Friday

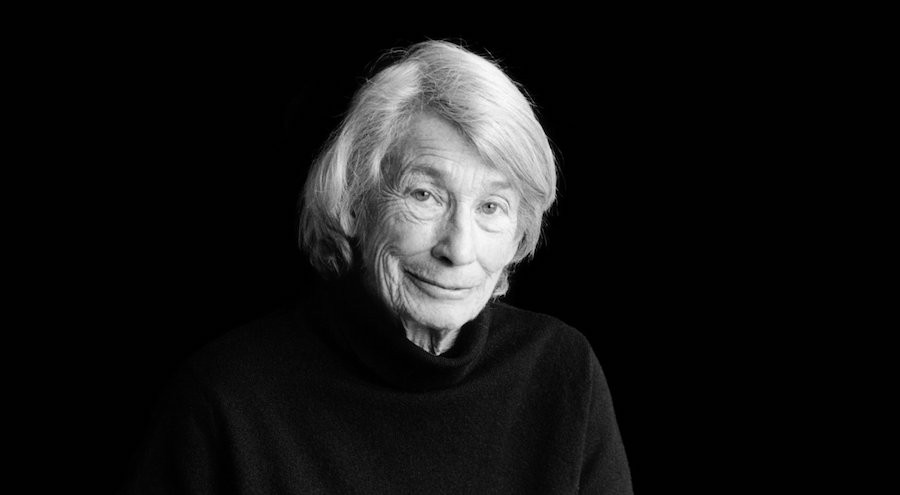

Mary Oliver, who died yesterday, may have been America’s favorite poet. I taught her Pulitzer Prize-winning American Primitive for over 20 years in a nature-focused Introduction to Literature class and so have seen up close her impact on readers. When death has entered my own life, I have often turned to Oliver’s poetry.

For instance, I revisited “University Hospital, Boston” when my best friend Rachel Kranz lay dying in a Bronx hospital. I read “In Blackwater Woods” at the memorial service of my beloved colleague Kate Chandler, who loved Oliver’s poetry. And the night after my oldest son Justin drowned, I hung on for dear life to two lines from Oliver’s “Lost Children,” although I didn’t know at the time where the lines came from.

I therefore devote today’s essay to some of Oliver’s views of death, especially as expressed in American Primitive, the poems I know the best. In “In the Pinewoods, Crows and Owl,” death is a fearsome force, lurking in the darkness while we, like the crows, obsess over it endlessly. Addressing the owl/death as “the bone-crushing prince of dark days,” she writes, “You/ are the key to everything while they fly/morning after morning against the shut doors.” Then she adds, “You/ will have a slow life, and eat them, one by one.”

In “University Hospital” she describes loss as “a place of parched and broken trees,” and in “Blossom” she writes that “time/ chops at us all like an iron/hoe” and that “death/is a state of paralysis.”

Yet “Blossom” also points to something beyond individual death—“we are more than blood,” she writes–and in “The Fish” she follows this up by looking at the bigger picture. After describing the painful death of a fish, which she catches and eats, she describes the cycle of life:

Now the sea

is in me: I am the fish, the fish

glitters in me; we are

risen, tangled together, certain to fall

back to the sea. Out of pain,

and pain, and more pain

we feed this feverish plot, we are nourished

by the mystery.

At this point, life and death are less an individual tragedy and more a grand mystery. This growing realization helps account for her equanimity at the end of “In Blackwater Woods,” where the fires of life and “the black river of loss” roll back and forth in a drama “whose meaning/none of us will ever know”:

Every year

everything

I have ever learned

in my lifetime

leads back to this: the fires

and the black river of loss

whose other side

is salvation,

whose meaning

none of us will ever know.

To live in this world

you must be able to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it:

and, when the times comes to let it go,

to let it go.

I do not know how Oliver responded to her death when it finally came to her—lymphoma carried her off at 83—but her acknowledging that she would one day die caused her to live life as fully as she could. In “When Death Comes,” she is resolved to follow the advice of her fellow Massachusetts author Henry David Thoreau, who in Walden writes,

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

Or as Oliver puts it, “When it’s over, I want to say all my life/ I was a bride married to amazement”:

When Death Comes

When death comes

like the hungry bear in autumn;

when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse

to buy me, and snaps the purse shut;

when death comes

like the measle-pox

when death comes

like an iceberg between the shoulder blades,

I want to step through the door full of curiosity,

wondering:

What is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?

And therefore I look upon everything

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood,

and I look upon time as no more than an idea,

and I consider eternity as another possibility,

and I think of each life as a flower, as common

as a field daisy, and as singular,

and each name a comfortable music in the mouth,

tending, as all music does, toward silence

and each body a lion of courage, and something

precious to the earth.

When it’s over, I want to say all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened,

or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world

I pray that Oliver stepped through that door full of curiosity. I can’t imagine her not having done so.