Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Tuesday

I never cease to marvel at how small scenes from a novel read in childhood—scenes that others might overlook—are woven into our understanding of the world. When the scene intersects with something we encounter in real life, we have a powerful framework for processing this new information.

Today I’m thinking of my first encounter with real hunger. Having been raised in a middle-class household, I have never experienced deprivation. But Sewanee is located in the Southern Appalachians, where Hunger exists—or at least it did so in my childhood. Two incidents come to mind.

Before recounting them, however, I share a passage from Carlo Collodi’s Adventures of Pinocchio (1883), which primed me for what I was to witness. The novel, I hasten to mention, is nothing like the Disney movie. For one thing, early in the book Pinocchio throws a hammer at the talking cricket that functions as his conscience, killing it (“With a last weak “cri-cri-cri” the poor Cricket fell from the wall, dead!”). After that, the mischievous marionette can receive guidance only from the cricket’s ghost. Pinocchio is unexpectedly grim for a children’s book—at one point Pinocchio barely survives after the Fox and the Cat hang him by the neck from a tree—and part of the grimness involves starvation.

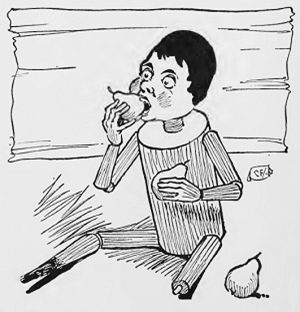

In the scene I remember, Pinocchio has been frantic with hunger until Geppetto returns home with three pears, at which point he gets picky. What transpires is a lesson in not wasting food:

“If you want me to eat them, please peel them for me.”

“Peel them?” asked Geppetto, very much surprised. “I should never have thought, dear boy of mine, that you were so dainty and fussy about your food. Bad, very bad! In this world, even as children, we must accustom ourselves to eat of everything, for we never know what life may hold in store for us!”

“You may be right,” answered Pinocchio, “but I will not eat the pears if they are not peeled. I don’t like them.”

And good old Geppetto took out a knife, peeled the three pears, and put the skins in a row on the table.

Pinocchio ate one pear in a twinkling and started to throw the core away, but Geppetto held his arm.

“Oh, no, don’t throw it away! Everything in this world may be of some use!”

“But the core I will not eat!” cried Pinocchio in an angry tone.

“Who knows?” repeated Geppetto calmly.

And later the three cores were placed on the table next to the skins.

Pinocchio had eaten the three pears, or rather devoured them. Then he yawned deeply, and wailed:

“I’m still hungry.”

“But I have no more to give you.”

“Really, nothing—nothing?”

“I have only these three cores and these skins.”

“Very well, then,” said Pinocchio, “if there is nothing else I’ll eat them.”

At first he made a wry face, but, one after another, the skins and the cores disappeared.

“Ah! Now I feel fine!” he said after eating the last one.

And then this very didactic book delivers its message:

“You see,” observed Geppetto, “that I was right when I told you that one must not be too fussy and too dainty about food. My dear, we never know what life may have in store for us!”

Now for my childhood stories. Appalachian poverty runs deep, and in some of the communities around Sewanee were people living in tarpaper shacks. There were no free-lunch or free-breakfast programs in those days, and I remember a couple of boys in seventh grade leaving morning classes early in order to sweep out the dining hall in exchange for lunch money.

At one point in fifth grade we had an Easter egg hunt, with the prize being a large popcorn rabbit held together by some sweet, sticky substance, maybe caramel.

I took the hunt very seriously and am pretty sure I found the most eggs. But classmate Curtis (not his real name) claimed that he had found the most and, without counting what was in our bags, the teacher presented him with the rabbit. I remember feeling cheated and aggrieved.

Or I felt that way until I saw what happened next. Curtis grabbed the rabbit and bit into it with ferocity such as I had never seen before, devouring it to the last kernel. There was no dainty nibbling around the edges. I knew—in part from having reading Pinocchio and in part by the intensity of the moment—that I was in the presence of Hunger. At that moment, I was glad that, whether fairly or not, Curtis had won that rabbit. My own desires and needs were secondary.

This experience was reenforced a couple of years later in seventh grade. We had some kind of bread or rice pudding for lunch one day, into which the chef had much so much sugar or something that it was too rich too eat. Kids will eat almost anything sweet, but in this case no one could get it down. We all left it on our plates.

Well, almost all of us. I remember seeing Curtis, back behind the lunch counter, shoveling down the food from the large bowl out of which it had been served. He was using one of the large serving spoons and appeared to be (as the expression went) “in hog heaven.” Once again, I recognized I was in the presence of Hunger.

I’m not sure I would have connected the dots had I not read Pinocchio. The story had lodged in my head because of my strong initial response—I had been torn between feeling sorry for the marionette and ashamed at his antics—and now a life incident was prompting me to recall it.

All of which is to say that, whether at home or at school, children must be introduced to a constant stream of books. Adults cannot always predict what they will take away with them.