Friday

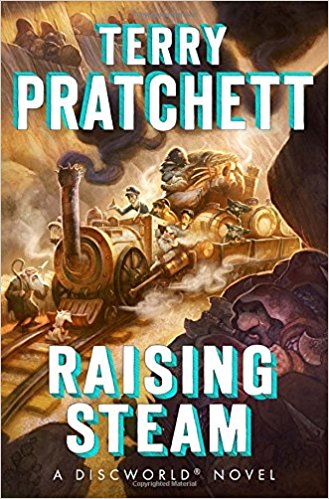

For a while now my fantasy literature students have been badgering me to read Terry Pratchett, so I finally checked out Raising Steam (2014) on disk, and Julia and I listened to it on our 12-hour trip down to Tennessee. I now understand why millennials respond to Pratchett as they do: his fiction captures the excitement and the energy of our post-modern, multicultural world.

What with the rise of ISIS, Brexit, Donald Trump, and various authoritarian regimes, it sometimes appears that liberal values are on the defense. It is indeed the case that reactionary forces have gained traction in recent years. Raising Steam reminds us, however, that the future has far more to offer than the past.

Discworld, the setting for Pratchett’s 40 novels, is a fantasy world inhabited by witches, trolls, goblins, gnomes, dwarfs, wizards, golems, vampires, werewolves, pixies, humans, and others. Instead of battling it out a la Tolkien, however, they are gradually learning to live together. This is no mean feat since they live on different planes of reality, but the world is a much more interesting place because of them. Furthermore, privileged species gradually discover that others have hidden talents. Goblins, once regarded as vermin, prove to be geniuses around machinery.

Not everyone is tolerant of diversity, however, and fundamentalist dwarfs are trying to rekindle their race’s traditional hatred of trolls. Clearly a stand-in for ISIS ideologues and the like, they target fellow dwarfs that collaborate with other species, thereby (so the radicals contend) violating the tenets of their god Tak. The fundamentalists also oppose modernity, seeking to sabotage and destroy the new telegraph and railway systems.

For those accustomed to sword and sorcery fantasies, the introduction of a steam engine may seem discordant, but Pratchett knows what he’s doing. Fantasy, I regularly tell my students, is always oppositional, defined against something rather than a thing in itself. When Tolkien created his fantasy as an escape from the horrors of World War I, he imagined a pre-gunpowder, pre-engine civilization. His dream of an idyllic rural England, however, has plenty of technology (swords, elaborate fortresses, water mills). It’s just 12th century technology.

Since Tolkien’s day, the world has gone cyber, which means that 19th-century technology–technology that one can touch and see–now has some of the same oppositional glamor that swords once had. This accounts for the popularity of Victorian steam punk fantasy.

Pratchett has fun imagining the excitement that the railway once generated, and then he merges that excitement with the civil rights movements. Intolerance of emerging technology and intolerance of other species are retrograde positions. Pratchett makes clear that the world is a far more interesting place when all the races intermingle and when human inventiveness–or rather human, goblin, troll, pixie, etc. inventiveness–are allowed full throttle. Immigration and diversity rejuvenate moribund societies.

This is the message that gets preached towards the end of the novel after level-headed dwarfs thwart an attempted fundamentalist coup. One of them says that the purists, in their hatred of stone-manufactured trolls, have misunderstood the injunction of the dwarf god Tak:

Tak did not expect the stone to have life, but when it did, he smiled upon it, saying “All Things Strive.” Time and time again the last testament of Tak has been stolen in a pathetic attempt to kill the nascent future at birth, and this is not only an untruth. It is a blasphemy!

In addition to including Victorian-era technology, Pratchett also violates another tenet of traditional fantasy: his stories are comic. Contrast this with Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, and all those others who take fantasy very seriously. (I can think of only a few exceptions outside of Pratchett but some of them are classics, like The Princess Bride and Howl’s Moving Castle.) I attended a session at the recent International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts conference on “Fantasy and Comedy,” and one panelist observed that Pratchett received far fewer literary awards than he deserved. After all, if fantasy lit awards committees are already defensive about elevating a “children’s genre,” then adding comedy seems like another black mark. The speaker noted that Douglas Adams of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series has also been underrated.

Pratchett counters such naysayers by investing comic word play with the same creative energy that he does his fantasy world, with language seeming no less magical than mail-carrier werewolves (effective since they can switch from four legs to two and back) and golem horses that never get tired. For a sample of Pratchett’s humor, check out his handling of old codgers who grumble about “new-fangled ideas” like the railway:

[Moist Von Lipwig] ventured to wonder if they ever thought back to when things were just old-fangled or not fangled at all as against the modern day when fangled had reached its apogee. Fangling was indeed, he thought, here to stay. Then he wondered: “had anyone ever thought of themselves as a fangler?”

Pratchett’s joyous inventiveness carries all before him, making it clear that embracing change and diversity is hip. Why attempt to make America white again or restore the medieval caliphate or break England away from Europe when you could have Discworld instead? Pratchett’s millennial fans know what they’re about.

Further thought: The reason why comedy seems at odds with fantasy is because, when we enter a fantasy world, we often sense that we are treading upon hallowed ground. Mysterious parts of ourselves are put into play–we touch dream states–just as we do in religious ceremonies. Comedy, which seems to come from the head more than from the heart, can seem out of place. But laughter is holy in its own special way.