Tuesday

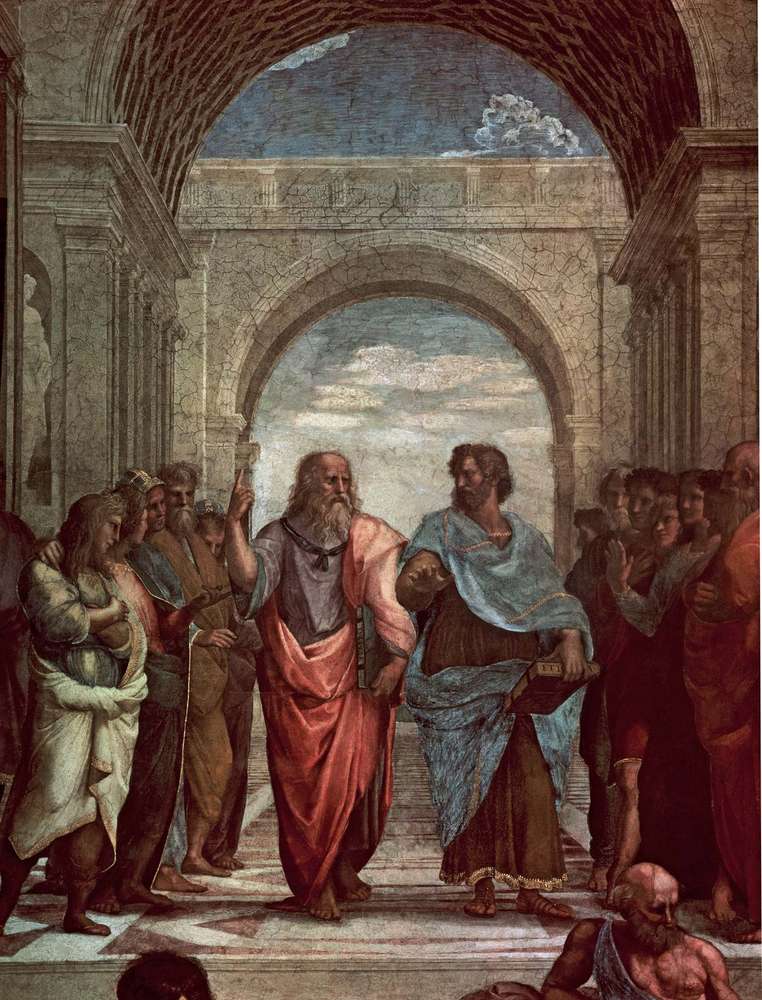

The more I work with Plato’s and Aristotle’s views of literature (for my book Does Literature Make Us Better People?), the more I realize that Aristotle is directly responding to his old teacher, even though he doesn’t come out and say so directly. Although, as I noted last week, Aristotle is never as specific about literature’s impact upon audiences as Plato is, I think I finally understand how his Poetics works as a counterargument.

Think about it this way:

Plato: Worse living through Homer and Hesiod

Aristotle: Better living through Aeschylus, Socrates, and Euripides (oh, and also Homer)

Interestingly, both men love literature. Plato, however, is suspicious of his love whereas Aristotle embraces it. Because Plato sees philosophy and poetry at odds, at one point comparing poetry to wild Bacchanalian dancing, he reluctantly banishes poets from his ideal society. The banishment extends to his “beloved” Homer.

One can see how Plato responds to Homer by how he fears others will respond. Take for instance his worries about the scene where Odysseus encounters Achilles in the underworld:

“But was there ever a man more blest by fortune

than you, Akhilleus? Can there ever be?

We ranked you with immortals in your lifetime,

we Argives did, and here your power is royal

among the dead men’s shades. Think, then, Akhilleus:

you need not be so pained by death.”

To this

he answered swiftly:

“Let me hear no smooth talk

of death from you, Odysseus, light of councils.

Better, I say, to break sod as a farm hand

for some poor country man, on iron rations,

than lord it over all the exhausted dead.

(trans. Robert Fitzgerald)

Plato is concerned that this scene will cause young warriors to turn cowardly on the battlefield. But could it be that the scene unnerves Plato because it affects him so deeply? Perhaps Homer so grips his mind that he believes he himself would falter should his courage be tested. Better to prevent young minds from encountering such scenes in the first place.

In contrast, Aristotle embraces the intense emotions that literature unleashes in audiences. He see as a plus the fact that audiences experience an emotional purging or purification—a catharsis—when they witness a great play. The more intense the catharsis, the greater the work.

Catharis, Aristotle tells us, is brought about by a combination of pity and fear: we pity what the tragic hero is enduring and we fear that the same could happen to us. If classicist Edith Hall is right that 5th century Greek tragedy captured the conflict between individuals seeking control over their own lives and circumstances that inexorably crush them (see last Thursday’s post), then spectators felt themselves understood and therefore less alone. They were crying for themselves. (“It is Margaret you weep for,” Gerard Manley Hopkins would say.)

While such weeping strikes Plato as unmanly, for Aristotle it is a sign that tragedy is capturing our essential human condition. This is why poetry for him is “a more philosophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular.” Great poetry, with its acute understanding of humans, knows “how a person of a certain type will on occasion speak or act, according to the law of probability or necessity; and it is this universality at which poetry aims in the names she attaches to the personages.”

History, by contrast, is limited by the particular examples: “for example—what Alcibiades did or suffered.”

Plato refuses to grant poetry this special insight into reality. For him, poetry is not only inferior to philosophy but to the practical crafts as well. For instance, if (as his theory of forms goes), there exists an ideal form of a chair that all chairs echo or descend from, then the poet sees neither that ideal form (only God can see it, and possibly philosophers), nor the imitation of the ideal (manufactured by the chair maker). Rather, the artist creates only an imitation of an imitation, and the artist’s audience is yet another step removed. Two degrees of separation from truth, in other words.

Or as Plato also puts it, you don’t read Homer to learn how to drive a chariot—or for that matter, how to become a statesman.

With his own focus on imitation, Aristotle contradicts his master. He’s not concerned with chairs or chariot driving but with the human condition. His contention that literature has a special grasp of universal truth has been echoed by many literary theorists since, among them Sir Philip Sidney, Samuel Johnson, Percy Shelley, Marx and Engels, and W.E.B. Du Bois. All argue that literature’s ability to express truth is its greatest strength, not to mention its primary responsibility. Forget your personal prejudices, they tell artists, and just give us reality. Or as Sidney puts it, “the poet, he nothing affirms.”

(As an aside, I note that philosophers have an on-going debate about whether Aristotle thinks poetry is higher than, not only history, but philosophy as well. Some argue that he thinks poetry’s insights can be folded into a philosophical framework (in which case it isn’t), others that poetry provides a radically different way of knowing. I myself am in the second camp, viewing literature at least on a par with philosophy if not higher. As I see it, literary knowing combines virtual experience with reflection whereas philosophy specializes only in intellectual reflection.)

Poetry, Aristotle says, springs from our desire to imitate, which in turns makes poetry a powerful teaching force: we desire instances of imitation to help us grow. Here’s how Aristotle puts it:

Poetry in general seems to have sprung from two causes, each of them lying deep in our nature. First, the instinct of imitation is implanted in man from childhood, one difference between him and other animals being that he is the most imitative of living creatures, and through imitation learns his earliest lessons; and no less universal is the pleasure felt in things imitated.

Different form of literature imitate different things. Epic and tragedy (Aristotle mentions Homer and Sophocles) imitate “higher types of character,” comedy (Aristophanes) lower types. As Aristotle puts it, “The graver spirits imitated noble actions, and the actions of good men. The more trivial sort imitated the actions of meaner persons.”

Speaking of action, Aristotle’s considers it more important than character in a tragedy. Through action, we see a person’s character put to the test. This character, Aristotle says, must be good and motivated by a moral purpose but must be brought down by some internal “error or frailty.” Because tragedies ennoble their protagonists, they also inspire imitation-hungry spectators. We grieve when they fall but also take away important lessons.

In the end, Aristotle has more faith than Plato in general audiences to make good choices when moved by literature. We see the same divide today between liberals and conservatives. Both philosophers, however, regard literature as a potent force.