Monday

Today I grapple with a children’s classic that I loved as a child but that I have essentially “canceled”—by which I mean, I do not read it to my grandchildren. Many on the right would accuse me of being “woke” as I grapple with Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo, so this essay gives me the opportunity to address their attacks as well as grapple with my own conflicted feelings.

Productive cancel conversations can only occur with people who enter them in good faith, and few of those complaining right-wingers appear interested in good faith. For them, cancel culture is just a stick with which to beat up the left, not to explore ideas. This becomes clear when we see how readily they cancel anyone who doesn’t agree with them, from the Dixie Chicks to San Francisco quarterback Colin Kaepernick to any Republican who does not back Donald Trump 100% (including Mike Pence and Liz Cheney). They aren’t interested in free speech for everyone, just free speech for themselves. The Editorial Board’s John Stoehr lays out the problem in a mantra he shares with his political science students:

“You can’t get anything done when fascists are sitting at the table of democratic politics.” A democratic community can tolerate a vast array of opinions. However, it cannot, and should not, tolerate opinions in which democratic politics is the problem. If it does, then nothing needing to get done gets done—and everyone suffers.

So having established that, here’s the thinking behind my painful decision not to read Little Black Sambo to my grandchildren.

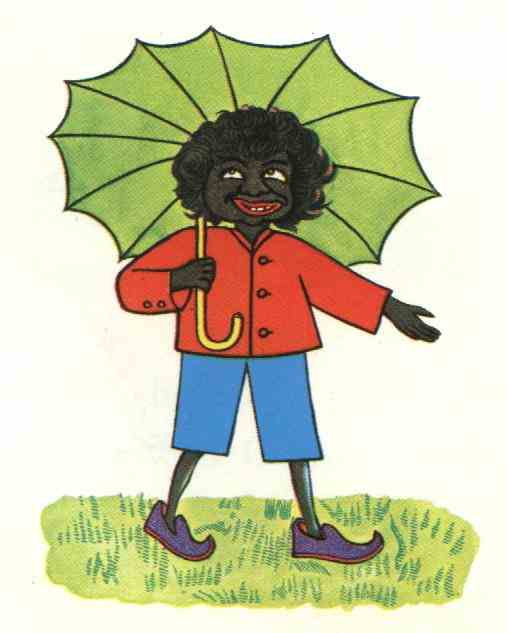

It’s painful because I absolutely loved this story as a child and loved reading it to my own children. The protagonist is an Indian boy, son of Black Mumbo and Black Jumbo, who gets a new outfit, complete with green umbrella and “purple shoes with crimson soles and crimson linings.” (I don’t have to return to the book since I still have it memorized.) While out proudly walking in his new attire, he is accosted for four successive tigers, each of whom says, “Little Black Sambo, I’m going to eat you up.” In each case, Sambo barters for his freedom with one of his new items. When complications arise—how can a tiger carry an umbrella? what use are two shoes to a four-footed animal?—Sambo ingeniously figures out solutions. (“You can use your tail.” “You can wear them on your ears.”) Following the bargain, each tiger strides off declaring, “Now I’m the grandest tiger in the jungle.”

While his life has been spared, however, Sambo has been stripped of his finery and cries bitterly. Fortunately for him, the four tigers fall to fighting with each other over who is the grandest. Each grabs the tail of another and they whirl around a tree so quickly that they churn themselves into butter (“or ghi, as it is called in India”). Sambo dons the clothes they have cast aside prior to their fight, and Black Jumbo, coming across the ghi, gathers it up. The book concludes with pancakes for dinner:

So [Black Mumbo] got flour and eggs and milk and sugar and butter, and she made a huge big plate of most lovely pancakes. And she fried them in the melted butter which the Tigers had made, and they were just as yellow and brown as little Tigers.

And then they all sat down to supper. And Black Mumbo ate Twenty-seven pancakes, and Black Jumbo ate Fifty-five, but Little Black Sambo ate a Hundred and Sixty-nine, because he was so hungry.

There’s a complicated psychological drama concerning autonomy and identity going on here. The child in new clothes steps out into the world confidently, only to discover that there are forces that will negate this new-found assertiveness. The threat of “eat you up” is heard by children as sending them back as undifferentiated members of the family unit (and of the parents) with no independent self. In each case, however, Sambo problem-solves his way out of difficulty, proving that he is in fact his own person. The story ends in a revenge fantasy where the forces that threatened to negate his individuality themselves become undifferentiated and the prey becomes predator. The pancakes are “just as yellow and brown as little Tigers.”

The book was fun to read to my kids. “Little Black Sambo, I’m going to eat you up,” I would growl to Justin, Darien and Toby, and they would squeal in delighted terror as I hugged them—which is to say, as I symbolically swallowed them up, denying them their autonomy—but in a way that reassured them that all was well. In other words, they experienced their anxiety as a game, one which they knew would conclude with a happy ending.

Freud described the process in Beyond the Pleasure Principle after observing a nephew in a crib playing a “fort-da” (away-here) game with a spool attached to a string. The nephew would throw the spool out of sight while calling out “fort” and then bring it back while saying “da.” Freud interpreted this as him playing out abandonment anxieties, the most primal of all fears. The disappearing spool was his mother leaving, and by turning it into a game, the child was reassuring himself that he was not helpless but had symbolic mastery over this most frightening of events.

Elsewhere Freud says that stories are more complicated versions of this mastering anxiety drama. In his essay “Creative Writers and Daydreaming,” Freud writes that, when we grow up, we turn to daydreams, which authors transform into literature:

As people grow up, then, they cease to play, and they seem to give up the yield of pleasure which they gained from playing. But whoever understands the human mind knows that hardly anything is harder for a man than to give up a pleasure when he has once experienced. Actually, we can never give anything up; we only exchange one thing for another. What appears to be a renunciation is really the formation of a substitute or surrogate. In the same way, the growing child, when he stops playing, gives up nothing but the link with real objects: instead of playing, he now phantasies. He builds castles in the air and creates what are called daydreams. I believe that most people construct phantasies at times in their lives. This is a fact which has long been overlooked and whose importance has therefore not been sufficiently appreciated.

Little Black Sambo is a child’s level fantasy, powerful in that it deals with core identity issues but elementary. We demand more complicated stories when we get older.

So why am I not reading it to my grandchildren. The reasons are mainly cultural.

First, the book recalls the pickaninny image from America’s slave and Jim Crow eras. Second, Sambo too is a diminutive caricature for mixed race people of those times. Finally, the emphasis on the color of Sambo’s skin draws special attention to a colonialist distinction. We see Bannerman, an English woman living in India, focusing on the way Indians differ from her.

My daughter-in-law Candice, who is from Trinidad, told me that she grew up not thinking about skin color because pretty much everyone around her looked like her. Only when she came to the United States did she come to think of herself as a woman of color. It doesn’t matter that Bannerman is not judgmental in her use of the world “Black.” What comes through is her colonialist perspective.

I understand that a 1996 version of the book has authentic Indian names and has been retitled The Story of Little Babaj (his parents now are Mamaji and Papaji). That addresses some of my issues. Yet I can’t get out of my head this English woman marveling at the (from her reserved English perspective) gaudy displays of the colonized (“red shoes with crimson soles and crimson linings!”) Exoticizing the other is still going on.

Or not. I acknowledge this may be a gray area and that I may be overly sensitive. I’m willing to have difficult conversations about the matter. But only with people who are interested in genuine dialogue rather than in wielding ideological cudgels. Only those truly concerned that our children grow up with open minds and a healthy sense of self-respect will I take seriously.