Spiritual Sunday

My good friend Sue Schmidt, who regularly contributes spiritual posts to this blog, alerted me to David Whyte’s poem “Finisterre” in anticipation of today’s Gospel reading about Jesus walking on the Sea of Galilee. For Whyte, the episode represents Jesus treading uncharted paths. You “abandon the shoes that had brought you here right at the water’s edge,” he writes,

not because you had given up

but because now, you would find a different way to tread,

and because, through it all, part of you would still walk on,

no matter how, over the waves.

Here’s the passage from Matthew (14:22-27):

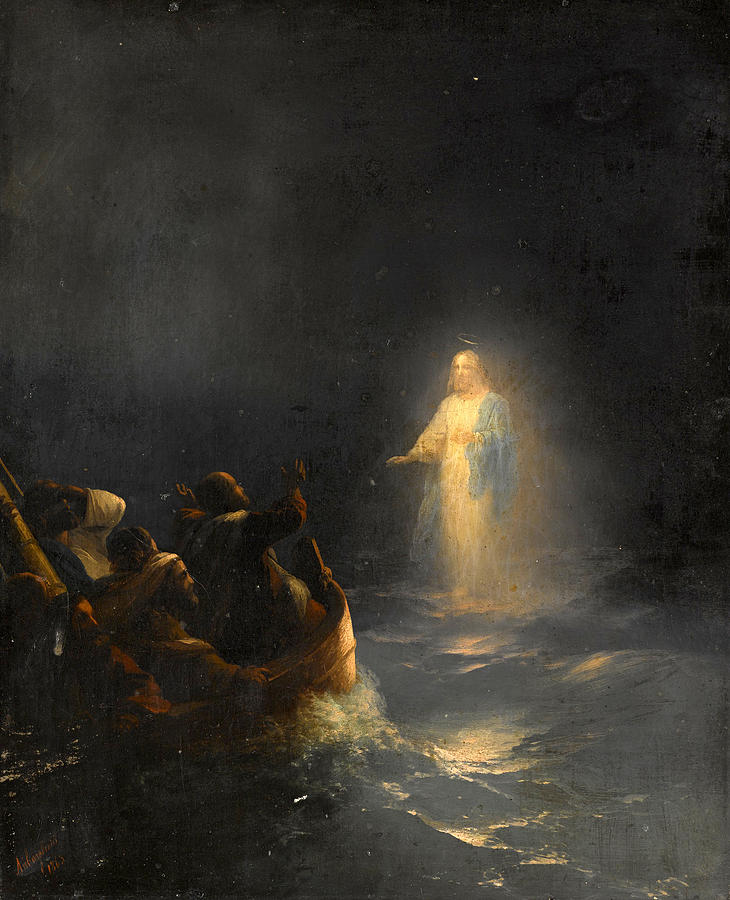

Jesus made the disciples get into the boat and go on ahead to the other side, while he dismissed the crowds. And after he had dismissed the crowds, he went up the mountain by himself to pray. When evening came, he was there alone, but by this time the boat, battered by the waves, was far from the land, for the wind was against them. And early in the morning he came walking toward them on the sea. But when the disciples saw him walking on the sea, they were terrified, saying, “It is a ghost!” And they cried out in fear. But immediately Jesus spoke to them and said, “Take heart, it is I; do not be afraid.”

The Jesus in Whyte’s poem is following his shadow, “going where shadows go.” Because what we call life won’t let Jesus accomplish his mission’’—”no way to your future now but the way your shadow could take”—he follows the sun into the dark, emptying his bags and crossing over where the ground turns to ocean. Or as Mary Oliver describes it “In Blackwater Woods,” he will be traversing

the black river of loss

whose other side

is salvation,

whose meaning

none of us will ever know.

As I interpret the frayed letters mentioned in the poem, they are the scriptures, which have gotten Jesus this far but which he can now release (or set fire to), letting them drift ahead of him “on the western light.” God’s plan, after all, has been realized in Jesus’s ministry—“Today the scripture has been fulfilled”–as Jesus takes the path “the sun had taken.”

According to Wikipedia, Finisterre is a peninsula on the west coast of Galicia, Spain that in Roman times “was believed to be the end of the known world.” It derives from finis terrae, meaning “end of the earth,” which makes it a perfect title for this poem.

The road in the end taking the path the sun had taken,

into the western sea, and the moon rising behind you

as you stood where ground turned to ocean: no way

to your future now but the way your shadow could take,

walking before you across water, going where shadows go,

no way to make sense of a world that wouldn’t let you pass

except to call an end to the way you had come,

to take out each frayed letter you had brought

and light their illumined corners; and to read

them as they drifted on the western light;

to empty your bags; to sort this and to leave that;

to promise what you needed to promise all along,

and to abandon the shoes that had brought you here

right at the water’s edge, not because you had given up

but because now, you would find a different way to tread,

and because, through it all, part of you would still walk on,

no matter how, over the waves.

In my conversation with Sue, I mentioned that Lucille Clifton also refers to the Biblical passage in her poem “questions and answers.” Frequently asked about her confidence–how she is able to stand so firmly—she herself isn’t sure. After all, like shallowly rooted cacti in a desert, she doesn’t have much to support her, being a black woman in America and a former victim of parental child abuse. She concludes that the process is like Jesus taking his first step upon the water:

what must it be like

to stand so firm, so sure?

in the desert even the saguro

hold on as long as they can

twisting their arms in

protest or celebration.

you are like me,

understanding the surprise

of jesus, his rough feet

planted on the water

the water lapping

his toes and holding them.

you are like me, like him

perhaps, certain only that

the surest failure

is the unattempted walk.

Clifton’s poem is less metaphysical than Whyte’s since the walk he refers to is into the realm of death, not just the realm of uncertainty. Nevertheless, the miraculous is involved in each of the two journeys. For both Jesus and Lucille, there is “no way to make sense of a world that wouldn’t let you pass/ except to call an end to the way you had come.”