Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

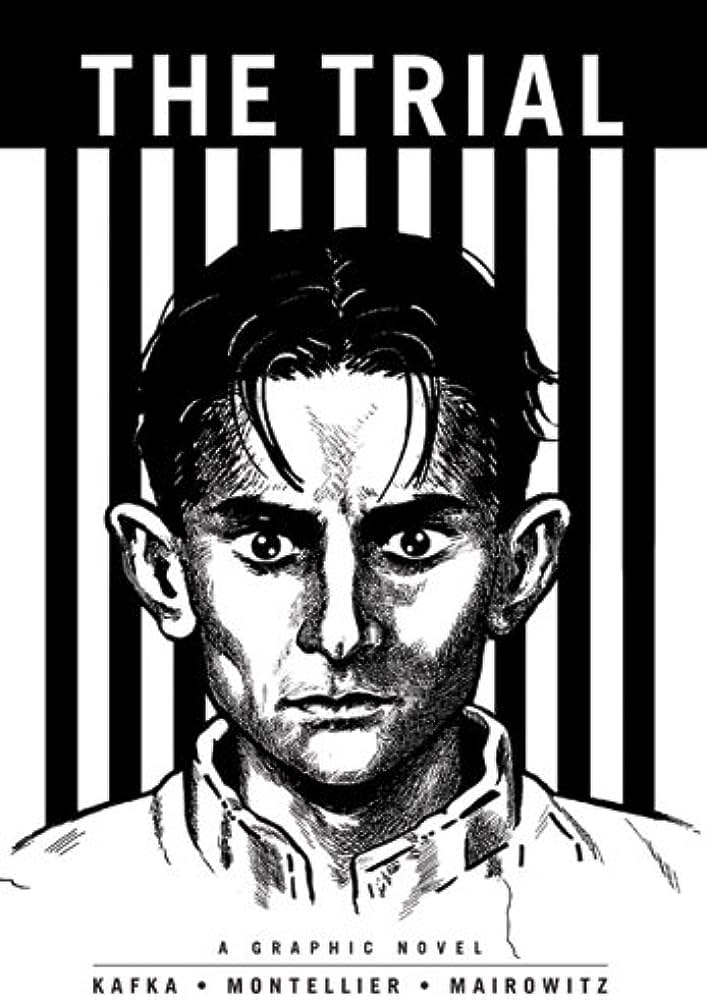

There are different ways to interpret Franz Kafka’s nightmarish visions. Some read his stories as vivid allegories of being trapped in one’s mind, where guilt, paranoia, and a pervading sense of dread combine to plunge us into depression. Others, such as imprisoned Russian dissident Valdimir Kara-Murz, see them as an objective description of life under authoritarian rule.

Kara-Murz, who has been in jail since April for speaking out against the Ukraine invasion, alludes to Kafka in a recent Washington Post column. In it he describes his experience of serving as a defense witness for Alexei Navalny, the opposition candidate that Putin first imprisoned, then poisoned, and then imprisoned again. Kara-Murz participated in the hearing through a video link while locked inside an iron cage. He describes the scene:

What I saw made me think of a scene in Franz Kafka’s The Trial in which the protagonist, facing a prosecutor and assembled guests in the attic of a random residential building, has to respond to charges of which he has no knowledge. The room on the video screen looked like a school gym. At the head of the court, under a double-headed eagle clumsily fastened to the wall, sat Moscow City Court Judge Andrei Suvorov, with his chair behind a small (also school-type) desk. His judicial gown looked strikingly out of place given the circumstances. The room was filled with men in black masks and khaki uniforms. At another table by the wall on the left side of the screen sat the defendant surrounded by his lawyers — and it was only when he stood up to approach the camera and speak that I realized it was Alexei Navalny.

Here’s the episode from The Trial that Kara-Murz references:

K. thought he had stepped into a meeting. A medium sized, two windowed room was filled with the most diverse crowd of people—nobody paid any attention to the person who had just entered. Close under its ceiling it was surrounded by a gallery which was also fully occupied and where the people could only stand bent down with their heads and their backs touching the ceiling….

At the other end of the hall where K. had been led there was a little table set at an angle on a very low podium which was as overcrowded as everywhere else, and behind the table, near the edge of the podium, sat a small, fat, wheezing man who was talking with someone behind him.

It was not only the setting that reminded Kara-Murz of The Trial. Because Navalny could only ask for Kara-Murz’s supportive testimony in terms of his official indictment, his questions proved to be “no less Kafkaesque than the surroundings.” Presumably, Kara-Murz answered “no” to the following queries, but there’s a sense of unreality in Navalny having to ask them at all:

Does public opposition to the government constitute extremist activity? Is the freedom of public demonstrations conditional on permission by the authorities? Was [Navalny’s] 2013 campaign for mayor of Moscow (where he came in second with 27 percent of the vote) just a cover for his underground illegal activities? Were Alexei’s anticorruption investigations detailing the riches of Vladimir Putin and his close entourage slanderous fabrications? And so on. A few times I had to ask whether the question was serious. “Unfortunately, yes — that is my indictment,” Alexei would respond each time.

The questions are Kafkaesque because, as becomes quickly clear while reading The Trial, dialogue seldom has a natural feel to it. It’s as though everything has been run through a bureaucratic filter. Even a conversation that K has with his uncle is skewed and elliptical.

Kara-Murz would undoubtedly characterize Navalny’s and his own trials as Kafkaesque, given that the outcomes are predetermined. That’s also the case with K, as he is informed by a court painter with insights into how the system works:

We’re talking about two different things here, there’s what it says in the law and there’s what I know from my own experience, you shouldn’t get the two confused. I’ve never seen it in writing, but the law does, of course, say on the one hand that the innocent will be set free, but on the other hand it doesn’t say that the judges can be influenced. But in my experience it’s the other way round. I don’t know of any absolute acquittals but I do know of many times when a judge has been influenced. It’s possible, of course, that there was no innocence in any of the cases I know about. But is that likely? Not a single innocent defendant in so many cases? … I hardly ever got the chance to go to court myself but always made use of it when I could, I’ve listened to countless trials at important stages in their development, I’ve followed them closely as far as they could be followed, and I have to say that I’ve never seen a single acquittal.

Russia is notorious for its high conviction rates, especially when it comes to those who oppose Putin. So yes, “Kafkaesque” is an apt description.