Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951 at gmail dot com and I will send it/them to you. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

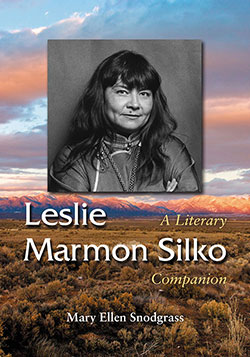

The apocalyptic future that Laguna Pueblo novelist Leslie Marmon Silko predicted for Arizona in 1991 is coming to pass. Actually, Silko makes a lot of dire predictions in her dystopian novel Almanac of the Dead, and some are closer to being actualized in 2023 than others. And perhaps it doesn’t take a genius writer like Silko to foretell that the state would one day have water problems.

The particular development I have in mind involves Scottsdale, located on the outskirts of Phoenix, cutting off water to some of its border communities. As the Washington Post reported,

On Jan. 1, the city of Scottsdale, which gets the majority of its water from the Colorado River, cut off Rio Verde Foothills from the municipal water supply that it has relied on for decades. The result is a disorienting and frightening lack of certainty about how residents will find enough water as their tanks run down in coming weeks, with a bitter political feud impacting possible solutions.

The reason: A historic drought has led to shrinking reservoirs and “unprecedented restrictions in usage of the Colorado River.”

Oblivious to such a future, however, for decades residents have been gobbling up land in the Sonora Desert, leading poet Richard Shelton to lament (in “Requiem for Sonora”),

men are coming inland to you

soon they will make you the last resort

for tourists who have

nowhere else to go

what will become of the coyote

with eyes of topaz

moving silently to his undoing

the ocotillo

flagellant of the wind

the deer climbing with dignity

further into the mountains

the huge delicate saguarowhat will become of those who cannot learn

the terrible knowledge of cities

In Silko’s novel, Tucson has a particularly irresponsible realtor who dreams of constructing a green oasis in the desert. She will call it Venice and wants it to have the Italian city’s water associations, with canals, fountains, and lush golf courses. She pooh-poohs the idea of having special desert golf courses

No deserts in Venice, Arizona, not for an instant, and certainly not for eighteen holes of golf. Tucson had enough desert. It was ridiculous for longtime residents to try to pretend Tucson wasn’t any different from Phoenix or Orange county. People wanted to have water around them in the desert. People felt more confident and carefree when they could see water spewing out around them.

And in fact, desert golf courses don’t sit well with out-of-state visitors:

Even the celebrity golfers [Senator Max Blue] had brought around had been too tense and nervous to play well. The desert was too close for most of the Californians and New Yorkers. Texans could not swing their irons for fear of rattlers they imagined coiled on the fairway.

Leah, meanwhile, parrots what is a fairly common refrain for many in her profession:

Tell me they are using up all the water and I say: don’t worry. Because science will solve the water problem of the West. New technology. They’ll have to.”

In other words, it’s someone else’s problem.

Leah’s water ideas help her compete with giant home-building corporations that are pushing luxury communities. The novel explains that her “water gimmick”

had really worked in Scottsdale and Tempe. A scattering of pisspot fountains and cesspool lakes evoked memories of Missouri or New York or wherever the dumb shits had come from. Leah wanted Venice to live up to it name. She planned each detail carefully. No synthetic marble in the fountains. Market research had repeatedly found new arrivals in the desert were reassured by the splash of water. They are in the real estate business to make profits, not to save wildlife or save the desert. It was too late for the desert around Tucson anyway. Look at it. Pollution was already killing foothill paloverde trees all across the valley.

Leah’s elaborate plans involve purchasing deep-well rigs on the cheap from bankrupt Texas old-fields and tapping into the aquafer. Unfortunately for her, even with these rigs she can only get salt water. Still, being a realtor, she has a way of spinning setbacks:

Leah had not worried. If the canals and lakes of Venice, Arizona, ran with salter water that lent authenticity; salter water could be used to flush toilets. For drinking water, Leah would provide bottled glacier water from the Colorado Rockies.

In Silko’s dystopian future, however, the real estate market eventually collapses and Arizona depopulates and goes into bankruptcy. Nor is that all that goes wrong in the area. There are unstoppable mass migrations of Indian descendants moving northward, prepared to reclaim the land that the Whites took from them centuries ago. (Silko sees the 500 years of White domination as only a blip in the Indian timeline.) In Mexico, meanwhile, extreme income inequality has led to gated communities, which hire private armies to defend them against gangs while the country itself descends into civil war. In addition, America also has anarchistic hackers planning to take down its power grid. Whee!

But back to Arizona’s water troubles. In my recent visit to the Sonora, I saw only too clearly the reasons for Shelton’s despair. “Oh my desert,” he concludes in “Requiem to Sonora,” “yours is the only death I cannot bear.”