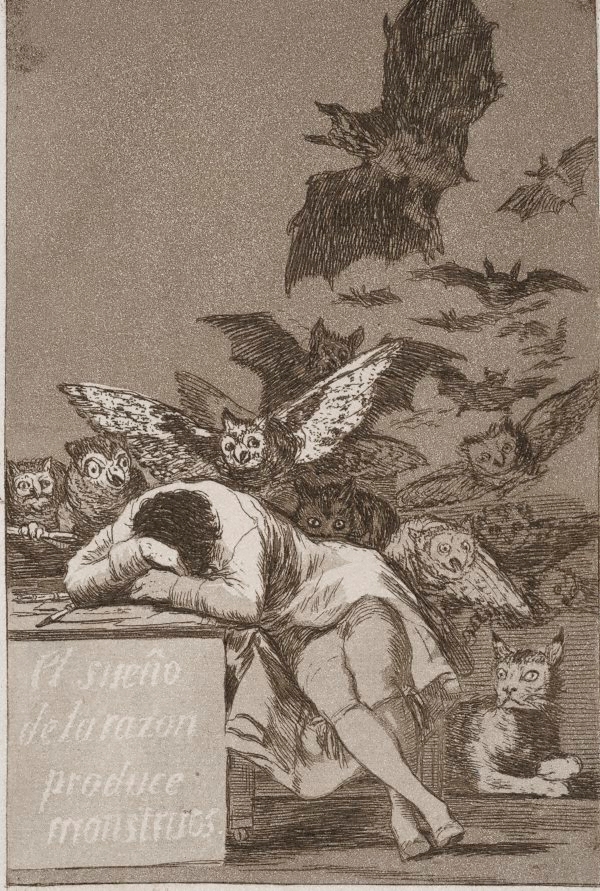

Goya, “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” (“Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters–united with her (reason), she (fantasy) is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels”)

Friday

The other day Eva Bahovec, a good friend who teaches in Ljubljana’s philosophy department, had me meet with two students preparing to write Women’s Studies dissertations. Although philosophy and Women’s Studies are not my areas of expertise, Bogdan Repič and Polonca Mesec want their studies to have a literary component, which is where I came in. In today’s post, I expand on something I told them: literature is always smarter than we are and, when we immerse ourselves in a work, we take on its wisdom.

This is not to say that literature is superior to philosophy (although I myself would rather read literature). Each discipline has its own special way of knowing and, in any case, this isn’t a competition. Literature’s way of knowing, however, adds emotional and spiritual intelligence to rational intelligence. Along with grasping literature intellectually, we also feel it and, in addition, we sense broader import. This happens all at once.

I told Bogdan and Polonca that I can speak confidently from having spent a lifetime systematically applying literature to life. When I find a successful match between a literary work and something in the world, it’s as though I can “see into the life of things” (Wordsworth). In following the fictional, poetic, or dramatic argument, I chance upon insights I would not have had otherwise.

Like Homer, our abilities are enhanced when we invoke the literary muse. We can think of literature as the river into which the infant Achilles is dipped, immersion bestowing warrior attributes. To adapt a formulation found in Yeats’s “Leda and the Swan,” we put on literature’s knowledge when we are in the grip of its power.

Only unlike with Achilles, the power doesn’t last, invariably wearing off so that we return to the same plane of reality as everyone else. To regain it, we must immerse ourselves again in a poem or play or work of fiction. Fortunately, the waters never lose their potency.

But back to applying literature to philosophy. What literature gains from holistic knowing, it loses in directness. “The poet, he nothing affirmeth,” Sidney said, alluding to the way that literature pulls us into its own world. In that respect, literature is like the Delphic oracle, whose words must be interpreted if they are to prove useful.

Philosophy, psychology, and sociology all have their own discourse, complete with conventions concerning argumentation, evidence, and testing and with a long history of conversations that practitioners must become familiar with. (Philosophy’s conversations go back 2500 years.) When a work of literature enters the world of the social sciences or humanities, it no longer looks like it did before. The various disciplines mine it for what they can use, and what the philosophers take away will be different than what the psychologists or political scientists take away. And that’s okay.

I therefore suggested to Bogdan and Polonca that they find a literary work or author that addresses their issues. The selection process should be intuitive as well as a rational. If the work is inspiring, if one is moved by its beauty as well as by its insight, then the subsequent exploration will not dwindle to a dry academic exercise. I think of such exploration as a spooling out from a potent emotional, spiritual, and intellectual core.

This image of power radiating outward brings to mind an analogy found in Plato’s Ion. Seeking to understand the power accessed by Ion, the age’s foremost performer of Homer, Socrates offers the following image:

The gift which you possess of speaking excellently about Homer is not an art, but, as I was just saying, an inspiration; there is a divinity moving you, like that contained in the stone which Euripides calls a magnet, but which is commonly known as the stone of Heraclea. This stone not only attracts iron rings, but also imparts to them a similar power of attracting other rings; and sometimes you may see a number of pieces of iron and rings suspended from one another so as to form quite a long chain: and all of them derive their power of suspension from the original stone. In like manner the Muse first of all inspires men herself; and from these inspired persons a chain of other persons is suspended, who take the inspiration. For all good poets, epic as well as lyric, compose their beautiful poems not by art, but because they are inspired and possessed.

I should add that Plato, rational to a fault, does not see this as altogether a good thing. Comparing inspired artists to maddened Dionysian revelers, he says that lyric poets “are not in their right mind when they are composing their beautiful strains.” This is why he banishes poets from his perfect republic. Only the purely rational need apply.

Women’s Studies, however, has every reason to be suspicious of Platonic reason, and in fact some feminist philosophers have decried the absence of an affective or emotional dimension in classic philosophy. As they search for ways to expand philosophy’s reach, these Slovenian students will find an invaluable ally in literature.