Three years ago in my Early British Literature survey, Victoria Gottleib wrote about her bulimia in relationship to Milton’s Satan. (Victoria is now allowing me to use her name.) Last week I was gratified to witness Victoria’s remarkable senior project presentation where she discussed female self portraiture. It was inspiring to see how Victoria has built upon her early insights.

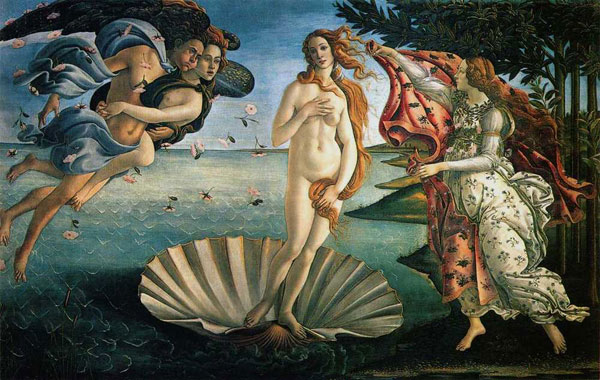

An Art and English double major, Victoria described a workshop she set up where women created self portraits in response to Kelly Cherry’s poem “Rising Venus” The poem is itself a response to Botticelli’s famous painting “The Birth of Venus.”

First, a couple of notes on Victoria essay’s about Paradise Lost. Victoria saw herself in Satan’s perfectionism and understood his self-destructive need for control:

Perhaps the Satanic sentiment I most personally relate to is Satan’s stubborn resolve that “To reign is worth ambition though in Hell:/Better to reign in Hell, than to serve in Heav’n.” Satan would rather have a warped attainment of “perfection” than relinquish his absolute control and accept his true nature, shortcomings and all, something with which I identify. As selfish and depraved as my eating disorder, my own personal hell, is, in my mind I “reign” over it and find solace in the control with which it provides me, despite its innate detriment.

As I wrote in that 2012 post, I had a conversation with Victoria after receiving her essay in which I mentioned that Milton could do even more than give her a description of her condition. He also points a way to healing. As I quote my reply, I should perhaps note that Milton’s God does not have to be interpteted religiously but can also be seen as selfless love:

I told her that the next logical step for the essay may also be the next step for herself: to look at the love that Milton’s God promises. God’s love is infinite, and true heroism is acknowledging, as Satan never does, that one is worthy to be loved in spite of the imperfections that one perceives in oneself. Milton’s Adam and Eve come to understand this, which is why they, not Satan, are the real heroes of Paradise Lost. They are the ones who have the humility to turn back to God.

Imagine how exciting I found it, therefore, to see Victoria, three years later, using poetry to help women with low self-esteem come to terms with their bodies.

In her project, Victoria wrote about destructive depictions of women in the media and how first wave and second wave feminist poets fought back through their own portraits. The poems Victoria examined were Adrienne Rich’s “Rape” and “Planetarium”; Lucille Clifton’s “Sisters” and “Wishes for Sons”; Sylvia Plath’s “Barren Woman”; Andrea Gibson’s “I Sing The Body Electric, Especially When My Power’s Out”; and Cherry’s “Rising Venus.” She also looked at the self portraits of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo.

In addition to “Rising Venus,” Victoria set up workshops reflecting upon “Planetarium” and “I Sing the Body Electric.” Here’s Cherry’s poem:

Rising Venus

By Kelly Cherry

They have it wrong:

I am not young,

was born old enough

to ride the rough

waves of the sea

without drowning, and immodestly.

Semen and seaweed clung

to my hair, hung

on my bare skin

sunstruck and shimmering in

the salt-stunned air.

I had to endure

such heaviness; to push

upward against the rush

of riptide and current.

I said, I can’t

do this, but I

did it, and I

made it look natural

to float au naturel,

easy as the art

of swimming in salt

water, my pelvis fallopian,

eager, the shell scalloped,

the shell’s translucent pink

a flat-out Freudian wink.

Did you think that

the shell beached itself? That

a breeze as soft

as a hand luffed

my long hair and

breathed me onto land?

And when I reached

shore, I yanked leeches

from my legs, dredged

sand from armpits, cadged

food from scavenging birds.

I learned the words

I would need here.

Learned want, learned fear

and how to live

with both. (How? Forgive

yourself for being mortal.)

Myth is the portal

through which we pass,

becoming human at last,

rising out of dream

and desire to realms

of reality, where love,

a woman, by Jove,

survives, strong and free,

engendering her own destiny.

In her interpretation of the poem, Victoria writes,

Often, society presents women as one of two extremes, extremes that are still inaccurate, generalized, non-dimensional representations. In employing the goddess type as the foundational metaphor in her poem, Cherry reclaims this type as her own, transforming it into a positive through poetry. In “Rising Venus,” the goddess is no longer the passive object of masculine infatuation, but a dynamic victor that enables her own survival and achieves her own fulfillment as an individual. The title of Cherry’s poem also alludes to Botticelli’s painting The Birth of Venus. This male-created portrait of Venus idealizes her. Botticelli painted Venus into being, giving her a lush, curvaceous body. Her skin is porcelain perfection, and most of it is exposed, spare the breast covered by her hand and her genitalia covered by a ribbon of her golden, flowing hair. When we compare this renowned, male-created representation of Venus with the representation of Venus that Cherry presents in her poem, we see how Cherry writes to reconstruct this representation of Venus and infuse it with meaning relevant to women’s actual lived experiences as opposed to mythologies about those experiences.

By titling her poem “Rising Venus,” Cherry suggests that perhaps the goddess Venus, serving as a collective image representative of all women, is the speaker. Cherry begins “Rising Venus” with the line “They have it wrong.” This bold statement immediately allows the poem’s female, first-person speaker to assert her true voice to correct the wrongs, to utilize her voice throughout the poem to define herself rather than accept the falsities bestowed upon her by the “they.” Though the poem never reveals the specific identity of the “they,” the text suggests “they” is anyone who ever sought to define the speaker in anything other than her own terms. Thus, the first line of the poem is an act of reclamation. In the second line of the poem, the speaker offers a correction: “I am not young.” In intimate first-person, the speaker states what she is not, then, in the following stanzas, states what she is: “born old enough / to ride the rough / waves of the sea / without drowning, and immodestly.” This striking image of a timeless woman tangibly depicts a speaker as a shameless speaker dominating the seemingly uncontrollable element of the sea. This image shows the speaker is more than she seems; she is capable and self-assured, and choosing to present herself in such a way. The rest of the poem continues in a type of descriptive narrative through which the speaker tells her story, building it up by overcoming obstacles, and ultimately establishes herself as empowered victor, goddess, woman.

And here is Victoria describing the workshops that she set up:

Each workshop loosely adhered to the following structure: introductions, initial discussion, reading of the poem, creative response to the poem, and concluding discussion (in which we viewed the creative works we produced and recognized their function as types of self-portraits in and of themselves). Each workshop ranged from an hour and fifteen minutes to about two hours, depending on the amount of time spent on discussion and creating works.

In her presentation, Victoria showed us some of the art that the workshop participants created. Here are descriptions of two of them:

–One participant drew a comic strip of herself as the Rising Venus. She titled the strip “& again,” revealing that the comic represented a cycle. The comic included three panels: the first one, in which water covered all but the top of the head of the figure, the second one, in which the figure rose up fully above the water in a victorious stance, and the third one, in which the goddess was slipping, falling back into the water. The participant spoke about how this cyclical comic showed her own struggles, how, just when she felt confident and secure in her life choices, she would slip and fall and the cycle would start again.

–[Another] participant portrayed herself as goddess in an artwork that expressed what she has overcome and dredged from herself. The creative work shows the figure standing exposed on the beach, as objects she has dredged from herself flow down from her and litter the sand. This participant stated the things she has dredged have been positive and negative. She pointed out the things she dredged from herself often included other’s expectations or standards, and how, while they were not always bad, they were not her own expectations and standards for herself. This participant talked about her personal struggle dealing with things she thought she needed to change about herself because they were things others thought she needed to change about herself. She stated that she overcame those outside expectations and has worked and is continuing to work to find what she wants for herself.

Victoria found a way to use literature, which had aided her in her own healing process, to help others. I was left saying, “Wow!”