Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

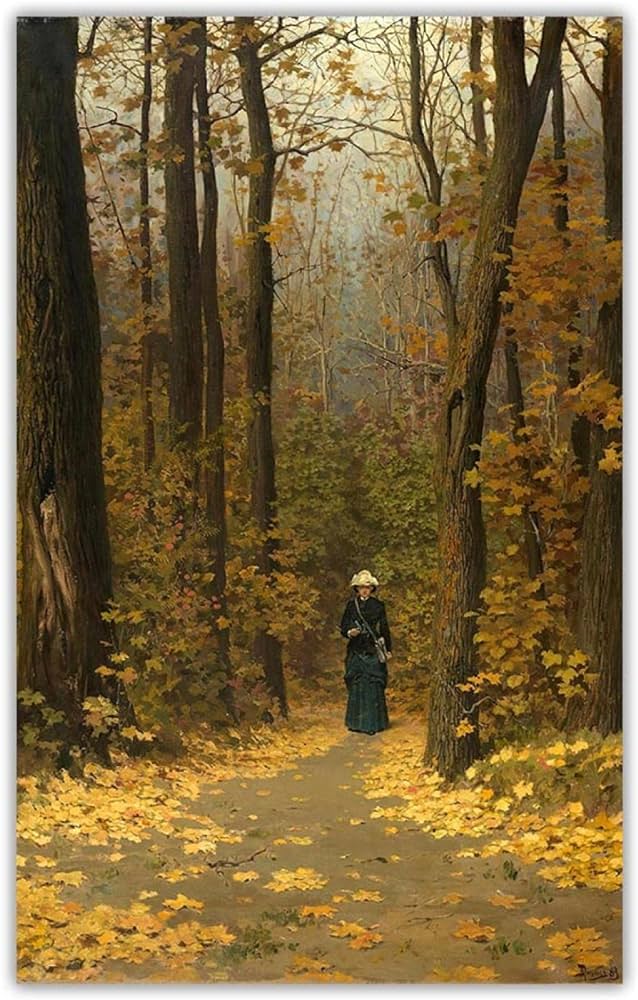

If you enjoy autumn strolls, check out the poetry of the 17th century Anglican cleric Thomas Traherne. My Faculty Reading Group, which has been discussing the work of such metaphysical poets as John Donne, George Herbert, and Henry Vaughan, has introduced me to Traherne, who is perpetually enthusiastic about the gifts he sees in the world around him. Walking, as he sees it, is one of the best ways of experiencing them.

Traherne makes a distinction between seeing with the eyes and seeing with the mind. The first is merely mechanical and does not involve noticing things. When we walk in this manner, Traherne says, we are like “dead puppets” who “may move in the bright and glorious day, yet not behold the sky.”

In his extended essay on walking, Henry David Thoreau makes a similar distinction. For him, it is the difference between the body and the spirit:

I am alarmed when it happens that I have walked a mile into the woods bodily, without getting there in spirit. In my afternoon walk I would fain forget all my morning occupations and my obligations to Society. But it sometimes happens that I cannot easily shake off the village. The thought of some work will run in my head and I am not where my body is — I am out of my senses. In my walks I would fain return to my senses. What business have I in the woods, if I am thinking of something out of the woods?

Actually, Thoreau prefers the word “sauntering,” which accentuates the randomness of the experience.

Traherne agrees. When we walk, he says, we should think of ourselves as bees gathering pollen. Or as he sensuously puts it,

To fly abroad like active bees,

Among the hedges and the trees,

To cull the dew that lies

On ev’ry blade,

From ev’ry blossom; till we lade

Our minds, as they their thighs.

For a moment, Traherne sounds Wordsworthian, suggesting that we lose something as we grow older:

A little child these well perceives,

Who, tumbling in green grass and leaves,

May rich as kings be thought…

Wordsworth similarly observes (in Intimations of Immortality), “But yet I know, where’er I go,/That there hath past away a glory from the earth.”

Unlike Wordsworth, however, Traherne, then assures us that these pleasures are equally available to adults:

But there’s a sight

Which perfect manhood may delight,

To which we shall be brought.

Apparently this is a theme for Traherne. In fact, as we were informed by Sewanee’s Renaissance specialist James MacDonald, Traherne has one note, which he plays over and over. One sees his non-stop enthusiasm in “Wonder” as well as in “Walking.” Here are two stanzas:

The skies in their magnificence,

The lively, lovely air;

Oh how divine, how soft, how sweet, how fair!

The stars did entertain my sense,

And all the works of God, so bright and pure,

So rich and great did seem,

As if they ever must endure

In my esteem.

A native health and innocence

Within my bones did grow,

And while my God did all his glories show,

I felt a vigour in my sense

That was all spirit. I within did flow

With seas of life, like wine;

I nothing in the world did know

But ’twas divine.

As one of our members put it, it’s like Blake’s Songs of Innocence without the accompanying Songs of Experience.

In this regard, Traherne differs from George Herbert, whom we had just discussed and who constantly grapples with mood swings and agonizing doubt. Although he, like Traherne often ends up with a deep appreciation of God’s bounty, he has to work harder to get there.

But if you want your walk to be unalloyed joy, Traherne is the poet for you.

Walking

By Thomas Traherne

To walk abroad is, not with eyes,

But thoughts, the fields to see and prize;

Else may the silent feet,

Like logs of wood,

Move up and down, and see no good

Nor joy nor glory meet.

Ev’n carts and wheels their place do change,

But cannot see, though very strange

The glory that is by;

Dead puppets may

Move in the bright and glorious day,

Yet not behold the sky.

And are not men than they more blind,

Who having eyes yet never find

The bliss in which they move;

Like statues dead

They up and down are carried

Yet never see nor love.

To walk is by a thought to go;

To move in spirit to and fro;

To mind the good we see;

To taste the sweet;

Observing all the things we meet

How choice and rich they be.

To note the beauty of the day,

And golden fields of corn survey;

Admire each pretty flow’r

With its sweet smell;

To praise their Maker, and to tell

The marks of his great pow’r.

To fly abroad like active bees,

Among the hedges and the trees,

To cull the dew that lies

On ev’ry blade,

From ev’ry blossom; till we lade

Our minds, as they their thighs.

Observe those rich and glorious things,

The rivers, meadows, woods, and springs,

The fructifying sun;

To note from far

The rising of each twinkling star

For us his race to run.

A little child these well perceives,

Who, tumbling in green grass and leaves,

May rich as kings be thought,

But there’s a sight

Which perfect manhood may delight,

To which we shall be brought.

While in those pleasant paths we talk,

’Tis that tow’rds which at last we walk;

For we may by degrees

Wisely proceed

Pleasures of love and praise to heed,

From viewing herbs and trees.