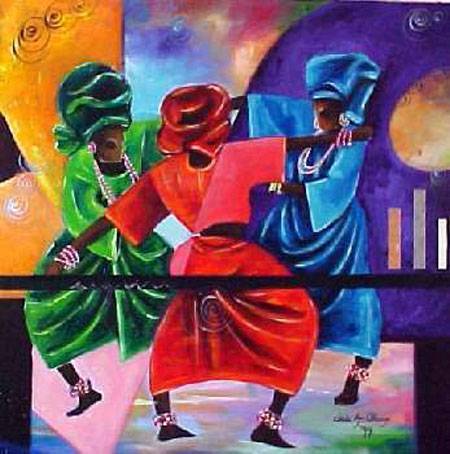

Chidi Okoye (Nigeria)

Chidi Okoye (Nigeria)

Spiritual Sunday

I refute Berkeley thus, Samuel Johnson famously said. And kicked a rock.

Bishop Berkeley was the 18th century idealist philosopher who asked how we know reality is really there if we are dependent upon our senses for perceiving it. Is the rock in existence when we turn our backs?

Johnson’s argument isn’t a philosophical one and it fails to do justice to an interesting line of thought. But it does expose how intellectuals can get so wrapped up in ideas that they lose sight of important things. I think this is Johnson’s point.

I take a Johnsonian approach when I encounter materialist arguments (say, from evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins) about whether there is a spiritual dimension to reality. Only I don’t kick a rock. I point.

I point to Notre Dame cathedral, to Raphael’s Madonnas, to Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, to Shakespeare’s Tempest, to Jane Austen’s Emma, to Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries. Dawkins’ scientific discourse makes grand claims but, in the end, illuminates only a small sliver of existence.

Reader Farida Bag from Uganda sent me the following poem by Gregory Orr, which makes this point in another way. We are more than carcass because we have a divine spark. Furthermore, there is music all around us. When the spark encounters the music, we dance. Dancing is another way of kicking the rock.

To be alive

To be alive: not just the carcass

But the spark.

That’s crudely put, but…

If we’re not supposed to dance,

Why all this music?

After Farida sent me the poem, Uganda was rocked by terrorist explosions that killed 74 people. Farida tells me that one of the incidents occurred only 15 minutes from where she lives (she was asleep at the time). Such heart-wrenching tragedy adds another message to Orr’s poem: we must not let the bombs drown out the music. We must not stop dancing.

Lucille Clifton, who Farida loves, writes about how, in spite of abuse at the hands of her father (he is the man mentioned in the poem below), she kept on dancing. (I discuss Lucille’s resilience in the face of tragedy here.) The moon may have watched and done nothing, as Lucille accuses in her “shapeshifter poems,” but ultimately it provided her enough light to dance by. Here is a poem of hope for all grief-stricken dancers:

only after the death

of the man who killed the bear,

after the death of the coalminer’s son,

did i remember that the moon

also rises, coming heavy or thin

over the living fields, over

the cities of the dead;

only then did i remember how she

catches the sun and keeps most of him

for the evening that surely will come;

and it comes.

only then did i know that to live

in the world all that i needed was

some small light and know that indeed

i would rise again and rise again to dance.