Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

My father loved Christmas—we had elaborate Dickensian celebrations every year until he died at 90—and Christmas poems such as the one of his I shared yesterday were part of that. Interestingly, my father wasn’t Christian, but he loved the creativity of religious symbolism and the way that different religions freely borrow from each other in their efforts to touch the divine.

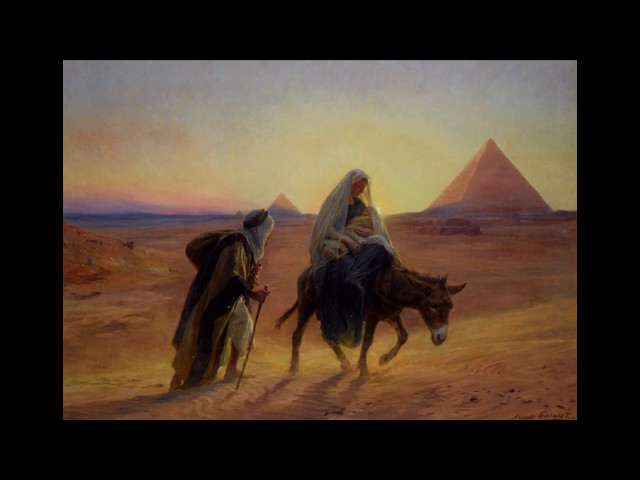

As Scott Bates saw it, the Christmas nativity story was particularly powerful because it has embedded within it narrative elements borrowed from Roman, Greek, Egyptian, and Persian religions (Zoroastrianism). In “Flight into Egypt,” about Joseph, Mary and Jesus fleeing to escape Herod’s slaughter of the innocents, my father imagines the holy family picking up other influences along the way.

Flight into Egypt

By Scott Bates

The falcon’s eye above the pyramid

Moves with the weary travelers far below,

The queen, her consort, and the solar god,

And through the desert on their beast they go

Beneath the sphinx of Gizeh guarding the dead,

Past Isis in her temple nursing her child,

Her silver serpent turning his diamond head

To see them riding westward, into the wild

Land of Mithra and Dionysus, far

from the stable and the kings of Bethlehem,

No dove above them like a guiding star—

But Hathor on the horizon watching them,

Her forehead crowned with stars and double horn,

As they ride towards her on their unicorn.

The falcon’s eye belongs to Horus, the Egyptian god of kingship, healing, protection, the sun, and the sky. He is looking down at the holy family, described as the queen (Mary), her consort (Joseph), and the solar god (Jesus, the son and sun).

The resurrection, Egyptian style, is captured through the sphinx of Gizeh, who looks over the dead, and the mother goddess Isis, who resurrected her slain brother and husband Osiris. The family is also traveling through the lands of Mithra, the Zoroastrian divinity associated with light, the sun, justice and truth, and of Dionysus, a Greek fertility god. And instead of the star of Bethlehem, they are traveling under the watchful eye of Hathor, a sky deity who was mother or consort of Horus and of the sun god Ra.

The ass they ride on, meanwhile, Scott Bates describes as a unicorn because of that beast’s special symbolism for early and medieval Christians. As the Brittanica informs us, the early Christian bestiary Physiologus states that

the unicorn is a strong, fierce animal that can be caught only if a virgin maiden is placed before it. The unicorn leaps into the virgin’s lap, and she suckles it and leads it to the king’s palace. Medieval writers thus likened the unicorn to Christ, who raised up a horn of salvation for mankind and dwelt in the womb of the Virgin Mary.

Bill Pregnall, a former rector, once told me—this when I was wrestling whether to join the church—that there are many roads to the top of the mountain. Christianity is far from the only religion to set important renewal celebrations in the heart of bleak midwinter, when the sun appears to be dying a slow death. These powerful symbols point towards hope in the darkest of times.