One of my students, while serving an internship in Maryland’s state capitol, discovered in my British Literature survey that Milton has something important to say about politicians. Satan, Michael Adams argued in his essay for the course, is a perfect example of someone who spouts populist rhetoric but is really only out for himself.

Recipient of a scholarship set up by former Maryland governor Donald Schaefer, Michael was in Annapolis a lot this past semester. It therefore made sense for him to examine Satan’s leadership style.

Many students admire Satan, of course. But they admire him for the same reasons that people admire demagogues: he is bold and charismatic and he speaks a language that mixes liberation and grievance. Think of him as a Mussolini, a Mao or a Castro.

Or a Cromwell. Milton admired Cromwell as long as he was espousing republican ideals. When, however, he began assuming dictatorial powers, the poet became disillusioned. The poem, written after Cromwell had died and Charles II had been restored to the throne, tries to figure out what went wrong.

Michael noted that Satan is very good at speaking about liberty and freedom:

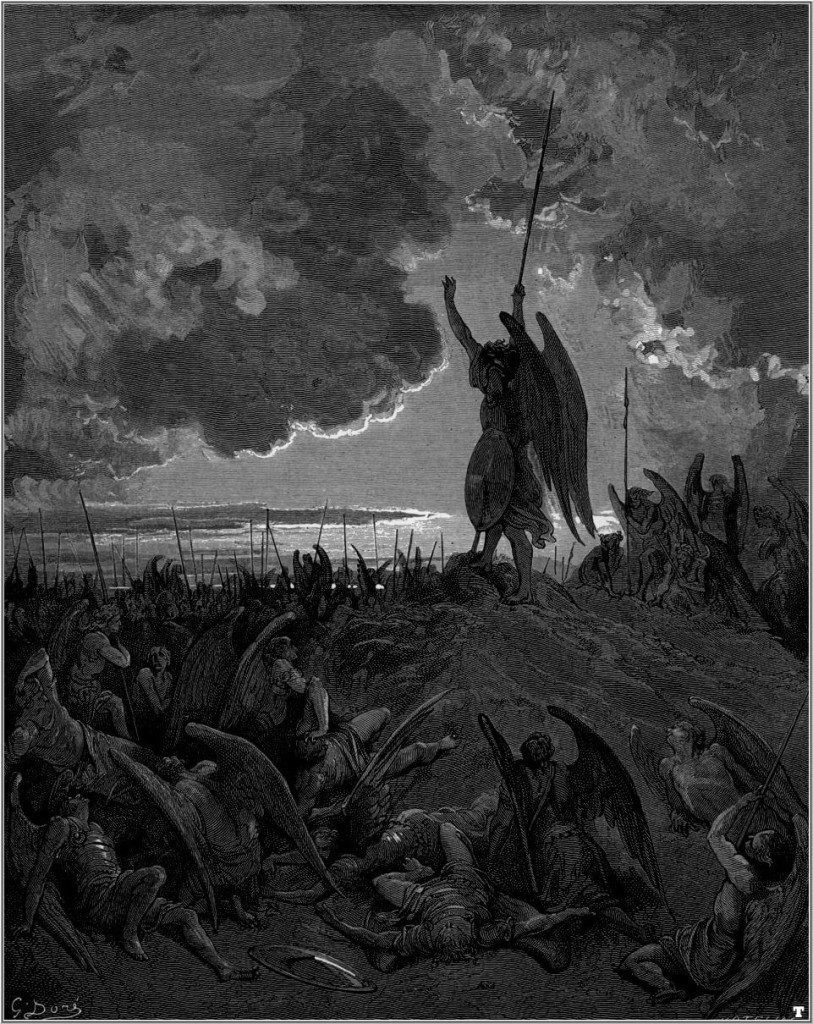

Characterized by lofty, grandiose rhetoric and frequent use of rhetorical questions, the speech is clearly reminiscent of political rhetoric. Milton’s visually rich poetry makes it easy to imagine Satan at a lectern before his followers, gesturing wildly and delivering this rousing speech.

All is not lost; the unconquerable Will,

And study of revenge, immortal hate,

And courage never to submit or yield:

And what is else not to be overcome?

That Glory never shall his wrath or might

Extort from me. To bow and sue for grace

With suppliant knee, and deify his power,

Who from the terror of this Arm so late

Doubted his Empire, that were low indeed,

That were an ignominy and shame beneath

This downfall; since by Fate the strength of Gods

And this Empyreal substance cannot fail,

Since through experience of this great event

In Arms not worse, in foresight much advanc’t,

We may with more successful hope resolve

To wage by force or guile eternal

War Irreconcilable, to our grand Foe,

Who now triumphs, and in th’ excess of joy

Sole reigning holds the Tyranny of Heaven.

Michael noted how the speech is indeed impressive:

Here, like any political leader must after a heavy loss, Satan is rallying his troops and insisting that the fight is not yet over. “All is not lost,” Satan tells his followers, insisting that he has not lost his will, his desire for revenge, his hatred, or his courage. “And what is else not to be overcome?” he asks, as in, “If we still have this, then God has not won at all.” The real shame, Satan insists, would be “to bow and sue for grace with suppliant knee.” This loss is less shameful than that would be, and Satan and his followers can wage “eternal war” against one who now sits above “in th’ excess of joy” and exerting “the Tyranny of Heaven.”

Of course, God-as-tyrant is Satan’s spin. Satan reveals his true colors when he sets himself up as a monarch:

Till at last

Satan, whom now transcendent glory rais’d

Above his fellows, with Monarchal pride:

Conscious of highest worth, unmov’d thus spake…

About which Michael wrote,

While in Book I Satan is portrayed as an authentic leader, now his power comes from a throne and “transcendent glory,” which sets him above his former equals. He exhibits “Monarchal pride,” perhaps the most damaging of all possible descriptors for a political leader in Milton’s eyes, since it implies that Satan now believes himself to be divinely sovereign, imposing himself on what is reserved for God alone. Satan is then referred to as “The Monarch” throughout the rest of the work, for instance when he calls a war council.

Michael demonstrated how Satan carefully engineers this supposedly open meeting of war lords:

After various figures have stood and offered their opinions, Satan goes last and offers his plan of taking heaven through the corruption of Man. Milton writes,

Thus saying rose

The Monarch, and prevented all reply,

Prudent, lest from his resolution rais’d

Others among the chief might offer now

(Certain to be refus’d) what erst they fear’d;

And so refus’d might in opinion stand

His Rivals, winning cheap the high repute

Which he through hazard huge must earn. But they

Dreaded not more th’ adventure then his voice

Forbidding; and at once with him they rose…

While Satan initially presents himself as an advocate for fairer, more republican discourse, now he rules like a tyrant, forbidding any response or criticism after he has spoken. Not only does he disallow feedback, but also his potential rivals hold back, unwilling to offer any because they “dreaded his voice forbidding.” With his rise to the kingship of Hell, Satan…now mirrors the very “tyranny of Heav’n” that he wishes to overthrow.

Lest we have doubts, Michael pointed out that Satan all but confesses his true aims in his moment of doubt in Book IV:

The disparity between Satan’s private misgivings and his radical public certainty is typical of disingenuous politicians who use inflated rhetoric and charisma to manipulate others to their own advantage. Satan, in a moment of honesty, acknowledges that his cause is not motivated by genuine ideals but only by blind ambition, hubris, and thirst for more power.

After showing how politicians can go bad, Michael then set forth what Milton says they should do instead. Michael, incidentally, is Jewish, so when he talks about following the Holy Spirit and espousing “Christian faith,” he is using Milton’s framework. To articulate the idea in non-religious language, one might say that a politician’s primary allegiance is to the public and that he or she must function, above all, as a servant of the people. Here’s Michael:

Paradise Lost can therefore be understood as Milton’s educational guide to the dangers [faced by] political leaders when put in positions of power. In the final Book XII, the Archangel tells Adam how God will send a holy intercessor to protect mankind, saying,

But from Heav’n

He to his own a Comforter [the Holy Spirit] will send,

The promise of the Father, who shall dwell

His Spirit within them, and the Law of Faith

Working through love, upon their hearts shall write,

To guide them in all truth, and also armed

With spiritual Armor, able to resist

Satan’s assaults…

Michael concluded,

Through the perspective of Paradise Lost as a teaching tool, this quote is the ultimate takeaway that Milton wishes students to receive from the lesson. “Law of Faith” and “working through love” is what will “guide them in all truth.” In other words, adherence to Christian doctrine and striving to be Christ-like is what a true political system and political leader should strive for. “Spiritual Armor” is the only protection from “Satan’s assaults.” If Satan is symbolic of political leaders who use their abilities for manipulation rather than public service, then “Spiritual Armor” is symbolic of what Milton believed government was missing: true adherence to Christian faith…

Are you as excited as I am that such a student is planning a life of public service? I like to think that when Satan beckons—as he invariably will whenever power and money are involved—Michael will think back on Milton and will do the right thing.