Thursday

Teaching Philip Pullman’s Subtle Knife, the second volume of his Dark Materials trilogy, has me thinking of how I used reading to negotiate the end of my childhood innocence. Pullman’s target, as I explain here, is the church, which according to him fetishizes innocence and uses adult sin as a money maker. You can read in that post how I see Pullman’s view of religion as one-dimensional, but today I reflect upon my adolescent self.

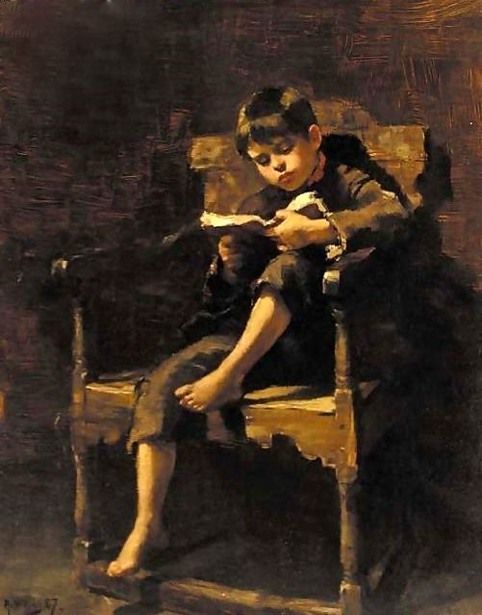

As a child, I did not want to grow up. Segregated Tennessee seemed like a bleak and uninviting place—I grew up amidst contentious civil rights battles—so I retreated into fantasy. Above all, I wanted to join the fellowship of the ring. Few books before or since have impacted me as forcefully as Tolkien’s trilogy.

In choosing that work, it was in tune with the author. Tolkein’s fantasy germinated in his own desire to escape, in his case the horrors of World War I trench warfare, which he witnessed close up.

My English teachers, however, insisted that I read more adult fare. If Lord of the Rings topped the works that I loved, Catcher in the Rye topped the list of those I loathed. I hated everything about it–Holden’s interactions with his fellow students, his swearing, his smoking, his running off to New York, his encounter with the prostitute and her pimp. I felt soiled.

Years later, knowing that our most intense reading experiences tell us much about ourselves, I returned to Salinger’s classic. Imagine my shock when I discovered that my resistance to growing up is the central theme of the novel. You know the passage, which involves his 10-year-old little sister, whom Holden adores:

“You know what I’d like to be?” I said. “You know what I’d like to be? I mean if I had my goddam choice?”

“What? Stop swearing.”

“You know that song ‘If a body catch a body comin’ through the rye’? I’d like–”

“It’s ‘If a body meet a body coming through the rye’!” old Phoebe said. “It’s a poem. By Robert Burns.”

“I know it’s a poem by Robert Burns.”

She was right, though. It is “If a body meet a body coming through the rye.” I didn’t know it then, though.

“I thought it was ‘If a body catch a body,'” I said. “Anyway, I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around–nobody big, I mean–except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff–I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be. I know it’s crazy.”

Of course, Holden is projecting here. He wants someone to catch him. He wants to go back to an innocent time before he became a confused adolescent, a time when his brother was still alive. He responds to his fears and anxieties by acting up.

I too was projecting. I hated the novel because it exposed to me my own inner turmoil. I identified too closely with Holden.

So what did I do? Sartre and Camus afforded me a compromise. On the one hand, they told stories that were enough like parables that they felt like literature, not life. (Salinger felt like raw life.) On the other hand, they dealt with concerns that seemed Adult. I felt at a safe remove from life, even as a gingerly dipped my toe in it. For a long period of my life, existentialist authors had “all my thought and love” (to borrow a phrase from Yeats).

I somehow made my way into a adulthood. But God it was hard!