songy affairs trafficking in patriotic platitudes, now speaks with a fierce urgency.

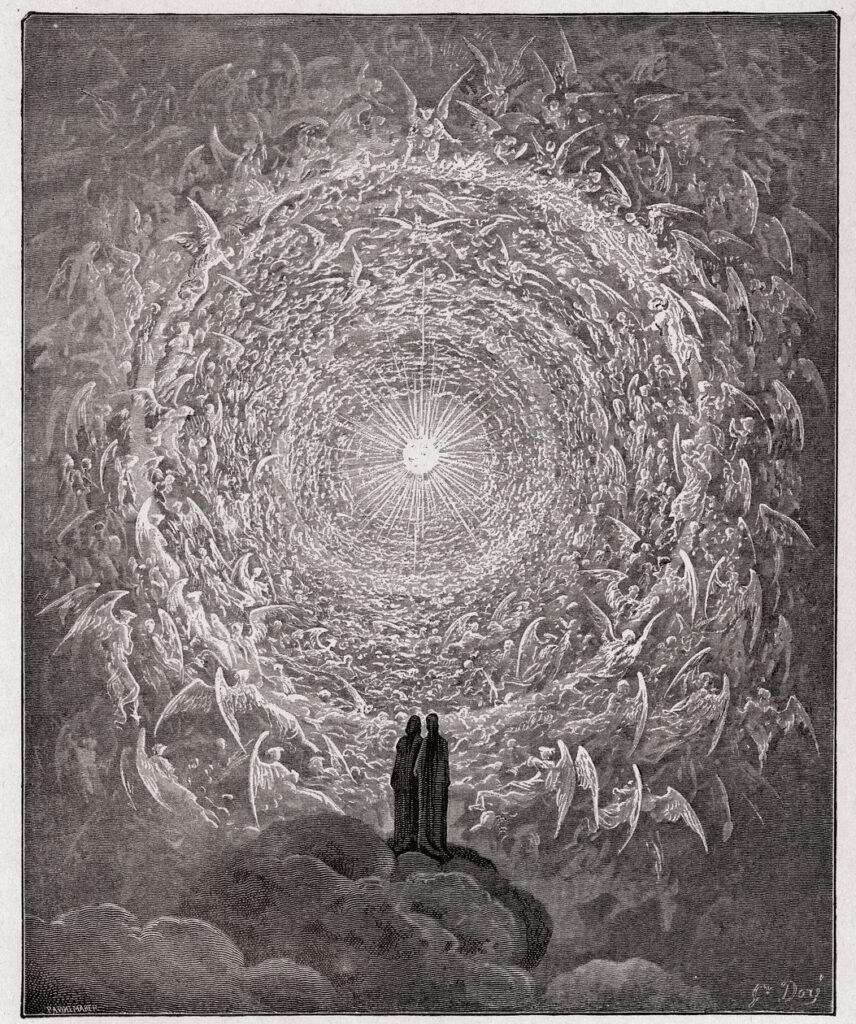

The great German cultural observer Walter Benjamin describes this transition to relevancy. In his “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” he writes about moments when the past becomes “charged with the time of the now” and is “blasted out of the continuum of history.” It is as though time falls away and we reach through history to “seize hold of a memory.” The American Revolution did this with the Roman republic (which is one reason why there’s a statue of George Washington wearing a toga), and we in turn may increasingly do the same with our own revolution. After all, the man in charge is tweeting out images of himself wearing a crown.

In other words, ask not for whom the rider rides. He rides for thee.