Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at [email protected]. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Sunday

My friend Rebecca Adams alerted me to a Diane Butler Bass essay about celestial fire that shares two powerful fire poems. Bass observes that, with the California fires raging, it can be unsettling to encounter John the Baptist’s prediction for Jesus: “He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire.” As Bass observes, fire “is a horror of torture and destruction, apocalypse and hell. We know the spiritual implications. We’ve seen the pictures. Perhaps we’ve even experienced the threat or the flames.”

But then she notes that fire

is something else as well — it burns off the chaff of delusion, falsity, and self-hatred. With this fiery baptism three things are revealed: the true self, the central meaning of existence, and a holy welcome. Identity, love, and acceptance.

In her essay, Bass notes that our first impulse, when confronted with fire, is to run towards it. She notes that “every person I knew in New York City on 9/11 ran toward the Twin Towers to help.” The same has been true with the California fires:

There was a man who attempted to save his entire block with a garden hose. Neighbors who rescued pets. A few people who watered down their houses in order to protect not only their property but an entire neighborhood behind their homes. A friend of mine whose house in Malibu burned mourned not for her loss but for the losses of her neighbors. And still others I know, evacuated from their own homes, occupied themselves by feeding, serving, and comforting other evacuees. Yes, they fled. But not before helping — and not before thinking about and trying to do something for their relatives, friends, neighbors, and even strangers.

“Fire is like that,” she writes. “Before running away, we often run toward.” Her two poems are both about running towards.

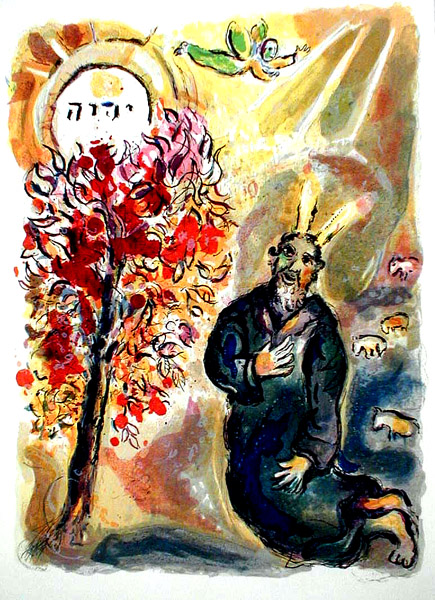

First, there’s David Whyte’s “Fire in the Earth,” about Moses walking towards the burning bush. Whyte compares it to losing one’s house in a fire, which far too many people can relate to these days, whether in California or Gaza. What seems like the end, however, Whyte describes as a beginning. Your old life must burn away if you are to embrace your life’s mission:

Like the moment you too saw, for the first time,

your own house turned to ashes.

Everything consumed so the road could open again.

At such moments, one becomes a living flame:

Your entire presence in your eyes

and the world turning slowly

into a single branch of flame.

Here’s the poem:

Fire in the Earth

By David Whyte

And we know, when Moses was told,

in the way he was told,

“Take off your shoes!” He grew pale from that simplereminder of fire in the dusty earth.

He never recovered

his complicated way of loving againand was free to love in the same way

he felt the fire licking at his heels loved him.

As if the lion earth could roarand take him in one movement.

Every step he took

from there was carefully placed.Everything he said mattered as if he knew

the constant witness of the ground

and remembered his own face in the dustthe moment before revelation.

Since then thousands have felt

the same immobile tongue with which he tried to speak.Like the moment you too saw, for the first time,

your own house turned to ashes.

Everything consumed so the road could open again.Your entire presence in your eyes

and the world turning slowly

into a single branch of flame.

The other poem, by Mary Oliver, has to do with erotic passion. When one falls in love, does one play it safe or walk directly into the danger?

The speaker sounds as though she has been emotionally bereft, a cold city and a motionless heart. Perhaps a loveless childhood has made opening herself up to her feelings feel like a cataclysm, which means that she must go back if she is to go forward. Internally aflame, she must run into the fire to find the door:

The Fire

By Mary Oliver

That winter it seemed the city

was always burning – night after night

the flames leaped, the ladders pitched forward.

Scorched but alive, the homeless wailed

as they ran for the cold streets.

That winter my mind had turned around,

shedding, like leaves, its bolts of information –

drilling down, through history,

toward my motionless heart.

Those days I was willing, but frightened.

What I mean is, I wanted to live my life

but I didn’t want to do what I had to do

to go on, which was: to go back.

All winter the fires kept burning,

the smoke swirled, the flames grew hotter.

I began to curse, to stumble and choke.

Everything, solemnly, drove me toward it –

the crying out, that’s so hard to do.

Then over my head the red timbers floated,

my feet were slippers of fire, my voice

crashed at the truth, my fists

smashed at the flames to find the door –

wicked and sad, mortal and bearable,

it fell open forever as I burned.

Of course, in the case of actual fires, run in the opposite direction. Metaphorical fires are a different matter.