Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951 at gmail dot com and I will send it/them to you. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Spiritual Sunday

Once again, this year’s Lenten discipline will involve taking up a challenging work of literature that I believe will deepen me spiritually. As poet priest Malcolm Guite observes, Lent is a good time for poetry since, through poems, we can arrive at “clarification of who we are, how we pray, how we journey through our lives with God and how he comes to journey with us.” Guite draws on Seamus Heaney and Samuel Taylor Coleridge to make his point:

Lent is a time set aside to re-orient ourselves, to clarify our minds, to slow down, recover from distraction, to focus on the values of God’s Kingdom and on the value he has set on us and on our neighbours. There are a number of distinctive ways in which poetry can help us do that…

Heaney spoke of poetry offering a glimpse and a clarification, here is how an earlier poet Coleridge, put it, when he was writing about what he and Wordsworth were hoping to offer through their poetry, which was

“awakening the mind’s attention to the lethargy of custom, and directing it to the loveliness and the wonders of the world before us; an inexhaustible treasure, but for which, in consequence of the film of familiarity and selfish solicitude, we have eyes, yet see not, ears that hear not, and hearts that neither feel nor understand.”

An article I blogged on twelve years ago, by Marilyn Chandler McEntyre, compares reading literature carefully to the ancient practice of lectio divina, which involves “reading Scripture slowly, listening for the word or phrase that speaks to you, pausing to consider prayerfully the gift being offered in those words for this moment.” Reading this way, she says,

can change the way we listen to the most ordinary conversation. It can become a habit of mind. It can help us locate what is nourishing and helpful in any words that come our way—especially in what poet Matthew Arnold called “the best that has been thought and said”—and it can equip us with a personal repertoire of sentences, phrases, and single words that serve us as touchstones or talismans when we need them.

And:

In each reading of a book or poem or play, we may be addressed in new ways, depending on what we need from it, even if we are not fully aware of those needs. The skill of good reading is not only to notice what we notice, but also to allow ourselves to be addressed. To take it personally. To ask, even as we read secular texts, that the Holy Spirit enable us to receive whatever gift is there for our growth and our use. What we hope for most is that as we make our way through a wilderness of printed, spoken, and electronically transmitted words, we will continue to glean what will help us navigate wisely and kindly—and also wittily—a world in which competing discourses can so easily confuse us in seeking truth and entice us falsely.

Last year I looked for such gifts in Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene, although I only completed Book I and parts of Book III. In previous Lents I turned to the collected poetry of George Herbert, John Milton’s Paradise Regained, the religious poems of T. S. Eliot, and Dante’s Paradiso.

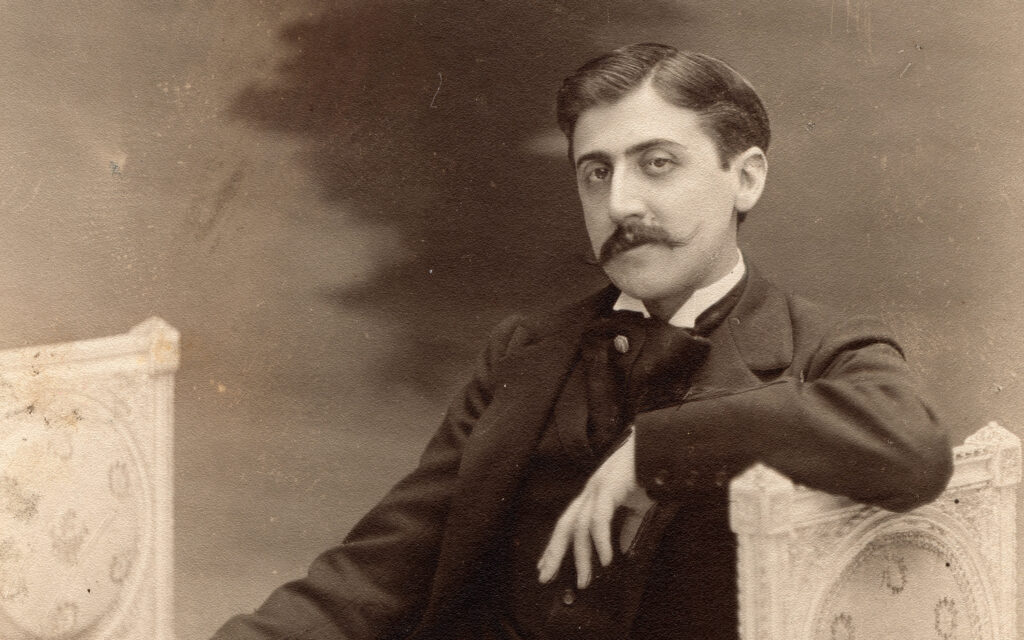

This year I am focusing on Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, a work that has always intimidated me. This is in part because of its length, in part because of the author’s extra-refined sensibility (too subtle for me?), in part because my French professor father lionized it (can I read and appreciate as well as he did?). All of these are reasons to take it on.

Besides, I recently realized, from reading Peter Brooks’s Seduced by Story: The Use and Abuse of Narrative, that Proust has a lot to teach me about the nature of fictional engagement. As the Yale literature professor sees it, Proust understands, in a profound way, why we are drawn to novels. Because our senses can only tell us so much about another person, Proust contends that only through imagining what other people must be feeling and thinking can we overcome our separateness from them:

[N]one of the feelings which the joys or misfortunes of a ‘real’ person awaken in us can be awakened except through a mental picture of those joys or misfortunes; and the ingenuity of the first novelist lay in his understanding that, as the picture was the one essential element in the complicated structure of our emotions, so that simplification of it which consisted in the suppression, pure and simple, of ‘real’ people would be a decided improvement. A ‘real’ person, profoundly as we may sympathize with him, is in a great measure perceptible only through our senses, that is to say, he remains opaque, offers a dead weight which our sensibilities have not the strength to lift.

Although we may see someone else experiencing a misfortune, Proust notes how little our senses can reveal to us the nature of that misfortune. The same is even true when it comes to our own misfortune:

If some misfortune comes to [another person], it is only in one small section of the complete idea we have of him that we are capable of feeling any emotion; indeed it is only in one small section of the complete idea he has of himself that he is capable of feeling any emotion either.

One reason we have difficulty understanding each other, and understanding ourselves, is because the change process occurs so slowly. Speaking of the world’s sorrows and joys, Proust observes that

we should have to spend years of our actual life in getting to know [them], and the keenest, the most intense of which would never have been revealed to us because the slow course of their development stops our perception of them. It is the same in life; the heart changes, and…its alteration, like that of certain natural phenomena, is so gradual that, even if we are able to distinguish, successively, each of its different states, we are still spared the actual sensation of change.

Literature, by contrast, gives us these precious insights. Because it deals with our spiritual selves, it finds a way to penetrate “those opaque sections,” thereby connecting self with other–and self with oneself–as mere empirical observation cannot. Whether through symbol, plot, character, setting, atmosphere, or other literary tools, it finds ways to translate the essence of others in ways that we can grasp. Or as the narrator puts it,

The novelist’s happy discovery was to think of substituting for those opaque sections, impenetrable by the human spirit, their equivalent in immaterial sections, things, that is, which the spirit can assimilate to itself.

In other words, it doesn’t matter that fictional characters are made up. “The feelings of this new order of creatures,” Proust writes, “

appear to us in the guise of truth, since we have made them our own, since it is in ourselves that they are happening, that they are holding in thrall, while we turn over, feverishly, the pages of the book, our quickened breath and staring eyes. And once the novelist has brought us to that state, in which, as in all purely mental states, every emotion is multiplied ten-fold, into which his book comes to disturb us as might a dream, but a dream more lucid, and of a more lasting impression than those which come to us in sleep; why, then, for the space of an hour he sets free within us all the joys and sorrows in the world…

We can learn how the heart changes, Proust says, “only from reading or by imagination.”

I am far enough into the first volume to know that Proust—whose boyhood self is constantly reading—will speak more about the truths that fiction teaches us. I’ll report back regularly on further insights.