Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

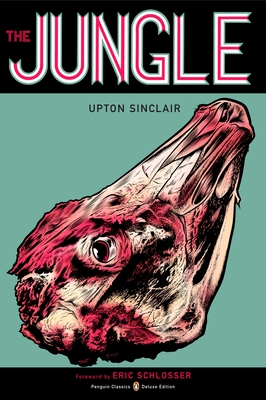

Few American novels have had the policy impact of Upton Sinclair’s Jungle. After the author, in 1904, spent several weeks working incognito in Chicago’s stockyards, he published his exposé. Jack London, invoking another work that changed history, described The Jungle as “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of wage slavery.” What really horrified many readers, however, was not all the bad things that happen to Lithuanian immigrant Jurgis Rudkus and his family after he sustains a work-related injury. Rather, it was their discovery about the meat they were eating.

The novel led to a government inspection of Chicago meat packing plants, which in turn resulted in various sanitation reforms, including the 1906 Meat Inspection Act.

I mention this today because there’s a chance that our rightwing Supreme Court will use a case currently before it (Loper Bright Enterprises v Gina Raimondo) to gut government agencies’ ability to regulate such practices. I owe this awareness to blogger Thom Hartmann, who recently spelled out some of the possible consequences. The justices, he wrote, could destroy the ability of:

— the EPA to regulate pollutants,

— the USDA to keep our food supply safe,

— the FDA to oversee drugs going onto the market,

— OSHA to protect workers,

— the CPSC to keep dangerous toys and consumer products off the market,

— the FTC to regulate monopolies,

— the DOT to come up with highway and automobile safety standards,

— the ATF to regulate guns,

— the Interior Department to regulate drilling and mining on federal lands,

— the Forest Service to protect our woodlands and rivers,

— the FCC to protect us from internet predators,

— and the Department of Labor to protect workers’ rights.

Hartmann then mentions the Jungle:

Far-right conservatives and libertarians have been working for this destruction of agencies — the ultimate in deregulation — ever since the first regulatory agencies came into being with the 1906 creation of the Pure Food and Drugs Act, a response to Upton Sinclair’s bestselling horror story published that year (The Jungle) about American slaughterhouses and meat-packing operations.

Chris Geidner at Law Dork reported that the rightwing justices appear to be champing at the bit to move regulation from the agencies to the judiciary. Neil Gorsuch, son of the woman whom Ronald Reagan hired to gut the clean air act, repeatedly cut off the Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar as he attacked the deference that, since 1984, has been accorded to the agencies. Just as the Supreme Court overturned 50 years of precedent on abortion, so it may overturn 40 years of precedent in the current case.

So imagine going back to a version of the following, as described by Sinclair:

And then there was the condemned meat industry, with its endless horrors. The people of Chicago saw the government inspectors in Packingtown, and they all took that to mean that they were protected from diseased meat; they did not understand that these hundred and sixty-three inspectors had been appointed at the request of the packers, and that they were paid by the United States government to certify that all the diseased meat was kept in the state. They had no authority beyond that; for the inspection of meat to be sold in the city and state the whole force in Packingtown consisted of three henchmen of the local political machine! And shortly afterward one of these, a physician, made the discovery that the carcasses of steers which had been condemned as tubercular by the government inspectors, and which therefore contained ptomaines, which are deadly poisons, were left upon an open platform and carted away to be sold in the city; and so he insisted that these carcasses be treated with an injection of kerosene—and was ordered to resign the same week! So indignant were the packers that they went farther, and compelled the mayor to abolish the whole bureau of inspection; so that since then there has not been even a pretense of any interference with the graft. There was said to be two thousand dollars a week hush money from the tubercular steers alone; and as much again from the hogs which had died of cholera on the trains, and which you might see any day being loaded into boxcars and hauled away to a place called Globe, in Indiana, where they made a fancy grade of lard.

Sinclair relates other horrors by means of worker observations:

Jurgis heard of these things little by little, in the gossip of those who were obliged to perpetrate them. It seemed as if every time you met a person from a new department, you heard of new swindles and new crimes. There was, for instance, a Lithuanian who was a cattle butcher for the plant where Marija had worked, which killed meat for canning only; and to hear this man describe the animals which came to his place would have been worthwhile for a Dante or a Zola. It seemed that they must have agencies all over the country, to hunt out old and crippled and diseased cattle to be canned. There were cattle which had been fed on “whisky-malt,” the refuse of the breweries, and had become what the men called “steerly”—which means covered with boils. It was a nasty job killing these, for when you plunged your knife into them they would burst and splash foul-smelling stuff into your face; and when a man’s sleeves were smeared with blood, and his hands steeped in it, how was he ever to wipe his face, or to clear his eyes so that he could see? It was stuff such as this that made the “embalmed beef” that had killed several times as many United States soldiers as all the bullets of the Spaniards; only the army beef, besides, was not fresh canned, it was old stuff that had been lying for years in the cellars.

And then there are other tainted items, which are all the impoverished Lithuanian family can afford:

When the children were not well at home, Teta Elzbieta would gather herbs and cure them; now she was obliged to go to the drugstore and buy extracts—and how was she to know that they were all adulterated? How could they find out that their tea and coffee, their sugar and flour, had been doctored; that their canned peas had been colored with copper salts, and their fruit jams with aniline dyes? Conservatives and libertarians are always going on about the nanny state, forgetting how many protections we have learned to take for granted. With a rightwing justice in Texas threatening to deprive us to of the abortion pill mifepristone and this Sumpreme Court rulings that wetlands—marshes, swamps, bogs, and other similar areas—are not to be considered “waters” covered by the Clean Water Act—we can see the writing on the wall. Maybe this Supreme Court won’t take us all the way back to 1904 but this is no time for complacency.

Conservatives and libertarians are always going on about the nanny state, forgetting how many protections we have learned to take for granted. With a rightwing justice in Texas threatening to deprive us of the abortion pill mifepristone and this Supreme Court ruling last year that wetlands—marshes, swamps, bogs, and other similar areas—are not to be considered “waters” covered by the Clean Water Act, we can see the writing on the wall. Maybe the Supremes won’t take us all the way back to 1904, but they can still do a lot of damage.