Sometimes, it seems, we have to be deprived of literature to learn how powerful it is and how much we need it. Yesterday a colleague wrote about a former Chinese student of hers who, along with other Young Pioneers, discovered a secret treasure trove of books from the west during the dark days of the Cultural Revolution. Those books helped change her life.

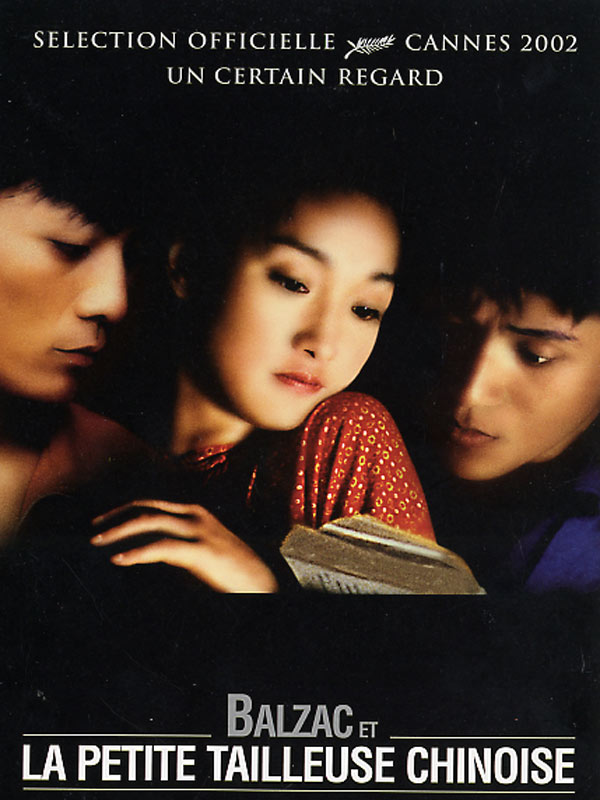

I mentioned that the story reminded me of Dai Sijie’s novel Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, which I recommend highly. (I don’t have a copy before me so I’ll have to rely on memory and a few quotations that I’ve picked up from the internet.) One of the book’s biggest insights is that literature, while powerful, doesn’t always operate as one thinks it will. It can’t be controlled. More on this in a moment.

The book is about two teenagers during the Cultural Revolution, the narrator and his good friend Luo, who are sent to be reeducated in a peasant village.Life there is utterly miserable, but the boys discover that they have resources.One is a knowledge of stories that they can tell the villagers in return for favors.

Their resources are augmented when they discover that another city boy sent there, a former classmate, has a secret trove of books. “Brushing them with the tips of my fingers made me feel as if my pale hands were in touch with human lives,” says the narrator. The books provide them with new plots and images.

They also use the books to win the admiration of a beautiful but illiterate Chinese seamstress. Luo declares, “With these books I shall transform the Little Seamstress. She’ll never be a simple mountain girl again.” And indeed, the books work their magic. At one point the narrator copies down a Balzac passage on the inside of his coat and Luo shares it with her. He reports on the effect:

“After I had read the passage from Balzac to her word for word,” he explained, “she took your coat and reread the whole thing, in silence…. When she’d finished reading she sat there quite still, open-mouthed. Your coat was resting on the flat of her hands, the way a sacred object lies in the palms of the pious.”

The books gain an entrance into the seamstress’s heart. Unfortunately she becomes pregnant, and to gain the secret aid of a doctor, Luo trades a Balzac novel for an abortion. Then the seamstress leaves for the city, informing the boys that “she had learnt one thing from Balzac: that a woman’s beauty is a treasure beyond price.”

Her use of Balzac is ambiguous here. Has she fallen in love with superficial appearance? Does a life as, say, a prostitute loom ahead of her (which, however, still might be a step up from her current existence)? Or has Balzac helped her acknowledge her individuality and fostered a sense of opportunity? As I recall, we aren’t told.

In any event, the boys are desperate and angry and they do precisely what the Maoist regime would do: they burn their books.

Irony builds upon irony in Sijie’s novel, and one of the central ironies is the presence of Balzac. Balzac was a vocal monarchist and Catholic who nevertheless was praised by both Marx and Engels. Marx liked the French novelist’s “profound grasp of real conditions” and Engels said that Balzac depicted

a most wonderfully realistic history of French society … from which, even in economic details (for instance the re-arrangement of real and personal property after the Revolution) I have learned more than from all the professed historians, economists and statisticians of the period together.

Yale professor Peter Brooks explains why they praised Balzac:

Because of his reactionary stance, he was able to perceive all the more sharply the decline of the landed gentry, the coming of the cash nexus and the end of what he nostalgically saw as an ordered, organic society with each person in an assigned role. The new era was one of convulsive egotism, the cult of the individual personality. His fictional philosopher, Louis Lambert, before sinking into sullen madness, formulates a ”law of disorganization” that characterizes the new society. As Pére Goriot raves on his deathbed, nothing matters anymore but money: money will buy you anything, even your unfaithful daughters.

Seen from this perspective, then, the very world that Balzac is condemning becomes intoxicating to the little seamstress. For that matter, this world has captured the imagination of modern China. I saw this first hand a few years ago when our college was visited by a Chinese business delegation and all I heard was talk of real estate and automobiles and new appliances.

The seamstress being drawn to Balzac is a little like the way people in marketing (so my son informs me from his experience in a Baltimore firm) glamorize the life lived by the advertising executives in the HBO series Mad Men. While some watching Mad Men might see the emptiness of lives lived in quiet (and sometimes not so quiet) desperation, others see martinis and beautiful suits and fast cars.

I suppose one could make an elaborate case that the energetic but heartless world that Balzac depicted was an advance over paternal monarchy. Certainly that’s how Marx and Engels saw the situation. In fact, they thought that a capitalist revolution needed to precede a proletariat revolution, and some Marxists have argued that the Russian and Chinese communist revolutions were bound to fail (Marx would have been horrified by the Chinese cultural revolution) because they skipped the bourgeois stage.

Whatever the case, the idea of introducing Balzac to the little seamstress works at first for the boys and then backfires. The narrator and Luo are sustained by the books that come into their lives. But even as the books liberate them, they also liberate someone they would like to control. No wonder totalitarian regimes don’t like such books.

Added note: Years ago I had a faculty member from the University of Fudan (in Shanghai) take a composition class from me and recount how she had been shipped into the country during the Cultural Revolution. The first night there, she said, all the women were housed in a large warehouse that had just been emptied of its chemical fertilizers. She remembers that, that evening, one of the women started to cry and her wailing spread like a contagion through them all.

She also talked about picking up French lessons on a wireless they had and spoke of her frustration when the lessons went only so far before circling around again to beginner level. Nevertheless, she emerged from the ordeal without bitterness and was one of the most upbeat (and one of the smartest) people I have encountered.

2 Trackbacks

[…] Seductive Balzac in Communist China […]

[…] Seductive Balzac in Communist China […]