Film Friday

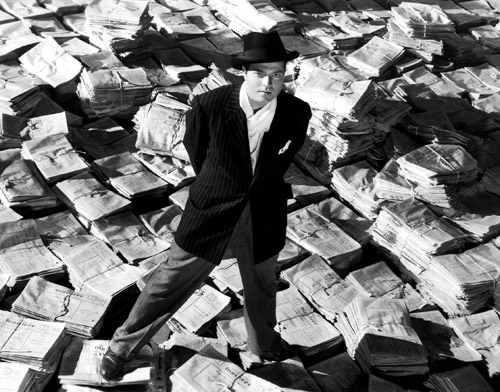

Since the Rupert Murdoch scandal broke, a number of commentators have compared the media magnate to Charles Foster Kane of Orson Welles’s 1941 classic. I pursue that parallel here for what it can teach us about one of Murdoch’s most galling claims: that he is anti-elitist.

Let’s first review what we know so far. Murdoch ran into trouble when it was discovered that the tabloid News of the World hacked into the voicemail box of a girl who had been kidnapped and murdered. Then the rest of the dirty linen started revealing itself. Now it appears that the hacking also involved families of dead servicemen, the royal family, Prime Minister Gordon Brown (through hacking, News learned that his son had been born with cystic fibrosis), and maybe even (although this is as yet unconfirmed) the families of 9-11 victims.

And then there are the policemen bribed, the politicians pressured, the reporters (especially those working for Murdoch papers) intimidated.

To contain the damage, Murdoch has closed down News of the World and fired all of its staff (many of them innocent). There have been resignations, including the editor of Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal and the top two officials of Scotland Yard. There have been arrests, including British Prime Minister David Cameron’s former director of communications Andy Coulson and Murdoch confidant Rebekah Brooks. Murdoch has withdrawn his attempt to take over British Sky Broadcasting, and Cameron is frantically trying to disassociate himself from Murdoch. The story looks far from over.

Meanwhile, Murdoch’s rightwing outlets in America (The Wall Street Journal, Fox News, The New York Post) are doing fancy footwork in response. WSG, after all but avoiding the story, ran an article complaining about critics of Murdoch indulging in Schadenfreude. One approach that isn’t working at present is blaming the liberal media.

Interestingly enough, a number of liberal columnists have had good things to say about Murdoch over the years. Newspapers are in such trouble that figures such as Eugene Robinson and David Ignatius of The Washington Post and Roger Cohen and Joe Nocera of The New York Times were relieved that someone with money was taking an interest. While they didn’t agree with Murdoch’s politics or tactics, they liked how he was breathing life into newspapers. Nocera now apologizes for his support, noting that, rather than saving WSG, Murdoch turned it from a great newspaper into a mediocre one.

Charles Foster Kane is also the toast of liberals early in his career. Kane is unlike the born-wealthy Murdoch (or for that matter William Randolph Hearst, on whom he is based) in that he comes from “humble beginnings.” But both Kane and Murdoch carry a permanent grievance against elites. When Thatcher, the banker (based on J.P. Morgan) who raises young Kane and who buys him out when Kane goes bankrupt, asks him what he wished he could have become, Kane replies, “Everything you hate.” The Australian-born Murdoch, meanwhile, sees himself as a populist. Here’s Jack Schaefer of Slate:

Murdoch despises all establishments and practically all institutions—the BBC, Parliament, the “royal” family, the New York Times, patricians, and practically anybody who doesn’t conform to his populist self-image.

Ignatius, meanwhile, says that Murdoch carries a permanent “defy the establishment” chip on his shoulder that communicates itself to his publications:.

This sense of victimization goes deep in News Corp. Executives have often responded to criticism with aggrieved indignation — arguing that opponents are elitist and out of touch with the masses. In a November 2010 speech to a conference of British editors, [Managing Director of News of the World Bill] Akass defended his brand of tabloid journalism against the “snobbish elite,” saying that their complaints were “a kind of proxy for sneering at the working class.”

Such attitudes help explain the connection between Fox News and Tea Party rage.

Back to Kane. He is as irreverent towards established authority as Murdoch and scandalizes Thatcher when, as a young man, he decides that “it would be fun to run a newspaper.” In a slapstick scene, he takes over the very staid and boring New York Inquirer and decides that he will make it as essential to the public as the gas in the office’s gas lamp. His first story is a concocted one about a missing person. In a line that prefigures Murdoch’s New York Post, famous for its eye-catching headlines, he says that what makes a story is not the content but the size of its headline.

We see the two kinds of journalism contrasted in the film. While Kane is three-dimensional and full of life, the news organization that sends its reporter to track down the secret of rosebud is always in shadow. Welles makes this visual choice to contrast Kane with Time/Life’s Henry Luce, who was cultivating a blander and less personality driven news style than Hearst’s yellow journalism. For decades, articles in Time did not have bylines, as though they were just anonymous truth.

Early in his newspaper career, Kane sets himself up as a defender of “the working man.” He goes after slumlords and, when he decides to run for office, does so as a progressive populist. But there are early signs he does not care as much about “the workingman” as he claims.

For instance, when he is laying out his “declaration of principles” for the Inquirer’s first issue under his editorship, he repeatedly uses the word “I.” He claims that this is to hold himself accountable, but it becomes clear that it is rather a case of self-aggrandizement. In fact, when he starts running for political office, his populist campaigns are more to satisfy his anger against Thatcher than to better the plight of average Americans.

As his giant campaign poster of himself proclaims, Kane has loyalty to only one man: himself. Kane is like Murdoch in that he has the money to buy whatever he wants, and he uses those around him as instruments. In one regard, Murdoch may be even more heartless than Kane: he appears willing to cast off country, friends, and even family as it suits his purposes.

When Kane, as a result of his tryst with Susan Alexander, loses his race for New York governor, he complains to Leland, “All right, that’s the way they want it, the people have made their choice. It’s obvious the people prefer Jim Gettys to me.” To which Leland, in a response that could be applied to Murdoch’s so-called concern for his tabloid audiences, replies, “You talk about the people as though you owned them, as though they belong to you.”

Murdoch, like Kane, may seem hard to categorize politically—Kane is called everything from communist to fascist and Murdoch, while obviously rightwing, has nevertheless supported Hillary Clinton and Tony Blair—but both men can be understood when their true allegiances are revealed. They will do anything to keep themselves uppermost. Unfortunately, unlike Kane, Murdoch is far from ruined. He may have suffered reversals, but he still has the ability to inflict a lot of damage to civic discourse.

Murdoch isn’t anti-elitist. He just resents anyone that is more powerful than he is. To turn to the film again, when Kane’s wife chastises him for criticizing the president–“He happens to be the president, Charles, not you”– Kane asserts, “That’s a mistake that will be corrected one of these days.”

At the heart of Welles’ film is a vision of lost innocence. There once was a time, it posits, when America played in the snow and all things seemed possible. Murdoch’s publications, claiming to speak for such Tea Party longings, promise to lead America back of some version of Kane’s boyhood home in New Salem, Colorado. But Murdoch has a very different agenda than Tea Party patriots, and those who follow his lead are being played for suckers.

Added note

The following passage from a column by The Washington Post‘s Richard Cohen (who makes the Kane comparison) reminds me of one of the most famous lines from Citizen Kane. Cohen first:

In the United States, Murdoch is feared mostly for the New York Post, which loses an estimated $60 million a year. This is chump change to Murdoch (net worth: $7.6 billion) but a bargain at twice the price for the political influence it gives him. The paper mugs its enemies for the sheer fun of it all — over and over again. This repetition gives it a sort of torque that no politician can ignore.

In the film, Thatcher, outraged by how Kane is attacking him, asks him if he’s aware that his newspaper lost $1 million the previous year, to which Kane smugly replies,

You’re right, I did lose a million dollars last year. I expect to lose a million dollars this year. I expect to lose a million dollars next year. You know, Mr. Thatcher, at the rate of a million dollars a year, I’ll have to close this place [dramatic pause] in 60 years.

Incidentally, another film has just entered the discussion. According to Forbes, the executive head of a Murdoch-owned marketing firm that is notorious for its heavy-handed tactics against competitors has used the Brian de Palma movie The Untouchables to rally his sales force. If you know the film, can you guess which scene gets mentioned? Here’s the account:

Paul V. Carlucci takes no prisoners. The head of a marketing division of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., Carlucci once rallied his sales force by showing a film clip from The Untouchables in which Al Capone beats a man to death with a baseball bat.

Go here to subscribe to the weekly newsletter summarizing the week’s posts. Your e-mail address will be kept confidential.

One Trackback

[…] I wrote on Murdoch and Citizen Kane last Friday, I didn’t mention how the film itself commits a very Murdochian violation. As I discuss in […]