Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Tuesday

From time to time I have been posting on Angus Fletcher’s “25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature” (to cite the subtitle of the Ohio State Professor of Story Science’s Wonderworks). Today I look at his account of the revolutionary impact of nursery rhymes, Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, and A.A. Milne. All of these, he says, have unleashed our inner “anarchic rhymer.”

Fletcher starts his chapter by, essentially, castigating John Locke and the Enlightenment for shutting now our imaginative capabilities. Because of Locke’s emphasis on reason, schooling became obsessed with “morality, sober restraint, and industrious prosperity.” Prior to Locke’s new method for educating young minds, set forth in his Essay on Human Understanding, Fletcher writes that young children

had been told creative fictions about “goblins and sprites.” But no more. In the future, they would be drilled only in the “association of ideas” that possessed “a natural correspondence.” Children would, in other words, be taught the laws of physics. From the cradle to the schoolhouse, they would be told that ice was cold and fire hot; that money bought things and dreams did not.”

Before Locke, Fletcher adds, “a child’s education was haphazard and spontaneous, filled with gaps and free time for random imagining.” After Locke, by contrast, a child’s education

became increasingly regimented, formal and serious. Children were placed in rows of desks, where they memorized rules about counting and grammar. They were taught that playtime was for organized games and sports with rules; they were assigned homework to discipline their hours out of school. And so it came to be that in school districts across the globe, idle daydreaming was replaced by practical life skills, logical decisions, and prudent forward planning.

Only in the late 20th century, Fletcher goes on to say, did scientists make “a startling discovery: daydreaming wasn’t a menace, a defect, or a time-wasting indulgence. Daydreaming was good for the mind.”

When not otherwise engaged, Fletcher says, the brain reverts to play, what neuroscientists call “the default mode network.” This mind wandering

has been linked with myriad psychological benefits. It can nurture creativity. It can inspire fresh solutions to nagging old problems. And it can also just be fun, increasing our well-being and making us more cheerful at life.

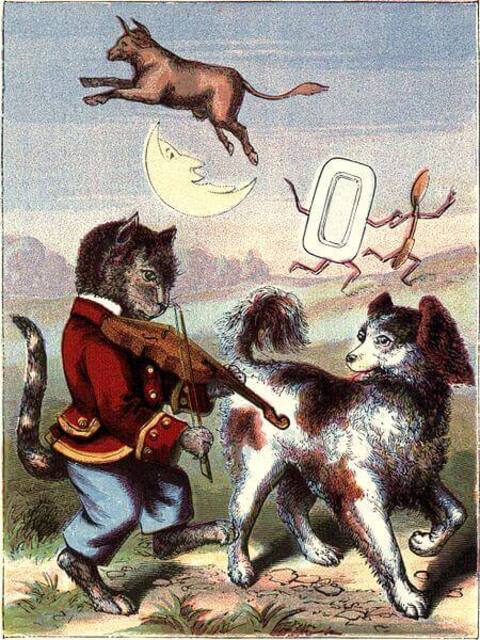

Various works of literature have proven particularly effective at “restoring our natural mind-wandering abilities,” with one of the oldest being the nursery rhyme. Fletcher examines “Hey diddle diddle,” noting that the play between structure (the poem has a syncopated metrical beat and catchy rhymes) and anarchy loosens the stricture of reason and allows us to enter a space where anything is possible. Our brains “frolic audaciously into the unknown.”

Charles Dickens critiques the heirs of Lockean regimentation in Mr. M’choakumchild, the teacher in Hard Times, whom Dickens shows is at odds with the world of the circus. But the works that Fletcher uses to illustrate creative anarchy are the poetry of Lear (he mentions “The Owl and the Pussycat”), Carroll’s Alice books, and Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh books.

Anarchy always requires some sort of structure to set it off. In Alice in Wonderland, the stability of common-sensical Alice is offset by the crazy events going on around her, while in Winnie-the Pooh, it is Pooh who is whimsical in Christopher Robin’s “sensible story-world.” As an example of the latter, Fletcher mentions the episode where Pooh attempts to disguise himself as a cloud as he invades a beehive.

One final author mentioned by Fletcher is Dr. Seuss, who revolutionized children’s books with the Cat in the Hat:

Something went bump!

How that bump made us jump!

We looked!

…And we saw him!

The Cat in the Hat!

Like Pooh, Fletcher writes, the Cat in the Hat “is an anarchist in a storyworld of rules and order.” The admonishing Fish, I would add, functions as a voice of the absent mother. After having indulged in an anarchic scenario, the child reader returns to the world of order as the Cat returns everything to its proper place.

There were moral censors who objected to the Alice books in the 19th century and self-styled guardians who fulminated against Dr. Seuss in the 1950s. That’s one signs that the authors were striking a nerve that needed to be struck.