Wednesday

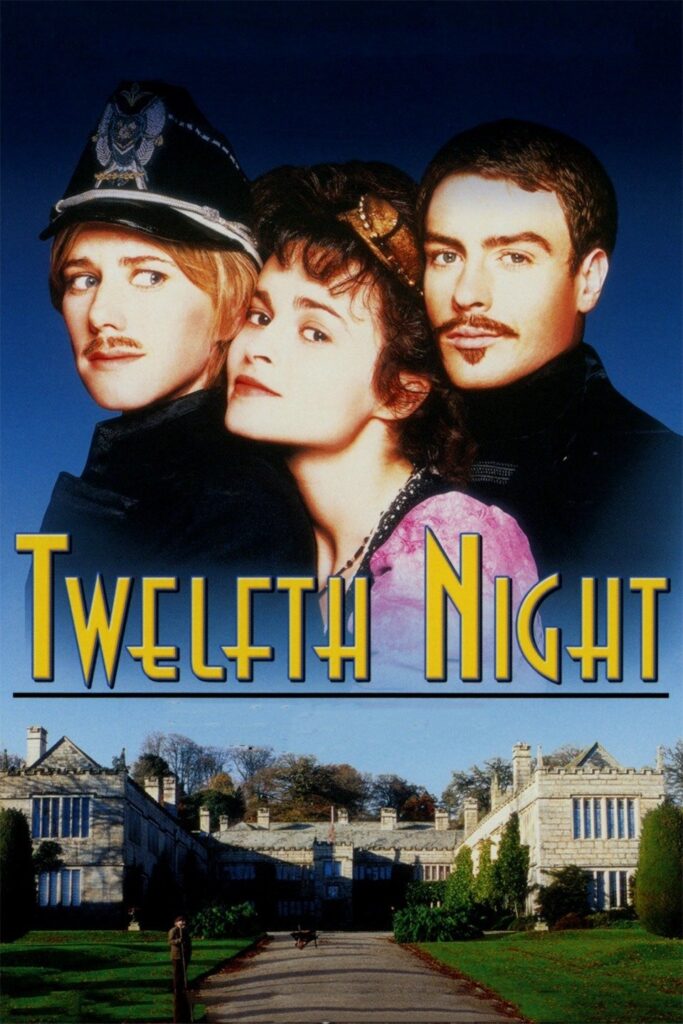

After a full day of revision conferences with my “Composition and Literature” students, I report today (with the students’ permission) on their ideas about Twelfth Night. Tomorrow I’ll share the ideas of those writing about Othello, the other essay option. As you will see, my students are hungry for authentic relationships and see in Shakespeare’s 1601 comedy guidelines for achieving them.

To give you a quick overview of the play, Viola is separated from her twin brother Sebastian in a storm, which each thinking the other is dead. After she disguises herself as a man (Cesario) so that she can work for Count Orsino, the count comes to appreciate her/him and appoints her/him as emissary in his wooing of the Lady Olivia. Olivia instead falls in love with Viola/Cesario, who in turn is in love with Orsino, making for an impossible situation. All ends well, however: after a series of comic misunderstandings, Orsino marries Viola while Olivia marries Sebastian, who looks just like his sister.

Three other characters show up in the student essays: Sebastian’s friend Antonio (who has a homosexual crush on Sebastian), Olivia’s uptight steward Malvolio, and Olivia’s jester Feste.

Sidney was fascinated by the Sebastian-Antonio relationship, which she then compared with the Olivia-Viola relationship. Both Sebastian and Olivia find themselves worshipped (Sebastian by Antonio, Olivia by Orsino) and experience their pedestal position as traps. After all, when someone worships you, he (or she) wants to possess you in their idealization of you. As Sidney put it, neither Sebastian nor Lady Olivia feel “seen” by the people who profess to love them.

As a result, both keep their distance, with Sebastian attempting to leave Antonio and Lady Olivia rejecting the advances of Count Orsino. Viola, on the other hand, sees Olivia as a human being, not as an angel, and Olivia finds this exhilarating. As Sidney put it, “It’s a breath of fresh air to Olivia. Someone’s finally having genuine conversations with her, challenging her, and being honest with her.” Reminding me somewhat Aristotle in his discussion of friendship (in Nicomachean Ethics), Sidney concluded that true friendship—the kind of friendship she wants—consists of honoring the other in the fullness of his or her individuality.

Laney thought similarly except that, in her case, she compared Viola with Lady Olivia’s fool Feste. Both, she argued, rejuvenate a society that is hung up on static role playing. Lady Olivia feels that, to be a perfect lady, she must mourn her late brother for seven years before she accepts marriage proposals. Feste and Viola, by contrast, want people to live and love. Feste uses humor to loosen Olivia up, after which Viola presents her with an alternative way to live life: take risks and follow your heart. As a result of this encounter, Olivia abandons her former resolve and goes running after Viola, whom she thinks is a man.

For her part, Grace saw Viola pushing against a similar stasis as that described by Laney, only Grace saw gender stereotypes at work. In this world, men feel they have to be stereotypically male (hard and emotionless), women stereotypically female (angelic and ultra-sensitive). Orsino and Olivia both come to see these gendered roles as traps, with Orsino longing to access his female side and Olivia her male side. Both fall in love with Viola/Cesario because she seems able to balance male-female: she is sensitive (which Orsino appreciates because he can talk to her/him about feelings) and enterprising (she launches herself into the world rather than looking for a man to protect her). Grace noted that men and women, even today, find themselves trapped in stereotypical gender behavior, and she appreciated how Shakespeare shows us a way out.

Finally, there was Hayden’s essay on the necessity of comedy in the world. We get in trouble, Hayden contended, when we get hung up on life’s seriousness. When Olivia decides to mourn her brother’s death for seven years, thereby depriving the world of a potentially vibrant woman, she has the approval of Malvolio but not of Feste. Feste makes a joke that helps return her to the world of living relationships:

Feste: Good madonna, why mournest thou?

Olivia: Good fool, for my brother’s death.

Feste: I think his soul is in hell, madonna.

Olivia: I know his soul is in heaven, fool.

Feste: The more fool, madonna, to mourn for your brother’s soul being in heaven. Take away the fool, gentlemen.

When Olivia asks Malvolio for his opinion, he disapproves of what he regards as a frivolous approach to life:

I marvel your ladyship takes delight in such a barren rascal: I saw him put down the other day with an ordinary fool that has no more brain than a stone. Look you now, he’s out of his guard already; unless you laugh and minister occasion to him, he is gagged. I protest, I take these wise men, that crow so at these set kind of fools, no better than the fools’ zanies.

To which Olivia replies:

Oh, you are sick of self-love, Malvolio, and taste with a distempered appetite. To be generous, guiltless and of free disposition, is to take those things for bird-bolts that you deem cannon-bullets: there is no slander in an allowed fool, though he do

nothing but rail…

Olivia is on her way to reconnecting with life and love. As Laney and Grace argue, she needs only Viola to complete the transition.

Malvolio, by contrast, Hayden sees as beyond saving. When, through a prank played upon him by Twelfth Night revelers, he ends up (temporarily) in a madhouse, Hayden notes that the fool—disguised as a pedant—once again “tells someone exactly what they need to hear”:

Feste explains how Malvolio is ignorant when he says, “there is no darkness but ignorance” (IV ii). Feste is saying something more important than what it seems. He alludes to how Malvolio lives in ignorance and darkness because he is so serious all the time….In order for Malvolio to get out of his prison,…he must be able to see the comedy within life. If he cannot, then he will live the rest of his life in a metaphorical prison of being too serious.

Great literature connects us with our best selves. In their essays, I saw Sidney, Laney, Grace and Hayden seeking to articulate and to get in touch with these selves.