Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Tuesday

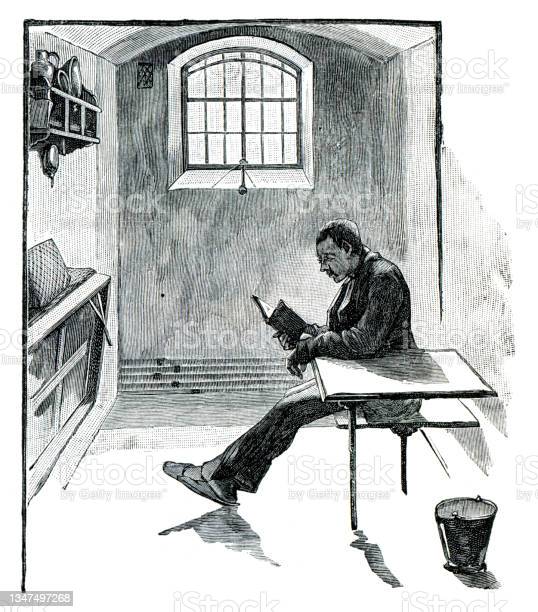

I’ve been reporting on a book that Oberlin librarian Valerie Hotchkiss sent me, an account by former dope addict and now writer Daniel Genis about how he read 1000 books (1046 to be exact) while serving a ten-year prison sentence. For the most part, literature proved a godsend although there were some notable exceptions. But first to some of the positives.

For instance, literature helped Genis handle solitary confinement, which he experienced four times while in prison:

Torture is not illegal in the United States; it is used with abandon every time a prisoner is put iin solitary. I had the escape route of a literary bent, which allowed me to spend my box bits in the castle turrets of [Mervyn Peake’s fantasy series] Gormenghast and the drawing rooms of [Thackeray’s] Vanity Fair and on the tennis courts of Infinite Jest. Most of the boxed population, however, was barely literate. To this day I can summon the shrieking and howling, punctuated by teenage madmen banging the walls with their foreheads, that was the accompaniment to my reading.

Not all literature proved to be equally useful, as he discovered when, as a prison job, he served meals and facilitated discussions amongst “a crew of honest-to-God monsters.” These were men with severe mental disabilities, some of whom had committed horrendous crimes but whom he came to love. Novels didn’t help him better understand them, however:

Many of the works I consulted dealt with neurotic malaises that poorly corresponded with the real-life examples with whom I was eating my meals. Robert Musil’s Man without Qualities meandered over the gradual erosion of a sense of self, while The Brothers Karamazov explored murderous rages and how one can come to them quite rationally. Crime and Punishment provided the best justification for murder ever penned, and anyone who is convinced by its conclusion, and Raskolnikov’s inability to live with the crime, is too easily cajoled. I read de Sade to try to understand if there was truly any aesthetic to evil, and followed that up with Michel Houellebecq’s Elementary Particles. The French author made an argument for the humanity and even nobility of perversion. Antonin Artaud tried to do the same for cruelty, and the foibles of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi made a mocking sense of madness and evil that was delightful to read about but utterly unnerving when it was housed in the cell next to yours. The truth is that these sophisticated interrogations of psychosis provided little illumination regarding the mentally ill men around me. These were men who cut off the ears of their kidnapped victims rather than their own.

Genis mentions one book that got closer to the truth:

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Next was a more accurate look into the world in which I was living, with its simpleminded obsessions, petty cruelties of the orderlies, and horror for the person with moments of lucidity interspersed with his blessed madness.

Fortunately, literature reminded Genis of the importance of humor and helped him hold on to a sense of play. As he notes, during his ten years in prison he “laughed as much as possible, feeling that every chuckle was a moment stolen back from the Department of Corrections.” He said he picked up the idea from Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago,

where the innocent prisoners laugh at political jokes that are treacherous because of the informants all around, but laugh nevertheless to remind themselves that they are more than just zeks. Central European, as well as German, literature is remarkably suited to jailhouse reading. They have a native sense of absurdity, a condition I walked around in for years. Having seen men attempt suicide in toilet bowls and murders committed a dozen feet from me, what could I do but put on the same sardonic smile that I imagine Bruno Schulz wore when his brilliant brains were blown out by a callous SS officer. I loved his Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass….Perhaps it was the blood that soaked the soil of these authors’ heimland, but I also adored Hermann Hesse, especially The Glass Bead Game, better titled in the original as Das Glasperlenspiel. German writing on man and his place in this ungainly life of ours appealed to me when I was so lost in this one. Kafka’s Castle, with its cruel absurdities and nightmare bureaucracies, felt like an apt metaphor for prison life. I went further down this rabbit hole and discovered other Czech literature to revel in. Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk taught me how to laugh off the world life has to offer. Karel Čapek’s War with the Newts suggested that any oppressed underclass has a certain power.

But this sense of humor, which literature helped keep alive, also got Genis into trouble. Tomorrow I’ll share how a harmless joke, inspired by Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus and Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls, led to Genis being locked up in solitary confinement for 90 days.