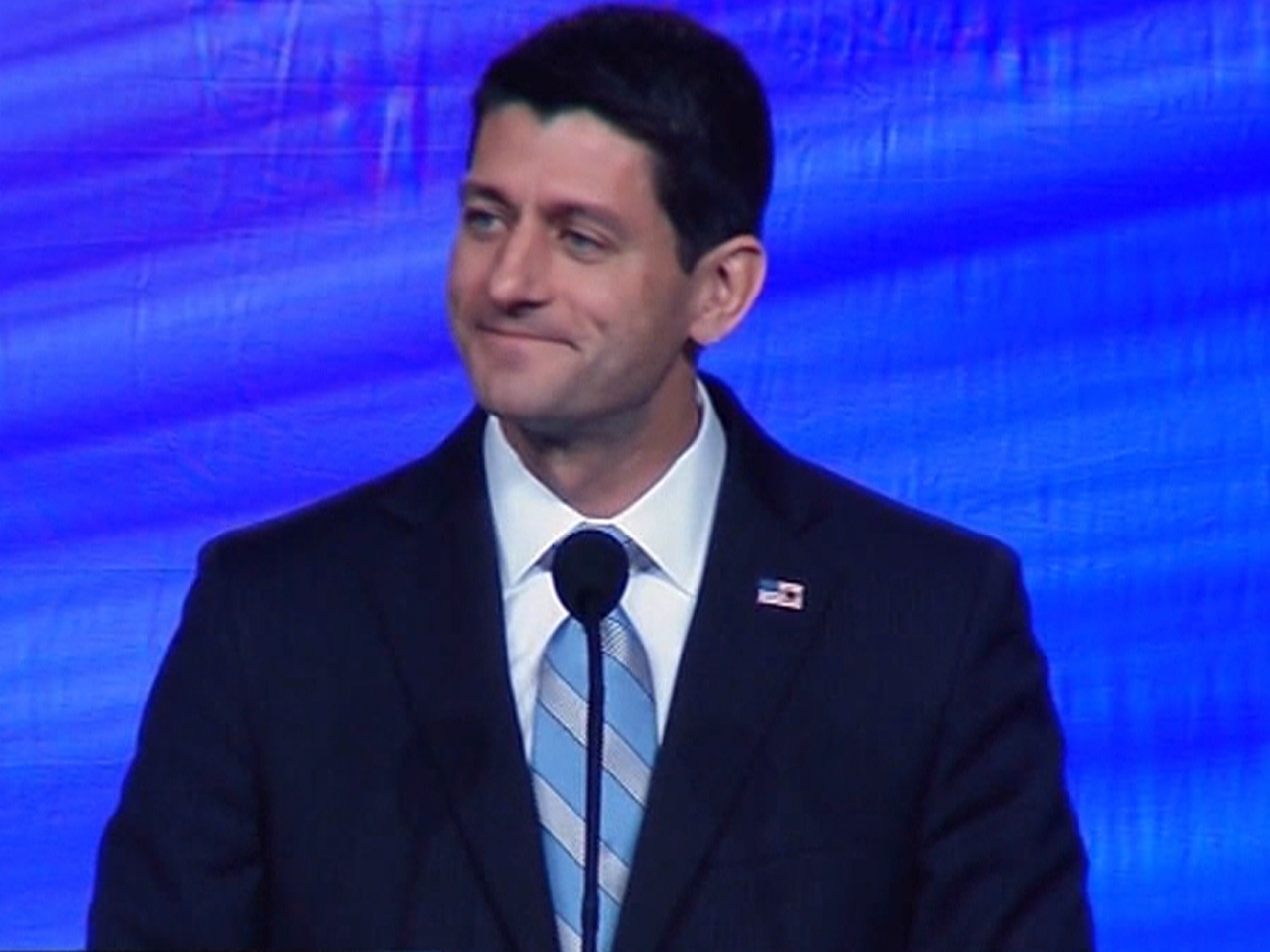

In his speech before the AARP the other day, Paul Ryan made me feel old for the first time in my life. I’m 61 but somehow think of myself as much younger (what a surprise!). There I was, however, having the same reaction to the videoclip of the 42-year-old Ryan promising to repeal Obamacare as those booing seniors in attendance.

I was surprised at my strong reaction since I knew in advance that I disagreed with the GOP vice presidential candidate. But it wasn’t what he said that most irritated me. It was his mannerism. He struck me as a smug and arrogant know-it-all (I’ll avoid the word “whippersnapper”) who thought he had all the answers but in fact had no clue about how life really works. In other words, I was reacting like an old person.

Also, like a number of commentators, I saw Ryan as a living reincarnation of Eddie Haskell from Leave It to Beaver. As Jonathan Bernstein explains,

If you young’ns don’t remember, Eddie Haskell was Wally Cleaver’s friend who was noted for “his unctuous politeness to adults and his weasly, sharp-tongued meanness to everybody else.” The great thing about Eddie Haskell as a character, though, was how utterly phony his act was, and therefore how ineffective it was; Ward and June were never, if I recall correctly, even remotely tempted to fall for it. Which, of course, is pretty much how I feel about Ryan.

Or as another blogger put it,

He has this whole persona of ‘Not me Mr. Cleaver! I didn’t cut your Medicare it was him!’

Anyway, I was wrestling with this new perspective on myself and thought of the passage in Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas where Prince Nekayah talks about the fraught relations between young and old. The work is about the elusive search for happiness, and the princess reports that she can’t find any prospects for happiness within families:

The opinions of children and parents, of the young and the old, are naturally opposite, by the contrary effects of hope and despondency, of expectation and experience, without crime or folly on either side. The colors of life in youth and age appear different, as the face of Nature in spring and winter. And how can children credit the assertions of parents which their own eyes show them to be false?

Few parents act in such a manner as much to enforce their maxims by the credit of their lives. The old man trusts wholly to slow contrivance and gradual progression; the youth expects to force his way by genius, vigor, and precipitance. The old man pays regard to riches, and the youth reverences virtue. The old man deifies prudence; the youth commits himself to magnanimity and chance. The young man, who intends no ill, believes that none is intended, and therefore acts with openness and candor; but his father; having suffered the injuries of fraud, is impelled to suspect and too often allured to practice it. Age looks with anger on the temerity of youth, and youth with contempt on the scrupulosity of age. Thus parents and children for the greatest part live on to love less and less; and if those whom Nature has thus closely united are the torments of each other, where shall we look for tenderness and consolations?

I consider Johnson one of the wisest men who ever lived, and he hits the nail on the head over and over in this discussion. Yes, we old people are more trusting of “slow contrivance and gradual progression” (that’s why we are less disappointed in Obama than some young people—we didn’t expect him to perform miracles) and are skeptical of those who trumpet “genius, vigor, and precipitance.” Yes, we are focused on riches (economic security) whereas Ryan is drawn more to virtue (purist ideology in his case). Yes, we elders value prudence and are worried about those who trust themselves to magnanimity and chance—which means that we are often not agents of significant change.

I am angry with Ryan’s “temerity,” which seems willing to upend whole systems (Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security) and replace them with dubious market-based solutions, and he in turn sees us elders (perhaps contemptuously) as overly cautious and scrupulous. Although I don’t think Ryan “acts with candor and openness” (sometimes just the opposite), he at least has had the openness to take on the politically toxic issue of exploding entitlement programs, and it is true that we suspicious elders, if not exactly guilty of fraud, are sometimes guilty of using Medicare in ways that are unsustainable.

This generational divide is going to become acute as we boomers flood into our country’s social programs for the elderly. Johnson is right to predict torments. After all, we elders have the limitations as well as the wisdom of “despondency” and “experience” and the next generation has the blindnesses as well as the energy of “hope” and “expectation.” Nekayah is correct in noting that, even if none of us intend any ill and even if there is “no crime or folly on either side,” the situation still has plenty of potential for conflict:

In families where there is or is not poverty there is commonly discord. If a kingdom be, as Imlac tells us, a great family, a family likewise is a little kingdom, torn with factions and exposed to revolutions. An unpracticed observer expects the love of parents and children to be constant and equal. But this kindness seldom continues beyond the years of infancy; in a short time the children become rivals to their parents. Benefits are allowed by reproaches, and gratitude debased by envy.

At the very least in our American family, we can be aware of the dynamics that Johnson warns us about and humbly seek to avoid the pitfalls. It all begins with listening–really listening–to each other.