Tuesday

Oops, I just realized that I missed Banned Book Week, thinking that it was this week rather than last. With the alarming rise of book bans nationwide, however, every day is a good day to push back against the forces of illiberalism so here goes.

Esquire’s Charles Pierce has alerted me to Pen America’s survey of banned books. Pierce sums up their findings as follows:

From July 2021 to June 2022, PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans lists 2,532 instances of individual books being banned, affecting 1,648 unique book titles. The 1,648 titles are by 1,261 different authors, 290 illustrators, and 18 translators, impacting the literary, scholarly, and creative work of 1,553 people altogether. Bans occurred in 138 school districts in 32 states. These districts represent 5,049 schools with a combined enrollment of nearly 4 million students.

Pen America breaks down the titles into the following groupings:

–674 titles (41 percent) explicitly address LGBTQ+ themes or have protagonists or prominent secondary characters who are LGBTQ+ (this includes a specific subset of titles for transgender characters or stories—145 titles, or 9 percent);

–659 titles (40 percent) contain protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color;

–338 titles (21 percent) directly address issues of race and racism;

–357 titles (22 percent) contain sexual content of varying kinds, including novels with some level of description of sexual experiences of teenagers, stories about teen pregnancy, sexual assault and abortion as well as informational books about puberty, sex, or relationships;

–161 titles (10 percent) have themes related to rights and activism;

–141 titles (9 percent) are either biography, autobiography, or memoir; and

–64 titles (4 percent) include characters and stories that reflect religious minorities, such as Jewish, Muslim and other faith traditions.

PEN also looks at the forces that are driving the banning:

[A]t least 50 groups [are] involved in pushing for book bans across the country operating at the national, state or local levels. Of those 50 groups, eight have local or regional chapters that, between them, number at least 300 in total; some of these operate predominantly through social media. Most of these groups (including chapters) appear to have formed since 2021 (73 percent, or 262). These parent and community groups have played a role in at least half of the book bans enacted across the country during the 2021–22 school year. At least 20 percent of the book bans enacted in the 2021-22 school year could be directly linked to the actions of these groups, with many more likely influenced by them; in an additional approximately 30 percent of bans, there is some evidence of the groups’ likely influence, including the use of common language or tactics.

Finally, it fingers some of the particular groups that are leading the push:

Of the national groups, Moms for Liberty, formed in 2021, has spread most broadly, with over 200 local chapters identified on their website. Other national groups with branches include US Parents Involved in Education (50 chapters), No Left Turn in Education (25), MassResistance (16), Parents’ Rights in Education (12), Mary in the Library (9), County Citizens Defending Freedom USA (5), and Power2Parent (5)…While some of these groups have existed for years, the overwhelming majority are of recent origin: more than 70 percent (including chapters) were formed since 2021.

Predictably, the groups love to drop the phrases “grooming” and “critical race theory.” As Pierce sees it, their attacks are ultimately attacks on imagination itself because “imagination inevitably leads to curiosity, and curiosity inevitably leads to people asking the question most fundamental to democracy—“What the hell are you people doing?”

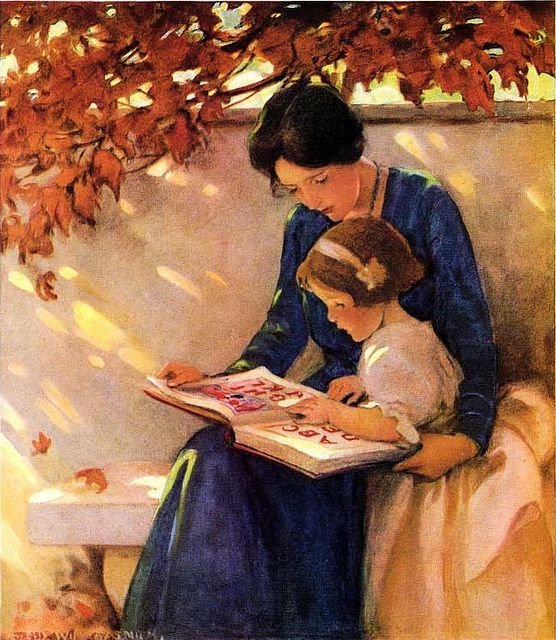

Speaking of imagination, I recommend a short, illustrated Neil Gaiman essay lauding the role of libraries in fostering the imagination. Now we know who to thank for the imagination that brought us such works as the Sandman series, American Gods, Coraline, The Graveyard Book, and The Ocean at the End of the Lane, and others. “Why Our Future Depends on Libraries, Reading, and Daydreaming” appears in the Guardian (you can find it here without a paywall). Here are some of the highlights:

–I suggest that reading fiction, that reading for pleasure, is one of the most important things one can do. I’m making a plea for people to understand what libraries and librarians are, and to preserve both of these things.

–People who cannot understand each other cannot exchange ideas, cannot communicate. The simplest way to make sure that we raise literature children is to teach them to read, and to show them that reading is a pleasurable activity.

— I don’t think there is such a thing as a bad book for children. It’s tosh, it’s snobbery and it’s foolishness. We need our children to get onto the reading ladder: anything that they enjoy reading will move them up, rung by rung, into literacy.

— You’re finding out something as you read that will be vitally important for making your way in the world. And it’s this: The world doesn’t have to be like this! Things can be different.

— Fiction builds empathy. Fiction is something you build up from 26 letters and a handful of punctuation marks, and you, and you alone, using your imagination, create a world and people it and look out through other eyes. You’re being someone else, and when you return to your own world, you’re going to be slightly changed.

— I was lucky. I had an excellent local library growing up, and met the kind of librarians who did not mind a small, unaccompanied boy heading back into the children’s library every morning and working his way through the card catalogue, looking for books with ghosts or magic or rockets in them. Looking for vampires or detectives or witches or wonders.

— They were good librarians. They liked books and they liked the books being read. They had no snobbery about anything I read. They just seemed to like that there was this wide-eyed little boy who loved to read, and they would talk to me about the books I was reading. They would find me other books. They would help. They treated me with respect. I was not used to being treated with respect as an eight-year-old.

— Libraries are about freedom. Freedom to read, freedom of ideas, freedom of communication. They are about education, about entertainment, about making safe spaces and about access to information.

— I do not believe that all books will or should migrate onto screens. As Douglas Adams once pointed out to me, over twenty years before digital books showed up, a physical book is like a shark. Sharks are old. There were sharks in the ocean before the dinosaurs. And the reason there are still sharks around is that sharks are better at being sharks than anything else is.

— Physical books are tough, hard to destroy, bath resistant, solar operated, feel good in your hand. They are good at being books, and there will always be a place for them.

— Books are the way that the dead communicate with us. The way that we learn lessons from those who are no longer with us, the way that humanity has built on itself, progressed, made knowledge incremental rather than something that has to be relearned, over and over.

— We have an obligation to read for pleasure. If others see us reading, we show that reading is a good thing. We have an obligation to support libraries. To protest the closure of libraries. If you do not value libraries, you are silencing the voices of the past and you are damaging the future. As Ray Bradbury said, “Without libraries, we have no future and no past.”

— Fiction is the lie that tells the truth. We all have an obligation to daydream. We have an obligation to imagine. It is easy to pretend that nobody can change anything, that society is huge and the individual is less than nothing. But the truth is individuals make the future, and they do it by imagining that things can be different.

— Albert Einstein was once asked how we could make our children intelligent. “If you want your children to be intelligent,” he said, “read them fairytales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.”

— I hope we can give our children a world in which they will read, and be read to, and imagine and understand.

Do I hear an Amen!