Wednesday

I am lecturing at the University of Ljubljana today on James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues,” which ranks among my favorite short stories. I will be lecturing for an American Ethnic Literature class, which takes me back to 1987-88, when I taught just such a class (including this story) in the same building as a Fulbright lecturer. Perhaps I will teach in the same classroom.

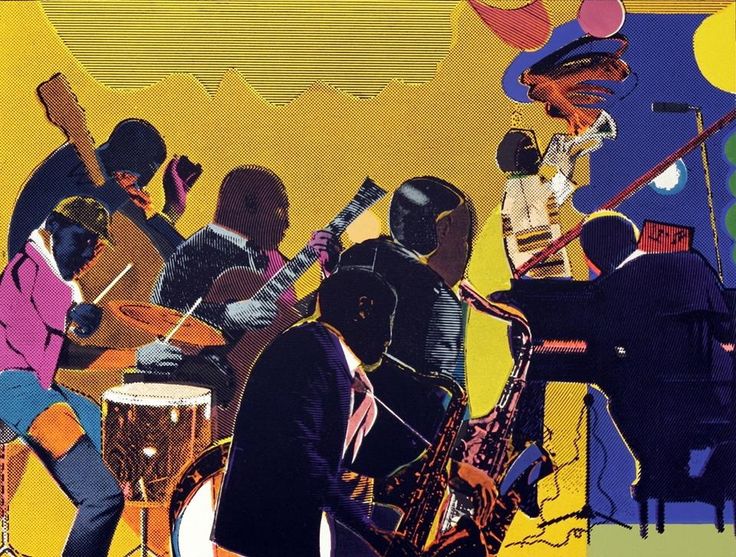

I’m focusing on “The Blues as African-American Resistance,” which means that I will focus on how music wars with entrapment and darkness. The blues appear to be engaging in a rearguard action as Baldwin explores art’s liberating potential.

The story begins with news of Sonny’s imprisonment for a heroine-related crime. The narrator, his older brother, is a high school algebra teacher who thinks that one advances by will power and hard work. Baldwin makes clear he has much to learn.

Throughout the story, we hear Harlem described as a trap from which one never entirely escapes:

So we drove along, between the green of the park and the stony, lifeless elegance of hotels and apartment buildings, toward the vivid, killing streets of our childhood. These streets hadn’t changed, though housing projects jutted up out of them now like rocks in the middle of a boiling sea…[H]ouses exactly like the houses of our past yet dominated the landscape, boys exactly like the boys we once had been found themselves smothering in these houses, came down into the streets for light and air and found themselves encircled by disaster. Some escaped the trap, most didn’t. Those who got out always left something of themselves behind, as some animals amputate a leg and leave it in the trap. It might be said, perhaps, that I had escaped, after all, I was a school teacher; or that Sonny had, he hadn’t lived in Harlem for years. Yet, as the cab moved uptown through streets which seemed, with a rush, to darken with dark people, and as I covertly studied Sonny’s face, it came to me that what we both were seeking through our separate cab windows was that part of ourselves which had been left behind. It’s always at the hour of trouble and confrontation that the missing member aches.

The narrator talks about the darkness without and the darkness within. One can do only so much about the darkness without, especially if one is African American. When the uncle of the narrator and Sonny is mowed down by white boys messing around, the two darknesses become one and the same. As the mother reports,

Your Daddy was like a crazy man that night and for many a night thereafter. He says he never in his life seen anything as dark as that road after the lights of that car had gone away.

Sonny describes his heroine-world as a dark cage in which he is locked:

I was all by myself at the bottom of something, stinking and sweating and crying and shaking, and I smelled it, you know? my stink, and I thought I’d die if I couldn’t get away from it and yet, all the same, I knew that everything I was doing was just locking me in with it.

Another image of entrapment, this one particularly painful, is the narrator’s two-year-old daughter trapped in a polio-stricken body:

[Isabel] heard Grace fall down in the living room. When you have a lot of children you don’t always start running when one of them falls, unless they start screaming or something. And, this time, Gracie was quiet. Yet, Isabel says that when she heard that thump and then that silence, something happened to her to make her afraid. And she ran to the living room and there was little Grace on the floor, all twisted up, and the reason she hadn’t screamed was that she couldn’t get her breath. And when she did scream, it was the worst sound, Isabel says, that she’d ever heard in all her life, and she still hears it sometimes in her dreams. Isabel will sometimes wake me up with a low, moaning, strangling sound and I have to be quick to awaken her and hold her to me and where Isabel is weeping against me seems a mortal wound.

The scream represents our need, within the depth of our pain, for some kind of expression. The story, then, is how to turn that scream into music. This is the meaning of Sonny’s blues.

Only after his daughter dies does the narrator reach out to his imprisoned younger brother. Locked in his own suffering, he finally understands what Sonny endures. At the end of the story, he learns that Sonny has a special gift for those who suffer.

Throughout the story, we see people converting their suffering into music. For instance, at one point we watch a group of Christian street musicians performing:

“‘Tis the old ship of Zion,” they sang, and the sister with the tambourine kept a steady, jangling beat, “it has rescued many a thousand!” Not a soul under the sound of their voices was hearing this song for the first time, not one of them had been rescued. Nor had they seen much in the way of rescue work being done around them. Neither did they especially believe in the holiness of the three sisters and the brother, they knew too much about them, knew where they lived, and how. The woman with the tambourine, whose voice dominated the air, whose face was bright with joy, was divided by very little from the woman who stood watching her, a cigarette between her heavy, chapped lips, her hair a cuckoo’s nest, her face scarred and swollen from many beatings, and her black eyes glittering like coal. Perhaps they both knew this, which was why, when, as rarely, they addressed each other, they addressed each other as Sister. As the singing filled the air the watching, listening faces underwent a change, the eyes focusing on something within; the music seemed to soothe a poison out of them; and time seemed, nearly, to fall away from the sullen, belligerent, battered faces, as though they were fleeing back to their first condition, while dreaming of their last.

Looking down on the performing musicians, Sonny remarks,

All that hatred down there, all that hatred and misery and love. It’s a wonder it doesn’t blow the avenue apart.

When the narrator finally hears his brother perform, he learns that one can escape, if only for a moment, from the darknesses:

I seemed to hear with what burning he had made [the music] his, and what burning we had yet to make it ours, how we could cease lamenting. Freedom lurked around us and I understood, at last, that he could help us to be free if we would listen, that he would never be free until we did.

The narrator finds himself reliving his parents’ suffering, his wife’s suffering, and his own:

Yet, there was no battle in his face now, I heard what he had gone through, and would continue to go through until he came to rest in earth. He had made it his: that long line, of which we knew only Mama and Daddy. And he was giving it back, as everything must be given back, so that, passing through death, it can live forever. I saw my mother’s face again, and felt, for the first time, how the stones of the road she had walked on must have bruised her feet. I saw the moonlit road where my father’s brother died. And it brought something else back to me, and carried me past it, I saw my little girl again and felt Isabel’s tears again, and I felt my own tears begin to rise. And I was yet aware that this was only a moment, that the world waited outside, as hungry as a tiger, and that trouble stretched above us, longer than the sky.

Sonny is a Christ figure who takes the world’s suffering upon his shoulders, and the story ends with a fabulous image from the Book of Isaiah. The narrator orders Sonny a scotch and milk, and as he plays it sits above him on the piano, glowing and shaking “like the very cup of trembling.” This is the cup of suffering that God promises he will remove from the people of Israel.

For at least a moment, the cup has been lifted.