Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and I will send it/them to you. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

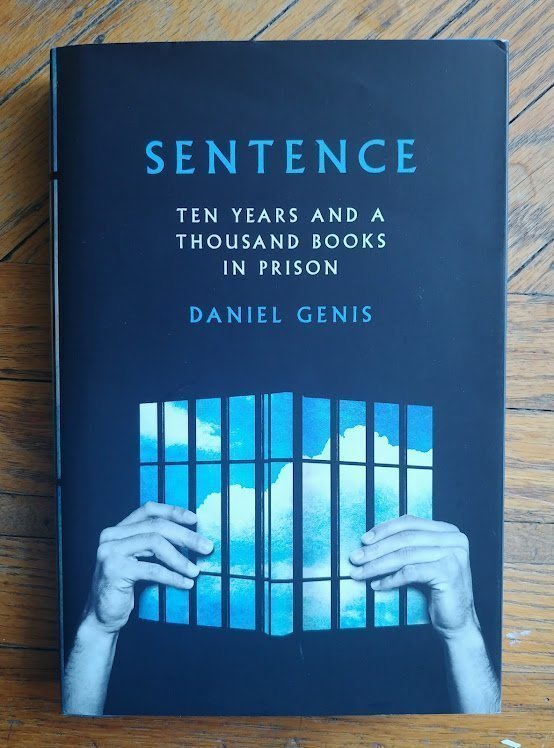

Someone—sadly I can’t remember who—gave me a copy of Daniel Genis’s Sentence: Ten Years and a Thousand Books in Prison, about a man who used books to cope with a ten-year prison sentence. The son of a Soviet émigré and an NYU graduate, Genis was an unlikely felon, but a ferocious drug habit turned him into an armed robber. And although he was never truly dangerous—he used to apologize to his victims—he was arrested outside of a Barnes and Noble, where he had just stolen a book, and sentenced to 12 years (two years off if he behaved). The judge, in giving out the harsh sentence, said he was someone who should have known better.

While Genis’s observations of prison life are themselves compelling and enlightening, I of course am particularly interested in his use of literature. I’m only a fourth of my way through the book—I’ll report on the whole when I finish—so today I’m going to quote a few passages to give you a sense of the role that books played. Sometimes they provided an important perspective, sometimes they gave him special insight, sometimes they provided important identity narratives, and sometimes they were used to avoid facing up to reality.

Certain books appear to have had the power to lead Genis astray:

[Luc Santé’s 1917] Low Life was exactly the type of book that had led me to this juncture. My love of obscure tales, printed artifacts from a city devoted to words, and the seamier side of the past primed me to become a bookish New York junkie with my head in the opium clouds of the 19th century….Villainy in sepia attracted me. I relished the idea that I was copping dope on the same blocks that William Burroughs had when he lived in his Bowery bunker; I had read Junkie several times by then, more as a users’ manual than a work of art. Delving deeper, I read the only published collection of Herbert Huncke’s mediocre work when the ancient dope fiend was still alive, and I lived for the streetscapes described in biographies of Beat Generation figures because they were my streets, too.

Some books were used to escape reality:

Of course, when things got a little too real and I found myself on Rikers Island, I lost my taste for the gritty and retreated into science fiction. On the day of my sentencing, I read William Gibson’s Neuromancer twice in a row to avoid contemplating what awaited me.

Some books, these ones creative non-fiction, helped Genis frame the experience:

When I look back, my extensive reading of the travelogues of nineteenth-century explorers was how I sought succor on my own trip through the Incarcerated Nation. I read James Boswell’s Journey to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson and Evelryn Waugh’s collected travel writing, as well as Paul Theroux, Ryszard Kapuscinski, and other genteel travelers, but it was Richard Burton’s Pilgrimage to Mecca and Henry Stanley’s Through the Dark Continent with which I most identified….[A]s I moved through the treacherous terrain of the state’s penal system, I took my own versions of notes on the varieties of human experience little known in the outside world.

Some fictions played a key role in holding onto a sense of self:

I made sure not to forget who I was before I became prisoner 04A3328. This was a common theme in the literature of prison. Henry Charrière relied on his butterfly tattoo to survive the challenge in Papillon. Jean Valjean’s torment over becoming #24601 in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables was clarified for me by my struggle to remain Daniel Genis and not the 3,328th prisoner to be processed into New York State prison in the year 2004. I had read Les Mis years before but returned to it for the description of its hero’s decades of confinement and escape.

Sometimes lit helped him process what he was experiencing:

The fact that much worse than I experienced was suffered by innocent people in The Drowned and the Saved [Primo Levi’s account of being processed into a death camp of Jews by Nazis] made my flicker of self-pity laughable, but much of what I read in the books of the German and Russian camp life was familiar. Downstate Correctional Facility was an hour north of New York. It was like the Sorting Hat in the Harry Potter books, though I guess we all went to Slytherin. Being the first prison that a convict sees, it had a processing procedure that was conducted with barked orders, insults, and even occasional violence; Elie Wiesel described something like it in Night, so I knew that such abuse was deliberate…. We were being checked for defiance.

Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” operates in prison but more, Genis explains, as a clenched fist:

Inside, the invisible hand of the market was naked and visible. In the Malthusian competition of all against everyone, the allegorical hand often functioned a clenched fist. Dostoyevsky’s House of the Dead describes nineteenth-century czarist prisons in a similar way. One can purchase so much in a prison yard.

Some of the books that Genis describes as escapist are existential nightmares in the form of spy novels and noir science fiction, works that speak to his prison conditions:

Much of my reading during my time on Rikers was meant to distance myself from my present reality. Life felt so hopeless, and the light at the end of the tunnel was impossibly far away, so I really preferred reading of the escapist variety rather than literary challenges. After all, literature inevitably reveals truths about our sordid lives, like the famous “naked lunch”—when you can finally see what’s on your fork. That was pretty much the last thing anyone facing a chunk of hard time would want, so I reread all of William Gibson and lots of Philip K. Dick and John le Carré.

And then some works described the reality he was witnessing:

Prison was populated mostly by drug addicts, with the mentally ill thrown in (Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was as helpful to me as the cavalcade of prison memoirs I plowed through), as well as a number of guys too violent to adhere to the social contract.

When guards became suspicious because of his speaking Russian with his mother over the phone, he found himself thrilling to Cold War spy novels:

Being apprehended and revealed as a bilingual was the closest I ever felt to the KGB sleeper agents I read about in John le Carré novels.

The fantasy of Cold War operatives seeded in the suburbs speaking KGB-taught English, was exciting for me. I read Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and others in the genre. I looked for more of the same in Tom Clancy books but didn’t find it. Instead Len Deighton’s Ipcress File and Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana and The Comedians filled my need to read about being out of place with a purpose. I loved The Day of the Jackal and Six Days of the Condor and put them on the list of movies I wanted to watch when I got out.

One often doesn’t know, ahead of time, which books one needs for a situation. That is how literature differs from the how-to genre. But read enough fiction and you’ll find the books that speak to your condition. And that will help you find a way through it.