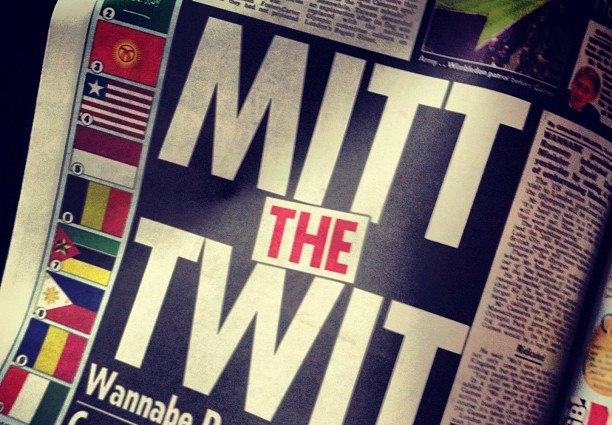

Although I am frequently irritated by Maurine Dowd of The New York Times, I have to admit that she uses literature more effectively than any other political columnist, including David Brooks. Yesterday she cleverly applied Somerset Maugham’s “Appointment in Samarra,” which serves as the epigraph to John O’Hara’s novel by that name, to Mitt Romney’s travails in Britain.

As I’m sure you’ve heard, Romney managed to insult his British hosts in a number of ways, including how they were running the Olympics. Why, Dowd wonders, does Romney make so many inept statements given his obsession with tight scripting? This obsession apparently goes back to a moment when his father, campaigning for president, visited Vietnam and complained that he had been brainwashed by American generals in a visit to Vietnam. The verbal misstep may have cost Romney the presidency. As Dowd notes, younger Romney has been determined that the same won’t happen to him:

In their book The Real Romney, Michael Kranish and Scott Helman quoted Mitt’s sister Jane as saying the episode deeply affected Mitt: “He’s not going to put himself out on a limb. He’s more cautious, more scripted.”

That’s when Mitt began to build his own sterile biosphere, shaping his temperament and political career to make sure he never stumbled into such a costly moment of candor.

Even though the Mormon doesn’t drink coffee, he has measured out his life in coffee spoons, limiting access to reporters, giving interviews mostly to Fox News, hiding personal data, resisting putting out concrete policy proposals, refusing to release tax returns, trimming his conscience to match the moment, avoiding spontaneity. But somehow he ended up making the same unforced error that his dad did.

And now here’s Maugham’s story. It is narrated by Death:

There was a merchant in Bagdad who sent his servant to market to buy provisions and in a little while the servant came back, white and trembling, and said, Master, just now when I was in the marketplace I was jostled by a woman in the crowd and when I turned I saw it was Death that jostled me. She looked at me and made a threatening gesture. Now, lend me your horse, and I will ride away from this city and avoid my fate. I will go to Samarra and there Death will not find me. The merchant lent him his horse, and the servant mounted it, and he dug his spurs in its flanks and as fast as the horse could gallop he went. Then the merchant went down to the marketplace and he saw me standing in the crowd and he came to me and said, Why did you make a threatening gesture to my servant when you saw him this morning? That was not a threatening gesture, I said, it was only a start of surprise. I was astonished to see him in Bagdad, for I had an appointment with him tonight in Samarra.

As Dowd applies the lesson, “You can run from fate, but fate will be waiting in the next town, at the next marketplace.”

I would actually turn Dowd’s observation up a notch. It’s not only fate at work. Rather, what you will encounter is precisely that which you are are trying to escape.

I therefore suggest another work for Dowd, which is Chinua Achebe’s great novel Things Fall Apart. In the Nigerian masterpiece, a son with a good-for-nothing father determines that he will be everything that his father is not. Where his father is lazy and easygoing, he is harsh and driven, and where his father has large debts, he builds up great wealth. Yet almost inexorably, in spite of himself, he disgraces himself at a banquet, is rejected by his son just as he rejected his father, and ultimately is buried in the same cemetery of outcasts where his father lies. By defining himself so entirely against his father, he never escapes him but instead shares his fate.

Perhaps we should modify George Santayana’s famous statement and say that those who learn too much from history are bound to repeat it. Instead of trying to be the self that he thinks the public wants, maybe Romney should just show the world who he is, rich guy warts and all. Since those warts will all be revealed anyway, he might as well get credit for candor.

Further thoughts: Further kudos to Dowd for the allusion to T. S. Eliot’s “Prufrock” (“I have measured out my life with coffee spoons”), which means that, for her, Romney is

not Prince Hamlet nor was meant to be;

[Is] an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous–

Almost, at times, the Fool.

Later in the article she impressively borrows from Merchant of Venice and calls Romney a “want wit.” But all that being said, I have doubts about Dowd’s focus on personality-driven politics. In the end, I believe, Romney’s fate does not hinge upon gaffes. He will win if the economy gets much worse and he will lose if enough people grasp the impact of his proposals to lower taxes on the wealthy and deregulate the financial sector.