Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Friday

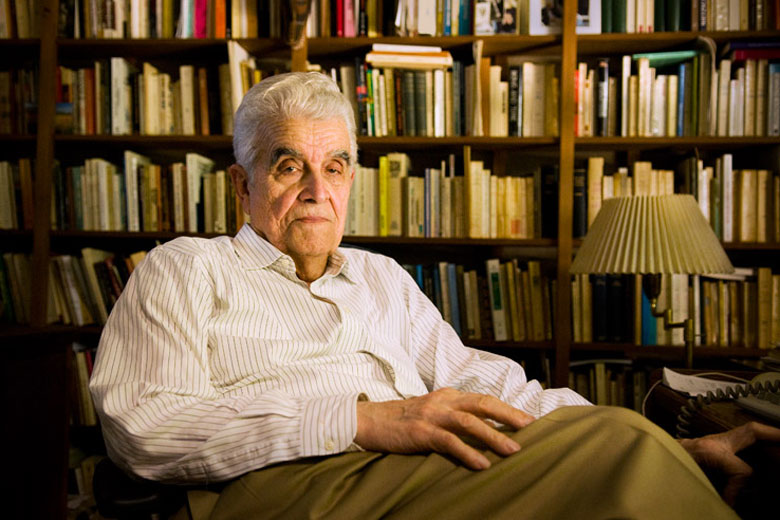

I have been hearing a lot about the philosophical anthropologist René Girard over the past few years. Rebecca Adams, a close friend who edited my forthcoming book, is a Girard scholar who talks about him frequently with me, and Patty, a reader who regularly comments on my blog posts, has forwarded me a Cynthia Haven article on Girard that appeared in the Free Beacon. So he’s due a blog post here.

Girard is most noted for his theory of mimetic (imitative) desire: the desires that make up who we are are determined, not by our own autonomous selves, but by other people. We desire what they desire. Why he warrants a blog post here is because he says he owes his major insights to literature.

In fact, while he writes as a philosopher or anthropologist, Rebecca tells me he sees literature as providing deeper knowledge into the nature of reality than philosophy or anthropology or any other academic discourse. At one point he has written, “Only the great writers succeed in painting these mechanisms faithfully, without falsifying them: we have here a system of relationships that paradoxically, or rather not paradoxically at all, has less variability the greater a writer is.” Among the authors he has turned to are Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Balzac, Flaubert, Dostoevsky, and Proust—and I’m just naming a few of them.

I first became aware of mimetic desire when I was a young parent and was watching my son Justin, then a toddler, play with Ann Finkelstein, the daughter of our best friends in grad school. Although each had a toy, each would become envious of the other’s toy. We used to say that Ann had sprinkled her toy with “magic Annie dust,” which turned it into an object of desire. Of course, Justin was doing his own sprinkling, and I recall only once when the two of them got into perfect sync, exchanging their toys back and forth as each toy acquired its special aura. It was far more common for a squabble to break out.

This squabbling is at the heart of Girard’s anthropology, As Haven explains, our imitative cravings inspire

covetousness and competition as we come to desire what others cannot or will not share. This creates conflict. Even as we insist that we are ineradicably different, we become more alike as we fight—using the same weapons, trading the same insults, inflicting the same injuries against the demonized “other.”

To keep these conflicts from tearing everything apart, societies settle upon a scapegoat, which “brings a sense of resolution and expiation.” Haven mentions as examples the Salem witches and the Chinese intellectuals in Mao’s cultural revolution. And or course there’s the Holocaust.

For literary examples, Haven notes, Girard points to “Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne, Hugo’s Jean Valjean, and Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. (‘Let us be sacrificers, but not butchers,’ Brutus says, before the cabal slaughters their idol.).”

When discussing these ideas with Rebecca, I mentioned Ursula LeGuin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omela,” to which Rebecca replied that it had been the subject of her first article on Girard. In that story, which LeGuin calls a thought experiment, the author asks us to imagine a utopian society in which there is perfect harmony. But because such a society seems fanciful the author must add one essential ingredient: a scapegoat. Once she does, the society becomes more realistic.

The scapegoat in her story is an imprisoned and maltreated child:

[T]he child, who has not always lived in the tool room, and can remember sunlight and its mother’s voice, sometimes speaks. “I will be good, ” it says. “Please let me out. I will be good!” They never answer. The child used to scream for help at night, and cry a good deal, but now it only makes a kind of whining, “eh-haa, eh-haa,” and it speaks less and less often. It is so thin there are no calves to its legs; its belly protrudes; it lives on a half-bowl of corn meal and grease a day. It is naked. Its buttocks and thighs are a mass of festered sores, as it sits in its own excrement continually.

Everyone in Omelas understands that

the happiness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery.

As Girard sees it, scapegoating is at the core of the violence and wars that characterize human history. We shift our internal conflicts to a scapegoat, who then suffers from the attacks we would otherwise direct against each other. I remember the conservative operative, I can’t remember who, who after the Soviet Union fell apart said his party would have to find a new enemy. For a while it was Muslims, then immigrants, and currently it appears to be Democrats.

Haven, writing for a conservative publication, points out that liberals do their own scapegoating, using cancel culture to shame people publicly or shut down discourse. I have also had a conservative reader accuse me of Trump Derangement Syndrome, as though I was turning him into a scapegoat. While I acknowledge that liberals are not immune from the dynamic, in our defense I would argue that Trump’s scapegoating is far more damaging: he built up a devoted fan base by scapegoating first Barack Obama (through his birther conspiracy) and then immigrants. Liberals are less likely than Trump supporters to pick up an automatic rifle and start gunning down members of a scapegoated demographic.

But putting aside which side is worse, it’s certainly true that the dynamic described by Girard has played a major role in human history. It’s a pessimistic way of looking at human beings, who in his view are wired such that violence and scapegoating are inevitable. I therefore find it exciting to talk with Rebecca, who is in the Girard Wikipedia entry for proposing what she calls “loving mimesis.” If we imitate negative desiring, she asks, why can’t we similarly imitate positive desiring? As the Wikipedia entry puts it, “If beneficial imitation is possible, then it is no longer necessary for cultures to be born by means of scapegoating; they could just as well be born through healthy emulation.”

Haven explores a couple of instances of beneficial mimesis. Mimesis is how we learn and how lovers love, she says, in the latter case “trading compliments and promises that escalate and increase their mutual affection.” A literary instance is the balcony scene where Romeo woos Juliet, with “their language escalat[ing] euphorically as they goad each other’s love (to the point of parody, Girard thought).”

I think I would use other literary examples, especially those in which a character experiences a transcendent breakthrough, such as Scrooge or Silas Marner or Jean Valjean or Ivan Ilych. And the great inspiration for all these figures is Jesus, the scapegoat/sacrificial lamb who turned the tables on violence by forgiving those who persecuted him.

Scapegoat violence certainly grabs our attention, but that’s not the only narrative in town.