Thursday

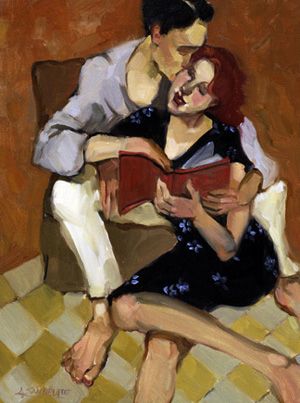

A year ago The Washington Post ran a heartwarming article about the marital possibilities in reading aloud. Jennifer Acker, an editor suffering from a brain disease that made it almost impossible for her to read, had to acquaint herself with several works for a panel she was moderating. In desperation, she asked her husband to read the works to her, sometimes over the phone from his work place. In the process, she fell in love with him all over again:

I’d never thought much about my husband’s voice. I knew its Minnesota flatness in the o’s and a’s, and I could recall, instantly, the influence of his immigrant parents: Indian-British formulations like taking exercise and mangled Gujarati phrases. But knowing these things did not equal the spell cast by his cadence and timbre as he read to me.

For the first time, it seemed, I noticed these qualities. A warmth that was never sticky or soft. His voice had range but did not jar with sharp peaks or scraping valleys. The Midwestern vowels came through, but were not distracting. At the end of the day’s story, I did not want to hang up the phone.

His voice was not one ripe for performance; I wouldn’t urge him to take up the stage or occupy a recording booth. It was simply a wonderful voice that allured me. Something I had known but could not have articulated, even after 14 years together. Reading to me, reading stories I had chosen because I needed to hear them, was an intimate act of devotion. It not only helped me with my work, but also allowed me to revel in a side of him I rarely observed. Here were moments both vulnerable and so revealing they proved with a force beyond all reason that I wanted him, all of him, and to be near him always.

The article got me thinking about reading aloud as a conjugal act, an activity that was common in the 19th century. George Eliot and George Henry Lewes, for instance, read Jane Austen’s Emma together while sitting under a tree, and there are reports of them reading Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s long poem Aurora Leigh to each other. I can imagine them reading many such works together in the evening before the fire.

This sounds far more meaningful than watching television together.

While Julia and I never read to each other, we used to read to our children every night and on long car rides. I associate Hatchet, Huckleberry Finn, and To Kill a Mockingbird with the twelve-hour trek to Tennessee. Now, of course, we would probably be listening to books on disk, or perhaps the kids would be watching movies or playing video games, just as families began listening to the radio and then watching television. Something precious has been lost.

When I mentioned Acker’s article to my brothers, David noted that the same can be said of piano playing. If the piano looms so large in Jane Austen novels, it’s because that would have been the only music readily available. The victrola would later change that situation.

There’s no reason we can’t start reading to each other again. My brother Sam read the Harry Potter books to his wife Elizabeth, who still has vivid memories of the experience. My friends Jackie and Alan Paskow, without television in their British Columbia summer cottage, would read long novels like War and Peace to each other and found that it enhanced their marriage.

Of course, it is no longer a novelty to hear books read aloud, what with books on disk. But Acker says that reading with a spouse is more intense:

[A]s he gave voice to the words, the architecture of the story fell into place. I felt bewildered when the narrator felt bewildered. I anticipated actions and enjoyed my expectations being subverted. Again the ending threw a subtle curveball, and we returned to earlier events and revelations. I was surprised by how firmly the story secured itself in my mind. Partly this is editorial training, but such deep impressions were not made by audiobooks, which entertained but were ephemeral. The impact came from the reading. His reading. His voice that had drawn me in, embraced me.

So if you want to spice up your relationship, try it out.