Pentecost Sunday

Christians today celebrate the arrival of the Holy Spirit, the “advocate” with God that Christ promised would be sent to his followers after he himself departed. Many poets, most notably John Milton, have seen the Holy Spirit as a poetic muse, which is how Denise Levertov regards it in her poem about the early British poet Caedmon. St. Bede’s account of Caedmon learning the gift of song goes as follows (I quote from Wikipedia):

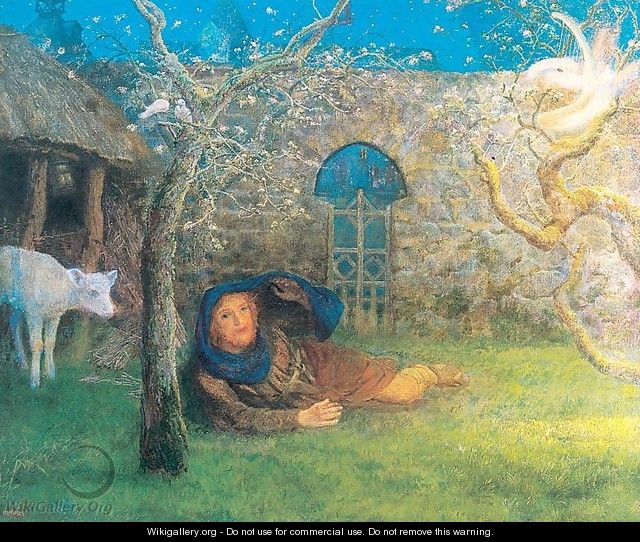

Cædmon was a lay brother who cared for the animals at the monastery Streonæshalch (now known as Whitby Abbey). One evening, while the monks were feasting, singing, and playing a harp, Cædmon left early to sleep with the animals because he knew no songs. The impression clearly given by St. Bede is that he lacked the knowledge of how to compose the lyrics to songs. While asleep, he had a dream in which “someone” (quidam) approached him and asked him to sing principium creaturarum, “the beginning of created things.” After first refusing to sing, Cædmon subsequently produced a short eulogistic poem praising God, the Creator of heaven and earth.

In her poem, Levertov draws on imagery from Luke’s account of Pentecost, especially the disciples speaking in tongues and a tongue of fire resting on each of them:

When the day of Pentecost had come, the disciples were all together in one place. And suddenly from heaven there came a sound like the rush of a violent wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared among them, and a tongue rested on each of them. All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability.

As a poet, Levertov identifies with the moment where Caedmon has his voice pulled from him. Initially he feels awkward and retreats to the dumb world of animals. The light from his rush torch, however, anticipates the inspiration that is to come:

I’d see by a twist

of lit rush the motes

of gold moving

from shadow to shadow

slow in the wake

of deep untroubled sighs.

Then suddenly the spirit moves within him, sending down holy fire that touches his lips and scorches his tongue. Levertov could be talking here of her own poetry and also her conversion to Christianity. Although the animals around don’t react to this burning moment–it can be invisible to all those around–Caedmon himself suddenly feels pulled into “the ring of the dance.”

Caedmon

By Denise Levertov

All others talked as if

talk were a dance.

Clodhopper I, with clumsy feet

would break the gliding ring.

Early I learned to

hunch myself

close by the door:

then when the talk began

I’d wipe my

mouth and wend

unnoticed back to the barn

to be with the warm beasts,

dumb among body sounds

of the simple ones.

I’d see by a twist

of lit rush the motes

of gold moving

from shadow to shadow

slow in the wake

of deep untroubled sighs.

The cows

munched or stirred or were still. I

was at home and lonely,

both in good measure. Until

the sudden angel affrighted me—light effacing

my feeble beam,

a forest of torches, feathers of flame, sparks upflying:

but the cows as before

were calm, and nothing was burning,

nothing but I, as that hand of fire

touched my lips and scorched my tongue

and pulled my voice

into the ring of the dance.