Friday

I received a comforting e-mail from an old friend in response to Monday’s post about my “intense busyness” in the face of my mother’s death. Steve Rhodes, artist and longtime resident of Iowa City, sent me a story told by 4th century BC Taoist philosopher Chuang Tzu (a.k.a. Zhuang Zhou).

I had worried that I was using busyness to mask my grieving, with the result that I neglected self care. Steve wrote that the balancing act between public performance and private reflection is a difficult one, especially for the oldest child. As he put it,

The busyness of grieving is the lot of the eldest child or of the surviving spouse, who usually find themselves charged with the ceremony and ritual of collective grief, and with the dispensations and the legal formalities.

As he himself has twice been in this situation, Steve could speak with authority. “I am not sure whether this busy mode of grieving arises from something inherent in my own psychology of coping with strong emotions,” he wrote,

or if it is more like what we refer to as eldest-child syndrome, where the external circumstances of family are served by chance upon us, controlling our responses in these collective moments of deepest feeling. Was I drawn to positions of busy administration by internal inclination or by external expectations?

Then he cited Chuang Tzu’s story, which as he said “has always sustained me at such times, providing lightness at a dark time.” This in spite of the fact that Steve says he still doesn’t fully understand it, even after 50 years. Here it is:

“Tsu Sang Hu, Ming Tsu Fan, and Tsu Chin Chang were acquaintances. They said to each other, “Who can be together without togetherness and cooperate without cooperation? Who can soar up to heaven, wander through the clouds, and pass beyond the limits of space, unmindful of existence, forever and ever?” Then the three looked at one another and laughed. Having no disagreement among themselves, they became fast friends.

“After some time, Tsu Sang Hu died. Before the burial, Confucius heard of his death and sent his disciple Tsu Kung to attend the mourning. Tsu Kung found that one of the friends was composing a song and the other was playing a lute. They sang together in unison, ‘Oh Sang Hu! Oh Sang Hu! You have gone back to your true self while we remain as men. Alas! Alas!’

“Tsu Kung hurried in and said, ‘May I ask something? Is that appropriate, singing in the presence of a corpse?’

“The two looked at each other and laughed. ‘What does he know about ceremony?’ they said.”(Inner Chapters, trans. Feng and English, 1974, p. 133)

I too find the story consoling. In my case, I see Tsu Kung so blinded by the formalities of ceremony that he misses the meaning. Sang Hu’s friends, by contrast, know that their union with him is so transcendent that injunctions not to sing in the presence of a corpse are meaningless. After all, if they could be “unmindful of existence” while all three were alive, then the death of one is irrelevant.

The story brings to mind someone’s observation at the community gathering, where we filled up an entire hall with people who cared for my mother. She so loved company, and loved my daughter-in-law’s singing and my sons’ humor, that I noted her absence seemed all wrong. “She should be here,” I said, to which this friend replied, “She was here all right.” And I knew then that she was.

Steve ended his note with an avowal that I also found immensely comforting. Commenting on our decades-long friendship, he wrote,

I’m thinking of you as I remember Phoebe. What unlikely happenings brought us to each other. Having no disagreement among ourselves, we became fast friends.

Yes.

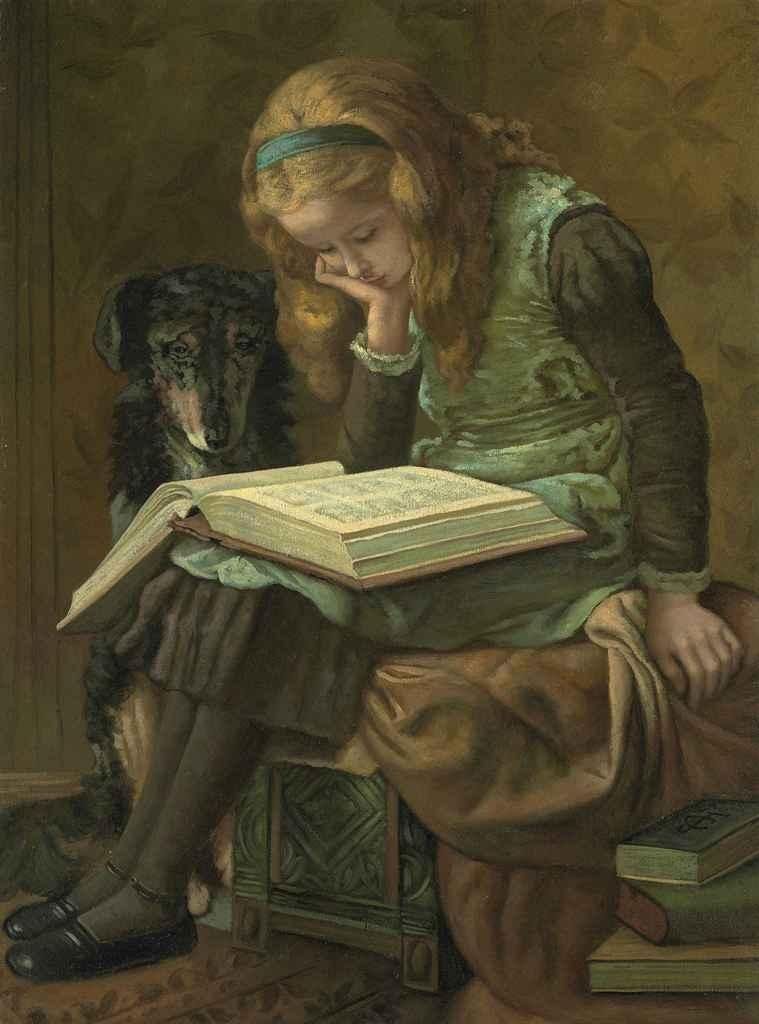

Further thought: Steve recently lost his wife Judy, who was Julia’s inspiring English teacher in her last year of high school. Judy recommended Carleton College, where she and Steve had met, and it was where Julia and I would meet three years later. Every time we visited Julia’s Iowa relatives, we would look up Judy and Steve and our children would play with their children.

Anyway, Steve said that Judy “often remarked how she learned the truth about death and grieving in Tristram Shandy.” I’ll explore this further in a future post but I suspect it has something to do with rejecting rigid formal responses (such as we are always getting from theory-obsessed Walter Shandy) and opting instead for lived experience—just as Sang Hu’s friends reject rigid ceremonial rules for a response that comes from deep within.