Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and I will send it/them to you. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

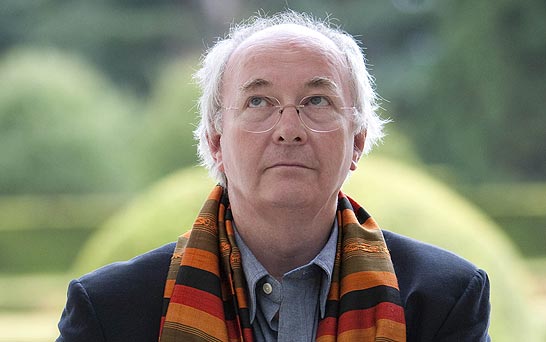

In anticipation of Philip Pullman’s final installment of his Book of Dust trilogy, scheduled to come out in September (if he can pull it off), I’ve been rereading The Secret Commonwealth. Because of all that has happened politically since I first read it three years ago, I’m even more chilled by his description of the church organization that runs things.

What has changed has partly been the takeover of the Supreme Court by Catholic extremists, although that shift has also been accompanied by the increasingly strident language of Christian White nationalists. And then there have been the book bans, the virulent attacks on transexuals, the rise of antisemitism, and mass shootings by White terrorists. White nationalists like Marjorie Taylor Green and Jim Jordan are also calling the shots in the House of Representatives. All of this was playing in the back of my mind as I read a speech given before the Magisterium, an organization consisting of the different entities in charge of the church.

Like our own Christian nationalists, the Prefect believes people of faith are under attack. A sense of grievance and resentment pervades his remarks.

“Brothers and Sisters,” the Prefect began, “in the name and the authority of the Most High, we are summoned here today to discuss a matter of burning importance. Our faith has in recent years been challenged and threatened as never before. Heresy is flourishing, blasphemy goes unpunished, the very doctrines that have led us through two thousand years are being openly mocked in every land. This is a time for people of faith to draw together and make our voices heard with unmistakable force.

This initial defensiveness, however, then gives way to a sense of opportunity. Now is the time to start imposing our will on others:

“And at the same time, there is opening to us in the east an opportunity so rich and promising as to raise the heart of the most despondent. We have a chance to increase our influence and bring our power to bear on all those who have resisted and are still resisting the good influence of the Holy Magisterium.”

Having moved from victimhood to power fantasies, the Prefect then—and oh so logically— delivers the solution. Democracy, he declares, must give way to what the communists used to call the vanguard, which supposedly will speak for the whole:

“In bringing you this news—and you shall hear much more later—I must also urge you all to pray most earnestly for the wisdom we shall need in order to deal with the new situation. And the first question I must put before you is this: Our ancient body, here represented by fifty-three men and women of the utmost faith and probity—is it too large? Are there simply too many of us to make rapid decisions and act with force and effect? Should we not consider the benefits that would flow from delegating matters of great policy to a smaller, a more swift-moving and decisive council, which could provide the leadership that is so necessary in these distracted times.”

The Prefect, it so happens, is delivering someone else’s script, just as Russian president Dimitri Medvedev used to do for Vladimir Putin. The puppet master in this case is Marcel Delamare, who heads the nefarious League for the Instauration of the Holy Purpose, which sounds a bit like the Catholic Opus Dei:

No one would ever know, but he himself had written the speech for the Prefect to deliver; and he had made sure, by private inquiry, by blackmail, by bribery, by flattery, by threat, that the motion to elect a smaller council would be passed, and he had already decided who should be elected to it, and who should chair it.

Later, moving from the bad guys to the good, we get an explanation about why it’s so hard to fight against fanatics. Fardar Corman is a wise elder of the wandering gyptians:

The other side’s got an energy that our side en’t got. Comes from their certainty about being right. If you got that certainty, you’ll be willing to do anything to bring about the end you want. It’s the oldest human problem, Lyra, an’ it’s the difference between good and evil. Evil can be unscrupulous and good can’t. Evil has nothing to top it doing what it wants, while good has one hand tied behind its back. To do the things it needs to do to win, it’s have to become evil to do ’em.

This is always the struggle between democracy and autocracy. As we’ve learned over the past seven years, we can never take the Constitution for granted.