Just as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight supported me as I grieved for my son, so is it supporting me now as I interact with a close friend, a philosophy professor, who has been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

Just as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight supported me as I grieved for my son, so is it supporting me now as I interact with a close friend, a philosophy professor, who has been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

Alan’s tumors began in his neck and eyelid and have now migrated down to his lungs. A small (but temporary) blessing is that they are currently at the margins of the lungs and are not blocking passage. Last fall doctors thought he would be dead by this spring, and while that has not happened—he is doing well at the moment, including working out daily at the gym—the tumors continue to grow. He has always eaten healthily and given himself over to the beauty of nature and art, so maybe that is why the cancer hasn’t exploded like the doctors predicted. We both find ourselves grabbing onto any consoling signs, even though, by any objective measurement, the outlook is grim.

As I talk to Alan, I often think of us in terms of the images in SGGK and tell Alan about them. Sometimes we are like Gawain partying at Camelot, as though we haven’t just heard a death sentence pronounced. Or we try to be like Gawain who, prior to embarking on his journey, “smile[s] with tranquil eye” and says, with apparent philosophic or stoic resolve, “In destinies sad or merry,/True men can but try.”

I also see Alan looking at life with new intensity. In Part II of SGGK, the poet describes the year as it unfolds following the encounter with the Green Knight—through Lent, spring, summer, and fall, all the way up to September 29, Michaelmas, when Gawain girds himself to ride out and find the Green Chapel. The description captures the poignancy of seeing each season for possibly the last time. Alan talks about the seasons this way. Here is the poem’s beautiful description of spring:

But then the world’s weather with winter contends:

The keen cold lessens, the low clouds lift;

Fresh falls the rain in fostering showers

On the face of the fields; flowers appear.

The ground and the groves wear gowns of green;

Birds build their nests, and blithely sing

That solace of all sorrow with summer comes

ere long.

And blossoms day by day

Bloom rich and rife in throng;

Then every grove so gay

Of the greenwood rings with song

As I watch Alan wrestle with each decision regarding his cancer, I think of the hunted animals in the poem.Radiation or not?Chemotherapy or not?(He decides yes for the radiation, no for the chemo.)The animals represent different responses to death: there is the deer’s willed ignorance, the boar’s determination to fight, the fox’s darting and dodging.Alan is each of these animals at one time or another and so are we his friends as we watch him.If the cancer evolves as it might—I still find myself needing to say “if” and “might”—then we will all be confronting up close the vivid signs of death as it takes over Alan’s body.The poet doesn’t mince words as he describes death.Here’s a passage of the hunters dressing the deer, which my mind wanders to as a sobering reality check.I am struck by how the poem, which sees death as a natural part of life, presents matter-of-factly even the most gruesome details:

Then they slit the slot open and searched out the paunch,

Trimmed it with trencher-knives and tied it up tight.

They flayed the fair hide from the legs and trunk,

Then broke open the belly and laid bare the bowels,

Deftly detaching and drawing them forth.

And next at the neck they neatly parted

The weasand from the windpipe, and cast away the guts.

I have found, in my talks with Alan, that the image of Gawain lost in the forest is one of the most powerful images we have. We try to soldier on, handling our duties as they arise, but feel ourselves more and more lost. This image of being lost in the wilderness is a much-used literary symbol of existential confusion. I think of Dante’s dark wood and the forests in The Scarlet Letter and Deliverance. The images comfort because they give our inner turmoil a concrete feel. We sense that we see what we are up against. We feel that someone out there understands what we are going through.

At least Alan is not handling his cancer the way another colleague of mine did years ago—using work, including participating on faculty committees to the very end, as a way to avoid thinking about his disease.And in the process, becoming more and more angry and closed in on himself.Although maybe this individual, whom I didn’t know well, shifted in his last days, just as Gawain finally finds himself feeling so lost that he opens up and prays for help.

Alan, on the other hand, inspires me by his determination to make every moment count: he listens to music, takes walks in nature, seeks out old friends, continues to read and to watch films, researches new topics, and participates in an every-other-week salon that his colleagues have begun holding in his honor (where we talk about such issues as beauty, dreams, God, and the like).Perhaps it is because he sees himself as going through a journey to discover what it all means (and we his friends are going through a similar quest as we wrestle with our own response to his cancer), that he seems to have a framework for grappling with the down moments.

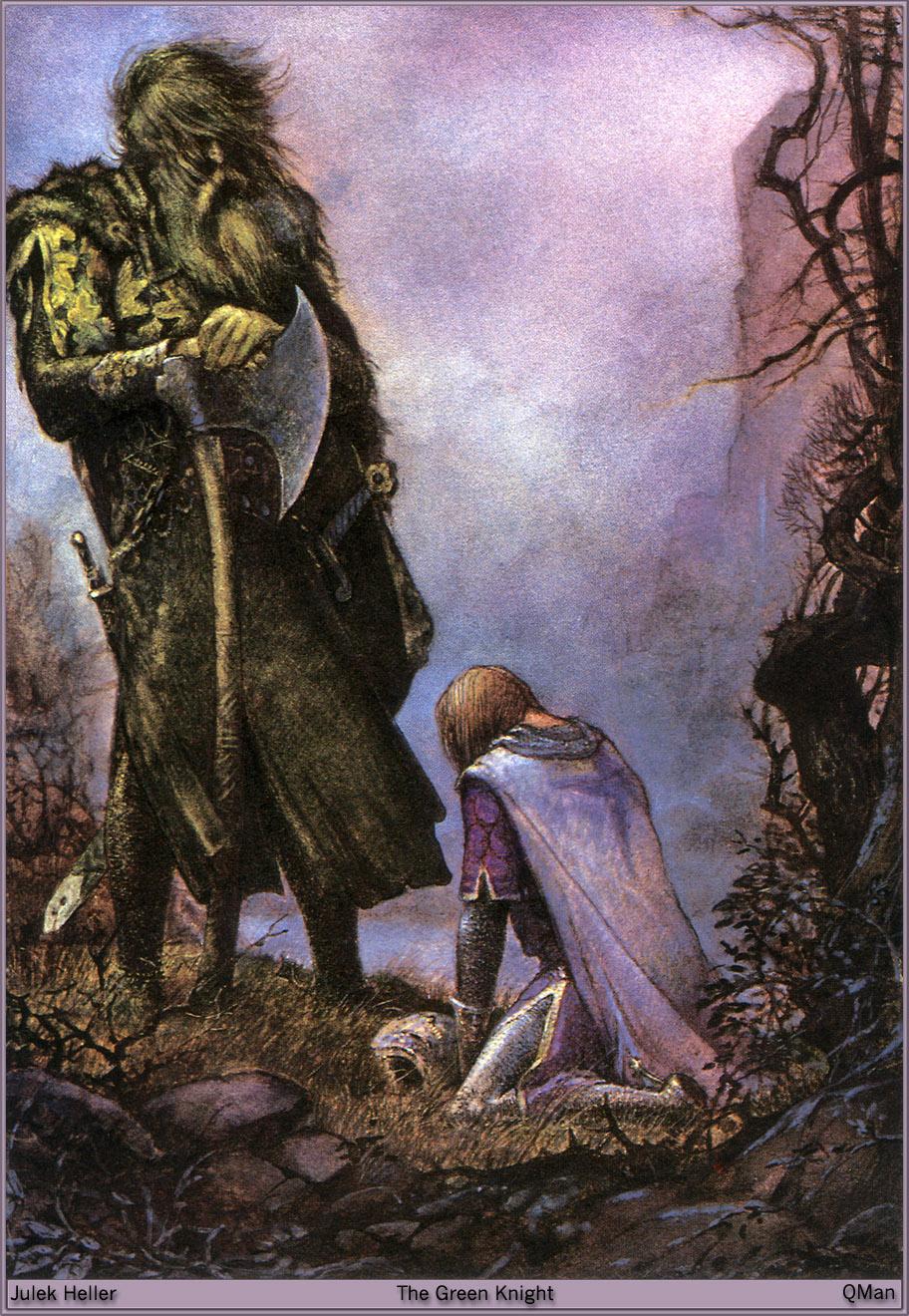

What does this framework provide? For me it means that, when I see graphic reminders of death, I strive not to flinch or shy away. It means that, when life reaches out to me in all her sensuality, I try to step forward and take her hand. It means that when death, like the Green Knight, plays games with Alan, alternating between good and bad news (is death merely feinting with his axe or is it for real this time?), I try to open myself to whatever it has in store. I did this as I grappled with the pain of my son’s death and I’m doing it now as I reach out to Alan. Neither Alan nor I have reached a point where we can gaze down serenely on death. “Black dreams” still “darkly mutter,” as they do for Gawain. The approaching darkness still periodically tears us up. But at least we can regard our responses as a very human, and at the same time a very heroic, struggle. Imagining us embarked on a heroic quest helps make the ordeal more bearable for me.

If that isn’t a strong argument for continuing to read literature, I don’t know what is.

One Trackback

[…] I’ve written in the past about how the Arthurian romance, written by an author who might have had been alive in 1350 when the black plague was killing a third of Europe, is a remarkably healthy exploration of how humans should handle death. As I interpret it, the poem shows us that, because of our fear of death, we close ourselves to life. The Green Knight is trying to convey to Gawain that the more open he is to death, the richer his living will be. […]