Tuesday

As I am in the throes of revising my book Does Literature Make Us Better People?, I’m sharing one of the chapters today rather than spending the time to write a blog post. The book has a series of short chapters on how thinkers over the ages have addressed the question. Enjoy.

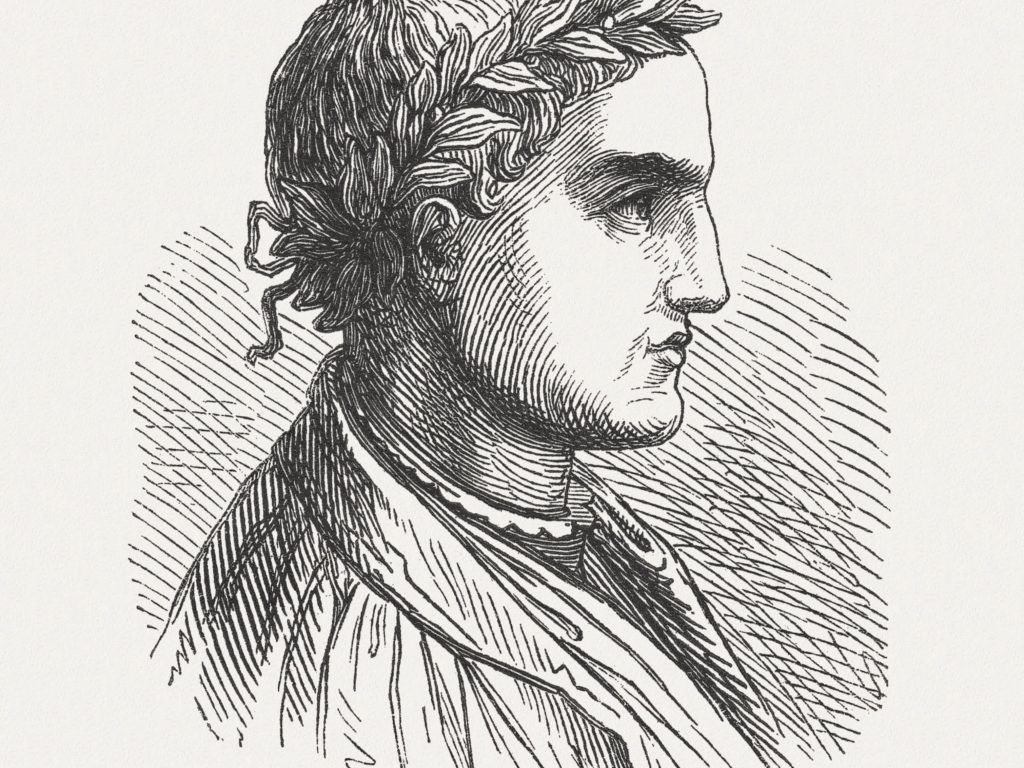

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65-8 BCE), author of the most important theoretical work about poetry to emerge from the Roman empire, lived an eventful early life. The son of a freedman, he fought with Brutus and Cassius against Mark Antony and Augustus as a young man, saw his family farm confiscated, and then later reconciled with Augustus after the latter became Caesar. Eventually Horace was rewarded for his odes and satires, many of which would become poetic models for centuries afterwards. Harry Eyres, who in Horace and Me: Life Lessons from an Ancient Poet explains how the poet is an indispensable guide for the Slow Movement, says that Horace remarkably managed to “carve out a space for lyric poetry in a pragmatic, increasingly instrumental and money-driven society.”

To the question of whether literature makes us better people, it is clearly the intent of Horace’s poetry to do so. Many of his poems are concerned with how to live a good life—he’s the author of “carpé diem” or “seize the moment”—and he often counsels taking “a middle way.” The value of his Ars Poetica (The Art of Poetry) for our purposes is that he directly addresses how poetry contributes to this endeavor. This 476-line poem, which for 1500 was regarded as an indispensable guide for practicing poets, recommends maintaining a balance between poetic delight and poetic utility.

The tension between delight and usefulness never goes away, with some people worrying that literature is spoiled when it is yoked to a serious agenda and others worrying that literature is frivolous when it is not. We’ve noted that, for Plato, the divide is so great that poets must be banished altogether from his republic, but Horace contends that we don’t have to choose. While he acknowledges that there are some poets who “wish either to profit or to delight,” the best poets “deliver at once both the pleasures and the necessaries of life.”

Horace sets up as, as opposites in the profit-delight tension, “the tribes of the senior” on the one hand and “the exalted knights” on the other. The first—call them grumpy old men—frown on anything that is not edifying whereas the latter—high spirited young men—“disregard poems which are austere”—by which he probably means preachy and moralistic. Earlier in the poem he talks about what happens with such young men as soon as they shake free of their guardians:

The beardless youth, his guardian being at length discharged, joys in horses, and dogs, and the verdure of the sunny Campus Martius; pliable as wax to the bent of vice, rough to advisers, a slow provider of useful things, prodigal of his money, high-spirited, and amorous, and hasty in deserting the objects of his passion.

If you want to get through to such minds, Horace says, set aside long-winded advice and “superfluous instructions.” This is not to say, however, that the poet should abandon education altogether. Entertain your audience but in a way that sticks close to truth. The poet “who joins the instructive with the agreeable,” Horace declares, “carries off every vote.”

Later theorists will second Horace’s advice. In his Defense of Poesie (c. 1580), poet Sir Philip Sidney says that those who “despise the austere admonitions of the philosopher, and feel not the inward reason they stand upon” may nevertheless “be content to be delighted” by poetry. Therefore, the poet can use beauty to lure them into goodness, “ere themselves be aware, as if they took a medicine of cherries.” In his Battle of the Books (1704), meanwhile, satirist Jonathan Swift characterizes Horace’s dual property of literature as “sweetness and light” and conveys the idea through the symbol of the bee, who makes both honey and wax (used for candles).

Even after asserting that delightful poetry can be used for practical ends, however, Horace still imagines (probably correctly) that, despite his arguments, skeptics still exist who will be “ashamed of the lyric muse, and Apollo the god of song.” He therefore leaves his delicate balancing act and brings out his big guns, piling up one poetic accomplishment upon another.

The legendary poet Orpheus, he says, “deterred the savage race of men from slaughters and inhuman diet”—Orpheus supposedly taught cannibals how to subsist on fruit—and tamed tigers and “furious lions.” Amphion, another figure from Greek mythology, built the walls of Thebes with his music (“was said to give the stones motion with the sound of his lyre”).

Other poets taught people civic responsibility; created a sense of the sacred; regulated sexual behavior (“prohibit[ed] a promiscuous commerce between the sexes”); taught civilization how to conduct marriages; designed cities; and established laws. Homer and the Spartan poet Tyrtaeus, meanwhile, “animated the manly mind to martial achievements with their verses.” Nor should we forget that oracles deliver their pronouncements in poetry and that poetry can be used as a guide to life and a way to praise princes. Oh, and one final thing: think of the delight we take in attending a play at the end of a long day of tedious work. Case closed.

Whether Horace actually believes that the strains of a lyre can shift stones, his encomium to poetry points to the power he senses in it. He knows that he himself is moved and then marshals a host of examples to prove that poetry works on others as well. He will not be the last to trumpet poetry’s practical accomplishments in response to accusations of frivolity—we’re about to see Philip Sidney take up his cause and run with it—but he was the first theorist to expressly argue that literature could be simultaneously serious and delightful, at once a practical tool and a joy unto itself.