Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Monday

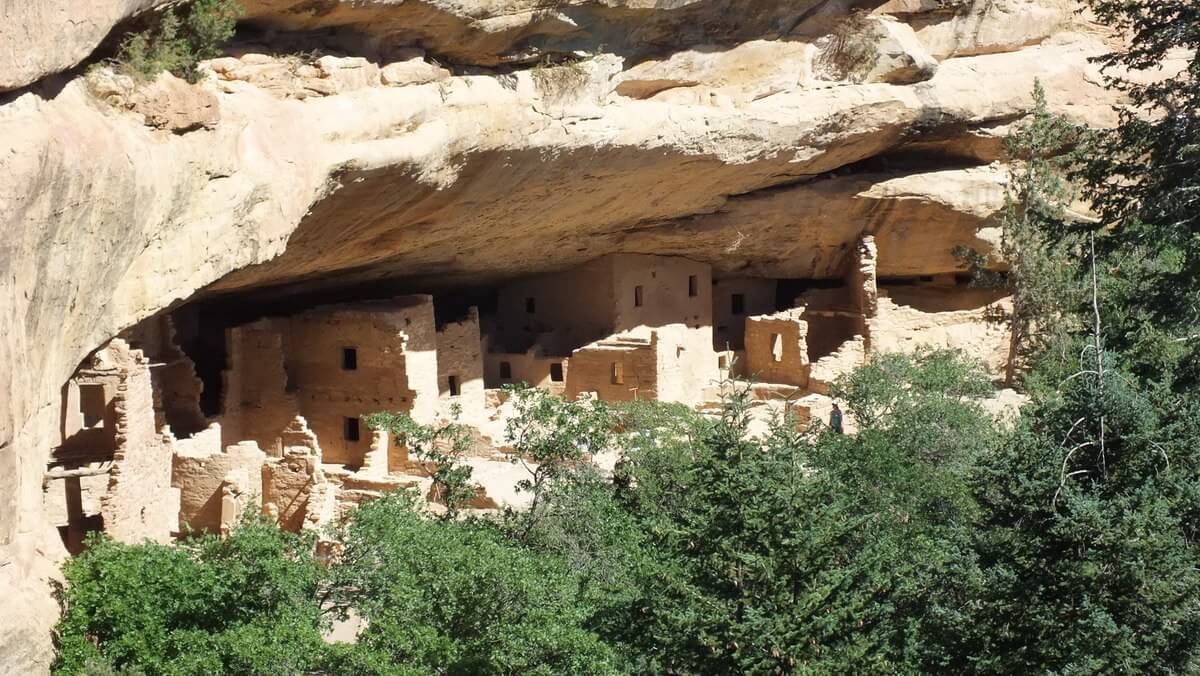

Julia and I are currently vacationing in New Mexico, in part because of a novel I read many years ago. Willa Cather describes ancient Pueblo cliff dwellings in The Professor’s House, and her description so captivated me that I resolved that one day we would go out to visit them. And now we have.

To be sure, Cather is describing Blue Mesa in Mesa Verde National Park whereas we visited two smaller sites, Puye and Bandolier. We fell in love with Puye for its intimacy and for our guide, Emeric Padilla, a member of the Santa Clara tribe. As such, he is a descendant of the original inhabitants.

Humbler though the site may be, we were nevertheless awed as Cather’s character Tom Outland is awed when he discovers Blue Mesa:

In stopping to take breath, I happened to glance up at the canyon wall. I wish I could tell you what I saw there, just as I saw it, on that first morning, through a veil of lightly falling snow. Far up above me, a thousand feet or so, set in a great cavern in the face of the cliff, I saw a little city of stone, asleep. It was as still as sculpture–and something like that. It all hung together, seemed to have a kind of composition: pale little houses of stone nestling close to one another, perched on top of each other, with flat roofs, narrow windows, straight walls, and in the middle of the group, a round tower.

We had another experience similar to Outland’s, which is that, once one has seen one cluster of stone houses, one can’t help but see hundreds of others—or if not houses, at least the marks in the cliffs where the wooden house beams were once embedded. When we drove from Puye to Bandolier, it seemed that every other cliff face we scanned had the telltale marks. We were witnessing what had once been high density two- and three-story condominiums:

When I at last turned away, I saw still another canyon branching out of this one, and in its wall still another arch, with another group of buildings. The notion struck me like a rifle ball that this mesa had once been like a beehive; it was full of little cliff-hung villages, it had been the home of a powerful tribe, a particular civilization.

Outland notes that immense care was taken in construction, and our guide, who had once done stonework in Santa Fe, agreed, explaining how the load-bearing walls had to be carefully calibrated in order to support a second and sometimes third story. Here’s Outland again:

One thing we knew about these people; they hadn’t built their town in a hurry. Everything proved their patience and deliberation. The cedar joists had been felled with stone axes and rubbed smooth with sand. The little poles that lay across them and held up the clay floor of the chamber above, were smoothly polished. The door lintels were carefully fitted (the doors were stone slabs held in place by wooden bars fitted into hasps). The clay dressing that covered the stone walls was tinted, and some of the chambers were frescoed in geometrical patterns, one color laid on another. In one room was a painted border, little tents, like Indian tepees, in brilliant red.

The views, both from the village atop the mesa and from the homes that had been built into its side, were spectacular. Padilla pointed out that this was ideal from a protection point of view, pointing out that we could see for miles when we looked down. Outland notes,

But the really splendid thing about our city, the thing that made it delightful to work there, and must have made it delightful to live there, was the setting. The town hung like a bird’s nest in the cliff, looking off into the box canyon below, and beyond into the wide valley we called Cow Canyon, facing an ocean of clear air. A people who had the hardihood to build there, and who lived day after day looking down upon such grandeur, who came and went by those hazardous trails, must have been, as we often told each other, a fine people.

Padilla tolds us that the Pueblo probably lived in the village atop the mesa in the summer and in the cliff dwellings in the winter. The caves they dug out of the rock, he noted, would have provided extra warmth, and, as they faced west, they also benefited from the afternoon sun.

After marveling at the village, Outland then asks the big question: “But what had become of them? What catastrophe had overwhelmed them?”

Our guide speculates that drought forced his own Pueblo tribe off the mesa and closer to the Rio Grande below, which while more fertile also made the tribes more vulnerable to attacks from Navajo, Apache, and Comanche raiders and ultimately from the Spanish.

In Professor’s House, wonder is followed by betrayal. Outland goes to Washington to see if he can interest the Smithsonian in an archaeological expedition and, when he returns, he finds that his partner has sold off many of the relics to German tourists. When, defending himself, his partner “reminded me about how we used to talk of getting big money from the Government,” Outland explodes:

I admitted I’d hoped we’d be paid for our work, and maybe get a bonus of some kind, for our discovery. But I never thought of selling them, because they weren’t mine to sell–nor yours! They belonged to this country, to the State, and to all the people. They belonged to boys like you and me, that have no other ancestors to inherit from. You’ve gone and sold them to a country that’s got plenty of relics of its own. You’ve gone and sold your country’s secrets…”

In Puye’s case, that sense of ownership has finally been settled. Everything found there belongs to the Santa Clara Pueblo, who either preserve it or leave it lying around. Padilla, who is constantly finding arrowheads, axe fragments, pottery shards, ornament fragments, and other items, has little piles scattered around the ruins, some of which he covers with a rock and others which he simply sets out for all to see. One rich source of artifacts, he pointed out to us, are anthills since the ants will surface items that have been buried. Looking down at one such hill, he picked up a small fragment of turquoise, which would have been conveyed into the area by traders. Any fragments we found we gave to Padilla.

Rereading the passages from Professor’s House, I felt sorry for Outland that he didn’t have such a guide to take him around and to tell him how Indians have never entirely abandoned the sites, even though they no longer live there. Padilla played there when a child and was well versed in the various pathways to the top of the mesa.

Even though Cather’s explorer lacks modern archaeological knowledge, however, he describes a spiritual connection with the mesa that I sensed Padilla has as well. When Outland returns alone after his unsuccessful trip to Washington, he reconnects at a deep level. He doesn’t even have to enter the abandoned ruins to do, contenting himself with just looking up:

The moon was up, though the sun hadn’t set, and it had that glittering silveriness the early stars have in high altitudes. The heavenly bodies look so much more remote from the bottom of a deep canyon than they do from the level. The climb of the walls helps out the eye, somehow. I lay down on a solitary rock that was like an island in the bottom of the valley, and looked up. The grey sage-brush and the blue-grey rock around me were already in shadow, but high above me the canyon walls were dyed flame-color with the sunset, and the Cliff City lay in a gold haze against its dark cavern. In a few minutes it, too, was grey, and only the rim rock at the top held the red light. When that was gone, I could still see the copper glow in the piñons along the edge of the top ledges. The arc of sky over the canyon was silvery blue, with its pale yellow moon, and presently stars shivered into it, like crystals dropped into perfectly clear water.

Outland reflects on what it all means:

I remember these things, because, in a sense, that was the first night I was ever really on the mesa at all–the first night that all of me was there. This was the first time I ever saw it as a whole. It all came together in my understanding, as a series of experiments do when you begin to see where they are leading. Something had happened in me that made it possible for me to co-ordinate and simplify, and that process, going on in my mind, brought with it great happiness. It was possession. The excitement of my first discovery was a very pale feeling compared to this one. For me the mesa was no longer an adventure, but a religious emotion. I had read of filial piety in the Latin poets, and I knew that was what I felt for this place. It had formerly been mixed up with other motives; but now that they were gone, I had my happiness unalloyed.

And finally:

I can scarcely hope that life will give me another summer like that one. It was my high tide. Every morning, when the sun’s rays first hit the mesa top, while the rest of the world was in shadow, I wakened with the feeling that I had found everything, instead of having lost everything. Nothing tired me. Up there alone, a close neighbor to the sun, I seemed to get the solar energy in some direct way. And at night, when I watched it drop down behind the edge of the plain below me, I used to feel that I couldn’t have borne another hour of that consuming light, that I was full to the brim, and needed dark and sleep.

Looking up at the steep cliff with their little hollows, I too felt a part of something bigger.