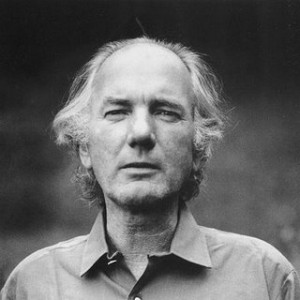

Austrian Novelist Thomas Bernhard

David Lodge’s Small World is the funniest novel I know about international academic conferences. Among the more bizarre scenes is an American Jane Austen scholar, once a New Critic and now a reborn deconstructionist, who against his will is pulled into the bondage and domination games of an Italian feminist poststructuralist.

As described by our University of Ljubljana colleague Jason Blake, his cross-cultural experiences at an international conference devoted to the Austrian author Thomas Bertham were not nearly as exotic. Nevertheless, the difficulties that scholars from different cultures encounter when attempting to communicate are still worth exploring. Enjoy the following piece, which will also teach you a little about Bernhard (1931-1989), considered by many to be Austria’s most important post-war writer and by everyone to be its most provocative.

By Jason Blake, University of Ljubljana English Department

The recent Thomas Bernhard conference in Ljubljana renewed my faith in academic get-togethers. It had no divas complaining about the hotel room or their too-early/too-late/too-something timeslot on the program, and the keynote speakers actually hung around to listen to the rest of us. What the Konferenz did have was a clear focus on a single, irascible writer. A healthy mix of young and old scholars from Europe, the United States, and even Iran delivered good papers all within the standard twenty-minute time limit.

It was also very civil. I mention this because Germans always go for the throat come discussion time, and then go for a chummy beer afterwards. I have yet to solidify my stereotypes about Austrians.

If I ever get around to forming stereotypes about my Alpine neighbors, I won’t base them on anything that the playwright, novelist and general thorn-in-Austria’s-side Thomas Bernhard had to say. Like many German-language writers of his generation, Bernhard wrote about the horrific shadow of the Nazi past, but he did so with a clear focus on the link between past and present. He argued, absurdly I hope, that after World War II Austria merely changed its symbols: down came the swastika, up went the crucifix. He also collected major prize after prize, insulting the prizes and prize-givers as often as he collected them. Other pet topics were the prospect of natural death and its opposite (suicide), along with the redemptive qualities of art, especially music.

It is unlikely, however, that Bernhard ever used the word “redemptive,” even when praising Bach and other great masters of the past. Bernhard’s style and voice are uniquely bitter. In the handful of works I’ve read, he seems to be cork-screwing the German language in on itself through absurdly long yet vibrant neologisms, sentences that flow from here to Vienna, and novels in the form of monologues – always the sign of an opinionated author. Though Bernhard was a huge writer in Austria, and though his plays are regularly staged across Europe, he is no Michel Houellebecq or Günther Grass in terms of North American reception and sales. That said, almost all of his dozen novels, plays and autobiographical writings are available in English. As I learned at the conference, Bernhard is also a presence in Iran.

That the Austrian government sponsored this 80th Birthday Conference in Ljubljana is like George Bush Jr. shelling out for a Philip Roth symposium. “Too horrendous to be forgotten” was one of Roth’s lesser anti-Bush insults in an interview. The novel Exit Ghost also has a few blistering anti-Bushisms.

There is, however, a major difference between Roth and Bernhard’s political views. Whereas the American novelist attacks individual presidents (such as in Our Gang, featuring Trick E. Dixon), Bernhard specializes in poisonous generalizations. His hatred for Austria was the motor that drove much of his writing, and he preferred strong images and blanket slander over nuanced political arguments: Austria is “Europe’s whorehouse,” its government – any government – “a pricey lottery for dummies.” I can’t think of any American author so fond of slinging random darts at his homeland. I can’t think of any Canadian author who throws anything much harsher than padded footballs at Canada.

In Bernhard’s final play, Heldenplatz, a character states that things “are worse for Austrian Jews in 1988 than they were in 1938.” Even if these words are uttered by an actor acting a role on the stage, many critics hear Bernhard’s own voice and convictions behind them. This play premiered in 1988 at Vienna’s Burgtheater, which is as close as you can get to Austrian governmental approval in post-Habsburg times.

Elsewhere, Bernhard compared his compatriots’ mindset to a candy-coated rum-cake (Punschkrapfen): “red on the outside, brown on the inside and always a little drunk.” In other words, though seemingly socialist, Austria is in fact Nazi in the core and confused. How sincere Bernhard was is an open question. If he was merely out to provoke, he was successful.

The late Austrian literary critic Wendelin Schmidt-Dengler admiringly called Bernhard an “Übertreibungskünstler,” an “exaggeration-artist.” The late right-wing populist politician Jörg Haider called Bernhard a “traitor who be stripped of his citizenship,” perhaps alluding to the fact that Bernhard was not actually born in Austria (though he spent his life there). That Bernhard was partly Jewish can’t be forgotten in this context.

Bernhard’s last will and testament was a bizarre piece of performance art: “I want nothing to do with the Austrian state and I take exception not only to any interference but also to any approaching of this Austrian state concerning my person and work in the future.”

One reason why the Conference in Ljubljana was taking place now is that Bernhard said nobody in Austria could touch his work or heritage for twenty years after his death.

My paper was on Bernhard’s portrait of Canadian pianist Glenn Gould in his 1983 novel Der Untergeher (The Loser). The fictionalized Gould is a hodge-podge of half-truths, rumors, complete inventions, lots of Bernhardian traits, and an almost complete disregard for keeping reality in view. Given that Gould died suddenly at age 50 just a few months before the novel was published, and given that friends were still mourning, this was pretty callous behavior on Bernhard’s part.

I opted for an understated delivery coupled with a golly-gee-I’m-just-an-English-teacher demeanor. The paper wasn’t a disaster, but neither did it go as I had assumed. Statements meant to provoke did not, and though there was laughter, it sure didn’t come when I thought it would. Afterwards, a colleague said, “That ain’t the way we do it in German!” So be it. We all have to learn about the way things work in different cultures, even if it’s as something as removed from the real world as conference culture.

And yet, international conferences are the globalized world in miniature because professors travel a great deal, and each has some notion of how person X from country Y is supposed to behave and think.

A professor like Pnin from Nabokov’s eponymous novel would be particularly clueless these days:

Pnin entered a sport shop in Waindrell’s Main Street and asked for a football. The request was unseasonable but he was offered one.

“No, no,” said Pnin, “I do not wish an egg or, for example, a torpedo. I want a simple football ball. Round!”

And with wrists and palms he outlined a portable world. It was the same gesture he used in class when speaking of the “harmonical wholeness” of Pushkin.

The salesman lifted a finger and silently fetched a soccer ball.

Today, fifty years later, it’s unlikely that any visitor could be unaware of American football (though Professor Pnin could probably manage it).

Today, if I went into a shop in England or Germany and asked for a “football,” the salesperson, hearing my North American accent, might back-translate and offer me what he thought I really meant. “No, no,” I would have to say, “I do not wish an egg…” I might have to ask for a soccer ball.

Consider a more serious example: If I, from a culture that understates, exaggerate displeasure to adapt to the more direct German culture, it is only a helpful cultural translation if the other person knows little about my culture’s love of understatement. Otherwise, you have a recipe for unintentional escalation. (Me: “I’d better exaggerate to get my point across…” German: “Man, this Canadian guy must be really annoyed…I’m not going to put up with that…”).

In other words, when two people from different cultures meet, you’ve got stereotypes and expectations bouncing off stereotypes and expectations, modified behavior refracting modified behavior. It can all become very complicated very fast, and after ten years of living in Europe I’m still working on a solution.

Of course, I’ve been dealing here in types and generalizations, leaving out the people-factor. As a friend wrote in a book called KulturSchock Slowenien (an ominously-titled guide to the habits and mindset of Slovenians), “I want people to get to know me as Marco, not just as ‘some German.’”

To return to the Thomas Bernhard conference, my two conference highlights transcended types and generalizations and had to do with the personal.

After the paper given by the Iranian scholar, there were a few requests for clarification on minor points that, I thought, had already been made absolutely clear. This was a matter of personal wavelengths, not generalized cultural background.

During a reading by the German writer Andreas Maier, I and one other individual – from Austria – laughed long and hard at something nobody else in the room found funny. We looked at each other and were suddenly back in grade two trying to stifle the giggles.