As I reread Northanger Abbey with my first year Jane Austen seminar, I am heartened to see that Austen endorses a reading program much like the one that my father followed with my brothers and me and that I followed with my sons: encourage your kids to read good literature and they will learn from it the life lessons that they need.

Austen is describing the reading tastes of her “unpromising” heroine. Anticipating Lewis Carroll, she notes that Catherine is “often inattentive, and occasionally stupid” when it comes to memorizing the didactic poems that parents considered proper for their children, such as “The Beggar’s Petition.” This 1766 Thomas Moss poem contains such florid passages as the following:

Dear tender pledges of my honest love,

On that bare bed behold your brother lie;

Three tedious days with pinching want he strove,

The fourth, I saw the helpless cherub die.

On the other hand, Austen tells us that Catherine “was not always stupid; she learnt the fable of “The Hare and Many Friends” as quickly as any girl in England.” This John Gay poem is a child-pleasing fable about false friends and, like many of Alice’s poems where she unintentionally butchers instructional verse, it contrasts with “The Beggar’s Petition” by having a grisly ending as Hare discovers that none of his so-called “friends” are willing to save him from the hunters. The emotions in the poem are true, not pious and sentimental.

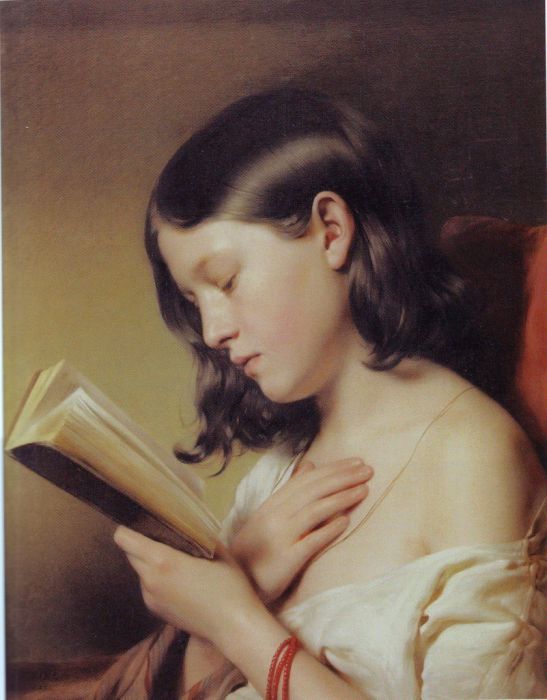

Much of Catherine’s learning occurs from the reading that she does on her own since her mother, although she cares about her children, “was so much occupied in lying-in and teaching the little ones, that her elder daughters were inevitably left to shift for themselves.” Catherine’s reading includes a fair amount of melodrama, which one would expect an adolescent to appreciate.

At the beginning of Alice in Wonderland, Carroll writes, “Once or twice [Alice] had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, ‘and what is the use of a book,’ thought Alice `without pictures or conversations?'” I think Carroll here must be channeling the following passage from Northanger Abbey:

[I]t was not very wonderful that Catherine, who had by nature nothing heroic about her, should prefer cricket, baseball, riding on horseback, and running about the country at the age of fourteen, to books–or at least books of information–for, provided that nothing like useful knowledge could be gained from them, provided they were all story and no reflection, she had never any objection to books at all.

When Catherine gets a little older, her reading interests broaden into what we would call “classic literature” but it’s clear that she’s still reading for pleasure:

[F]rom fifteen to seventeen she was in training for a heroine; she read all such works as heroines must read to supply their memories with those quotations which are so serviceable and so soothing in the vicissitudes of their eventful lives.

From Pope, she learnt to censure those who

“bear about the mockery of woe.”

[“Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady”]

From Gray, that

“Many a flower is born to blush unseen,

“And waste its fragrance on the desert air.”

[“Elegy on a Country Churchyard”]

From Thompson, that–

“It is a delightful task

“To teach the young idea how to shoot.”

[“The Seasons”]

And from Shakespeare she gained a great store of information—amongst the rest, that–

“Trifles light as air,

“Are, to the jealous, confirmation strong,

“As proofs of Holy Writ.”

[Othello]

That

“The poor beetle, which we tread upon,

“In corporal sufferance feels a pang as great

“As when a giant dies.”

[Measure for Measure]

And that a young woman in love always looks–

“like Patience on a monument

“Smiling at Grief.”

[Twelfth Night]

One can see why all these works would hold appeal for a teenager:

–Alexander Pope’s “Elegy of an Unfortunate Lady” is a tearjerker about a lady who commits suicide for love.

–Thomas Gray’s “Elegy on a Country Churchyard” is a heartfelt lament about those who lie buried and forgotten.

–James Thompson’s “The Seasons” is a lyrical hymn to nature.

–Shakespeare’s Othello is (of course) about jealous love, Measure for Measure is about the unjust oppression of lovers, and the passage from Twelfth Night is about Viola hiding her love from Orsino.

Austen will go on in Northanger Abbey to defend young people’s right to read novels (see my post here) rather than dull essays from The Spectator or tiresome histories and conduct manuals. Here she is showing the benefits of reading lyrical poetry and gripping drama.

Take note, you parents who want your children to grow up to be heroines (and heroes).

Go here to subscribe to the weekly newsletter summarizing the week’s posts. Your e-mail address will be kept confidential.