Spiritual Sunday

I wrote last Sunday about how colleges are not as hostile to religion as rightwing evangelicals charge, and a recent 538 article by Daniel Cox backs this up. Today, I’m going to make an even stronger claim: college can actually strengthen religious faith. If you want your children to have strong and robust religious beliefs, advise them to attend a liberal arts college and to take humanities courses.

Right now, many students associate religion with conservative evangelicals, who come across as shrill and intolerant. They particularly dislike rightwing attempts to control female sexuality. This was clear to me Friday when my Intro to Lit class discussed Lucille Clifton’s menstruation poems, a discussion that veered into religion and the poetry of William Blake.

I’ll elaborate in a moment. First, here’s Cox summarizing some of the attacks on colleges:

In a speech last week at an Alabama university, Donald Trump Jr. alternately mocked and ridiculed the culture of college campuses that teach students to “hate their religion” and “hate their country” — places where the moral teachings of the Bible are held up as “hate speech.” Trump Jr.’s impassioned condemnation of campus politics and college professors has become an increasingly common refrain in conservative politics, particularly among the conservative Christian wing. During the 2012 presidential campaign, Republican Sen. Rick Santorum railed against the indoctrination occurring on college campuses (and used an errant statistic to buttress his claim). A year earlier, Newt Gingrich similarly accused college professors of undermining the Christian values of the Founding Fathers.

The research, Cox observes, does not bear out these claims. The studies he cites confirm what I too have witnessed, especially the third study:

A pair of University of Texas sociologists argue that “the religious belief systems of most students go largely untouched for the duration of their education.” They suggest that, instead, students’ religious lives lie dormant, “waiting to be awakened” upon graduation. Another study found that while education did seem to have a negative impact on religiosity at one point, this is no longer the case. Still other research suggests that religious values neither increase nor decrease so much as they are “reexamined, refined and incorporated” with other beliefs.

Since we push our students to “always question why”—they are at an age where this comes naturally to them—it makes sense that they would be reexamining, refining, and incorporating. They want to know what gives life meaning, and they will occasionally turn their increasing conceptual ability to this question. My church (Episcopalian) likes to say that we don’t check our brains at the door, and I am confident that God can handle any intellectual gauntlets thrown down. Faith only grows stronger when it joins with Reason.

Those who think that Reason is about replacing God have a myopic view of the matter. They see Reason as a sterile tool used to impose human control on the world while banishing mystery, a Dr. Frankenstein-type arrogance, and it is true that such types do exist in the Academy. Many more, however, see reason as a wonderful gift (the religious among us call it a gift from God) for exploring creation in its many manifestations.

In politics we often see a narrow view of Faith battling a narrow view of Reason, with (predictably) narrow conclusions merging. Intellectual inquiry is not politics.

Our class conversation about Lucille Clifton was not narrow. People often love Clifton because she chooses to celebrate subjects that people find shameful, like black skin, large hips, sexuality (especially shameful for abuse victims), and menstruation. In our discussion of “poem in praise of menstruation,” we talked about the origins of the shame that some women still feel about their periods. Students mentioned religions that regard women as “unclean” when they menstruate.

Since my Intro to Lit course has nature as its theme (nature includes biological bodies), we looked at how controlling nature and controlling women’s bodies have often been associated. Pentheus in Euripides’s Bacchae both refuses to worship Dionysus and insists the women remain indoors at their looms. Dionysus, who will not be denied, drives the women into the mountains and upends patriarchal control. In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Morgan Le Fay, essentially a Celtic mother goddess, has the Green Knight humiliate prideful Camelot, proving to Gawain that he is more attached to his body than he admits. In the Green Knight’s eyes, Gawain’s real sin is that he’s ashamed of this attachment.

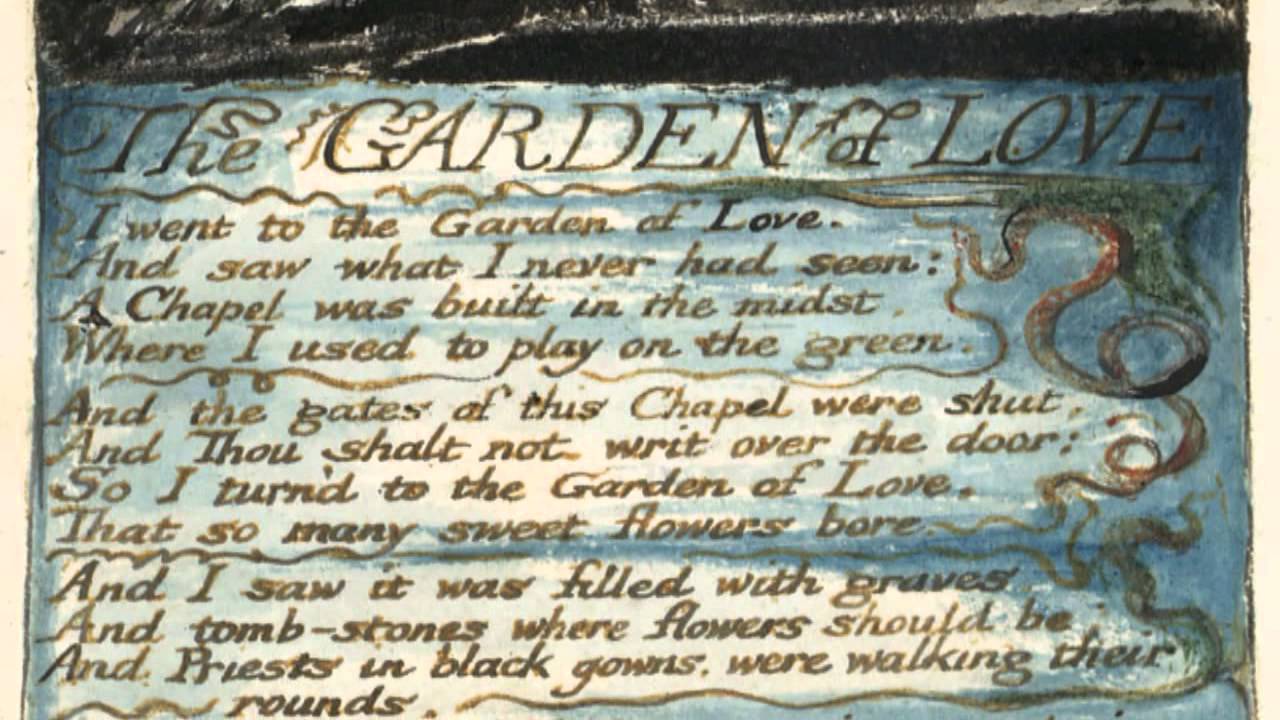

The best poet for our purposes was William Blake, who excoriates the establishment church for the way that it wields shame. In our discussion, we revisited “The Garden of Love”:

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And Thou shalt not. writ over the door;

So I turn’d to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars, my joys & desires.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Habiscus, which my library group discussed two weeks ago, has a horrific example of a church briar binding a child’s desire. The novel features a Christian businessman who is so rigid that he severs ties with his father, a traditional animist, and beats his wife and children whenever he sees them straying. We gain some sympathy, however, once we learn that, when he was a child, a Catholic priest forced him to dip his hands into near boiling water after catching him masturbating. The father relayed that abuse along to his own family.

Presumably even the most doctrinaire of American rightwing evangelicals don’t go to this length. They are not providing my students with positive or effective ways of negotiating the challenges of the modern world, however. Instead, their Christianity appears myopic and reactionary. And it’s not as though my students lack a spiritual hunger. Many turn to our literature, history, art, music, philosophy, and religious studies classes to make sense of life’s spiritual dimensions.

When our students leave us, they take what they have learned and construct their own vision of God and the world. Those who follow a Christian path become deep and soulful Christians.

Rightwing evangelicals don’t trust them to find their own way. It’s as though they have a hothouse image of their faith, believing that it can’t withstand robust questioning. When I recall the many students I’ve had whose parents didn’t allow them to read the Harry Potter books, I think of a conversation in Pride and Prejudice about the difference between “a slight, thin sort of inclination” and “a fine, stout, healthy love.” The first, Elizabeth says, can be destroyed by contact with literature while the second is nourished. Mrs. Bennet begins the conversation:

“When [Jane] was only fifteen, there was a man at my brother Gardiner’s in town so much in love with her that my sister-in-law was sure he would make her an offer before we came away. But, however, he did not. Perhaps he thought her too young. However, he wrote some verses on her, and very pretty they were.”

“And so ended his affection,” said Elizabeth impatiently. “There has been many a one, I fancy, overcome in the same way. I wonder who first discovered the efficacy of poetry in driving away love!”

“I have been used to consider poetry as the food of love,” said Darcy.

“Of a fine, stout, healthy love it may. Everything nourishes what is strong already. But if it be only a slight, thin sort of inclination, I am convinced that one good sonnet will starve it entirely away.”

Are rightwing evangelicals more interested in driving people from Christianity than welcoming them to it? I’m coming to think their faith isn’t very deep. Just angry and loud.